When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

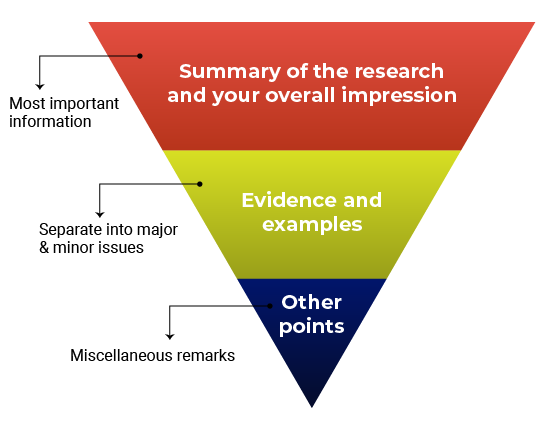

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

* E-mail: [email protected]

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Collection date 2013 Jul.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

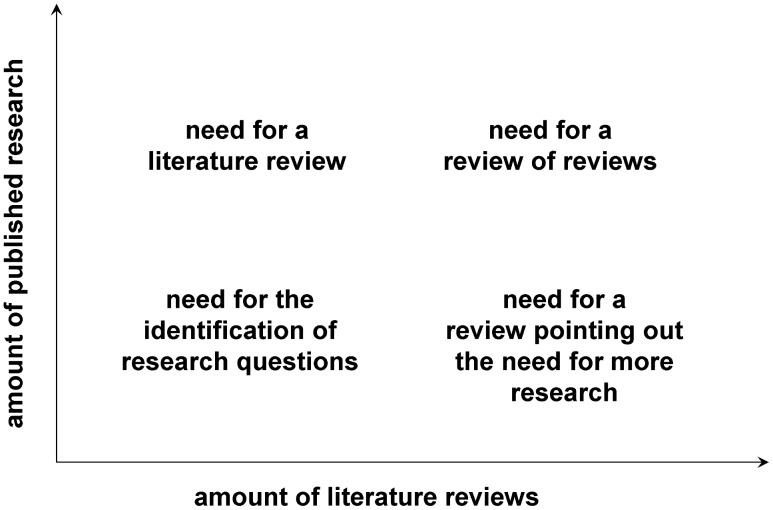

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

Figure 1. A conceptual diagram of the need for different types of literature reviews depending on the amount of published research papers and literature reviews.

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

be thorough,

use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

the major achievements in the reviewed field,

the main areas of debate, and

the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Rapple C (2011) The role of the critical review article in alleviating information overload. Annual Reviews White Paper. Available: http://www.annualreviews.org/userimages/ContentEditor/1300384004941/Annual_Reviews_WhitePaper_Web_2011.pdf . Accessed May 2013.

- 2. Pautasso M (2010) Worsening file-drawer problem in the abstracts of natural, medical and social science databases. Scientometrics 85: 193–202 doi: 10.1007/s11192-010-0233-5 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Erren TC, Cullen P, Erren M (2009) How to surf today's information tsunami: on the craft of effective reading. Med Hypotheses 73: 278–279 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.05.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Hampton SE, Parker JN (2011) Collaboration and productivity in scientific synthesis. Bioscience 61: 900–910 doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.11.9 [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Ketcham CM, Crawford JM (2007) The impact of review articles. Lab Invest 87: 1174–1185 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700688 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34: 3–15 doi: 10.3102/0013189X034006003 [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Budgen D, Brereton P (2006) Performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Proc 28th Int Conf Software Engineering, ACM New York, NY, USA, pp. 1051–1052. doi: 10.1145/1134285.1134500 .

- 8. Maier HR (2013) What constitutes a good literature review and why does its quality matter? Environ Model Softw 43: 3–4 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.02.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Sutherland WJ, Fleishman E, Mascia MB, Pretty J, Rudd MA (2011) Methods for collaboratively identifying research priorities and emerging issues in science and policy. Methods Ecol Evol 2: 238–247 doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00083.x [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Kanter SL (2011) Reproducibility of literature search reporting in medical education reviews. Acad Med 86: 1049–1054 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822221e7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Human Res Develop Rev 4: 356–367 doi: 10.1177/1534484305278283 [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Khoo CSG, Na JC, Jaidka K (2011) Analysis of the macro-level discourse structure of literature reviews. Online Info Rev 35: 255–271 doi: 10.1108/14684521111128032 [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Rosenfeld RM (1996) How to systematically review the medical literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115: 53–63 doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70137-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Cook DA, West CP (2012) Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med Educ 46: 943–952 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04328.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dijkers M (2009) The Task Force on Systematic Reviews and Guidelines (2009) The value of “traditional” reviews in the era of systematic reviewing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 88: 423–430 doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31819c59c6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Eco U (1977) Come si fa una tesi di laurea. Milan: Bompiani.

- 17. Hart C (1998) Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE.

- 18. Wagner CS, Roessner JD, Bobb K, Klein JT, Boyack KW, et al. (2011) Approaches to understanding and measuring interdisciplinary scientific research (IDR): a review of the literature. J Informetr 5: 14–26 doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2010.06.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Carnwell R, Daly W (2001) Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract 1: 57–63 doi: 10.1054/nepr.2001.0008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Roberts PD, Stewart GB, Pullin AS (2006) Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol Conserv 132: 409–423 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.04.034 [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ridley D (2008) The literature review: a step-by-step guide for students. London: SAGE.

- 22. Kelleher C, Wagener T (2011) Ten guidelines for effective data visualization in scientific publications. Environ Model Softw 26: 822–827 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.12.006 [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1988) Guidelines for reading literature reviews. CMAJ 138: 697–703. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. May RM (2011) Science as organized scepticism. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 369: 4685–4689 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0177 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Logan DW, Sandal M, Gardner PP, Manske M, Bateman A (2010) Ten simple rules for editing Wikipedia. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000941 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000941 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. van Raan AFJ (2004) Sleeping beauties in science. Scientometrics 59: 467–472 doi: 10.1023/B:SCIE.0000018543.82441.f1 [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Rosenberg D (2003) Early modern information overload. J Hist Ideas 64: 1–9 doi: 10.1353/jhi.2003.0017 [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I (2010) Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med 7: e1000326 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Bertamini M, Munafò MR (2012) Bite-size science and its undesired side effects. Perspect Psychol Sci 7: 67–71 doi: 10.1177/1745691611429353 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Pautasso M (2012) Publication growth in biological sub-fields: patterns, predictability and sustainability. Sustainability 4: 3234–3247 doi: 10.3390/su4123234 [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Michels C, Schmoch U (2013) Impact of bibliometric studies on the publication behaviour of authors. Scientometrics doi: 10.1007/s11192-013-1015-7. In press. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Tsafnat G, Dunn A, Glasziou P, Coiera E (2013) The automation of systematic reviews. BMJ 346: f139 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f139 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Pautasso M, Döring TF, Garbelotto M, Pellis L, Jeger MJ (2012) Impacts of climate change on plant diseases - opinions and trends. Eur J Plant Pathol 133: 295–313 doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-9936-1 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (179.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Peer Review – Best Practices

“Peer review is broken. But let’s do it as effectively and as conscientiously as possible.” — Rosy Hosking, CommLab

“ A thoughtful, well-presented evaluation of a manuscript, with tangible suggestions for improvement and a recommendation that is supported by the comments, is the most valuable contribution that you can make as a reviewer, and such a review is greatly appreciated by both the authors of the manuscript and the editors of the journal. ” — ACS Reviewer Lab

Criteria for success

A successful peer review:

- Contains a brief summary of the entire manuscript. Show the editors and authors what you think the main claims of the paper are, and your assessment of its impact on the field. What did the authors try to show and what did they try to claim?

- Clearly directs the editor on the path forward. Should this paper be accepted, rejected, or revised?

- Identifies any major (internal inconsistencies, missing data, etc.) concerns, and clearly locates them within the document. Why do you think that the direction specified is correct? What were the issues you identified that led you to that decision?

- Lists (if appropriate — i.e. if you are suggesting revision or acceptance) minor concerns to help the authors make the paper watertight (typographical errors, grammatical errors, missing references, unclear explanations of methodology, etc.).

- Explain how the arguments can be better defended through analysis, experiments, etc.

- Is reasonable within the original manuscript scope ; does not suggest modifications that would require excessive time or expense, or that could instead be addressed by adjusting the manuscript’s claims .

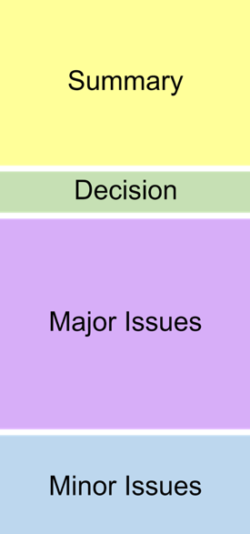

Structure Diagram

A typical peer review is 1-2 pages long. You can divide your content roughly as follows:

Identify your purpose

The purpose of your pre-publication peer review is two-fold:

- Scientific integrity (which can be handled with editorial office assistance)

- Quality of data collection methods and data analysis

- Veracity of conclusions presented in the manuscript

- Determine match between the proposed submission and the journal scope (subject matter and potential impact). For example, a paper that holds significance only for a particular subfield of chemical engineering is not appropriate for a broad multidisciplinary journal. Determining match is usually done in partnership with the editor, who can answer questions of journal scope.

Analyze your audience

The audience for your peer review work is unusual compared to most other kinds of communication you will undertake as a scientist. Your primary audience is the journal editor, who will use your feedback to make a decision to accept or reject the manuscript. Your secondary audience is the author, who will use your suggestions to make improvements to the manuscript. Typically, you will be known to the journal editors, but anonymous to the authors of the manuscript. For this reason, it is important that you balance your review between these two parties.

The editors are most interested in hearing your critical feedback on the science that is presented, and whether there are any claims that need to be adjusted. The editors need to know:

- Your areas of expertise within the manuscript

- The paper’s significance to your particular field

To help you, most journals willhave guidelines for reviewers to follow, which can be found on the journal’s website (e.g., Cell Guidelines ).

The authors are interested in:

- Understanding what aspects of their logic are not easily understood

- Other layers of experimentation or discussion that would be necessary to support claims

- Any additional information they would need to convince you in their arguments

Format Your Document in a Standard Way

Peer review feedback is most easily digested and understood by both editors and authors when it arrives in a clear, logical format. Most commonly the format is (1) Summary, (2) Decision, (3) Major Concerns, and (4) Minor Concerns (see also Structure Diagram above).

There is also often a multiple choice form to “rate” the paper on a number of criteria. This numerical scoring guide may be used by editors to weigh the manuscript against other submissions; think of it mostly as a checklist of topics to cover in your review.

The summary grounds the remainder of your review. You need to demonstrate that you have read and understood the manuscript, which helps the authors understand what other readers are understanding to be the manuscript’s main claims. This is also an opportunity to demonstrate your own expertise and critical thinking, which makes a positive impression on the editors who often may be important people in your field.

It is helpful to use the following guidelines:

- Start with a one-sentence description of the paper’s main point, followed by several sentences summarizing specific important findings that lead to the paper’s logical conclusion.

- Then, highlight the significance of the important findings that were shown in the paper.

- Conclude with the reviewer’s overall opinion of what the manuscript does and does not do well.

Your decision must be clearly stated to aid the interpretation of the rest of your comments (see Criteria for Success). Do this either as part of the concluding sentence in the summary paragraph, or as a separate sentence after the summary. In general, you try to categorize within the following framework:

- Accept with no revisions

- Accept with minor revisions

- Accept with major revisions

Some journals will have specific rules or different wording, so make sure you understand what your options are.

Most reviews also contain the option to provide confidential comments to the editor, which can be used to provide the editor with more detail on the decision. In extreme cases, this can also be where concerns about plagiarism, data manipulation, or other ethical issues can be raised.

The Decision area is also where you can state which aspects of complex manuscripts you feel you have the expertise to comment on.

Major Concerns (where relevant)

Depending on the journal that you are reviewing for, there might be criteria for significance, novelty, industrial relevance, or other field-specific criteria that need to be accounted for in your major concerns. Major concerns, if they are serious, typically lead to decisions that are either “reject” or “accept with major revisions.”

Major concerns include…

- issues with the arguments presented in the paper that are not internally consistent,

- or present arguments that go against significant understanding in the field, without the necessary data to back it up .

- a lack of key experimental or computational data that are vital to justify the claims made in the paper.

- Examples: a study that reports the identity of an unexpected peak in a GC-MS spectrum without accounting for common interferences, or claims pertaining to human health when all the data presented is in a model organism or in vitro .

One of the most important aspects of providing a review with major concerns is your ability to cite resolutions. For example…

- If you think that someone’s argument is going against the laws of thermodynamics, what data would they need to show you to convince you otherwise?

- What types of new statistical analysis would you need to see to believe the claims being made about the clinical trials presented in this work?

- Are there additional control experiments that are needed to show that this catalyst is actually promoting the reaction along the pathway suggested?

Minor Concerns (optional)

Minor concerns are primarily issues that are raised that would improve the clarity of the message, but don’t impact the logic of the argument. Most commonly these are…

- Grammatical errors within the manuscript

- Typographical errors

- Missing references

- Insufficient background or methods information (e.g., an introduction section with only five references)

- Insufficient or possibly extraneous detail

- Unclear or poorly worded explanations (e.g., a paragraph in the discussion section that seems to contradict other parts of the paper)

- Possible options for improving the readability of any graphics (e.g., incorrect labels on a figure)

While minor concerns are not always present in the case of reviews with many major concerns, they are almost always included in the case of manuscripts where the decision is an accept or accept with minor revisions.

Offer revisions that are reasonable and in scope

Think about the feasibility of the experiments you suggest to address your concerns. Are you suggesting 3 years’ more work that could form the basis for a whole other publication? If you are suggesting vast amounts of animal work or sequencing, then are the experiments going to be prohibitively expensive? If the paper would stand without this next layer of experimentation, then think seriously about the real value of these additional experiments. One of the major issues with scientific publishing is the length of time taken to get to the finish line. Don’t muddy the water for fellow authors unnecessarily!

As an alternative to more experiments, does the author need to adjust their claims to fit the extent of their evidence rather than the other way round? If they did that, would this still be a good paper for the journal you are reviewing for?

Structure your comments in a way that makes sense to the audience

Formatting choices:

- Separate each of your concerns clearly with line breaks (or numbering) and organize them in the order they appear in the manuscript.

- Quote directly from the text and bold or italicize relevant phrases to illustrate your points

- Include page and line/paragraph numbers for easy reference.

Style/Concision:

- Keep your comments as brief as possible by simply stating the issue and your suggestion for fixing it in a few sentences or less.

Offer feedback that is constructive and professional

Be unbiased and professional.

Although the identities of the authors are sometimes kept anonymous during the review process (this is rare in chemical and biological research), research communities are typically small and you may try to “guess” who the author is based on the methodology used or the writing style. Regardless, it is important to remain unbiased and professional in your review. Do not assume anything about the paper based on your perception of, for example, the author’s status or the impact their results may have on your own research. If you feel that this might be an issue for you, you must inform the editor that there is a conflict of interest and you should not review this manuscript.

Be polite and diplomatic .

Receiving critical feedback, even when constructive, can be difficult and possibly emotional for the authors. Since you are not anonymous to the editors, being unnecessarily harsh in your feedback will reflect badly on you in the end. Use similar language to what you would use when discussing research at a conference, or when talking with your advisor in a meeting. Manuscript peer review is a good way to practice these “soft” skills which are important yet often neglected in the science community.

Additional resources about effective peer reviewing

- American Chemical Society Reviewer Lab

- Nature.com offers a peer review training course for purchase:

- https://masterclasses.nature.com/courses/205

- http://senseaboutscience.org/activities/peer-review-the-nuts-and-bolts/

- http://asapbio.org/six-essential-reads-on-peer-review

This article was written by Mike Orella (MIT Chem E Comm Lab); edited by Mica Smith (MIT Chem E Comm Lab) and Rosy Hosking (Broad Comm Lab)

- Search Search

- CN (Chinese)

- DE (German)

- ES (Spanish)

- FR (Français)

- JP (Japanese)

- Open science

- Peer Reviewers

- Booksellers

- Corporate Site ↗

- Media Centre ↗

- Publish an article

- Roles and responsibilities

- Signing your contract

- Writing your manuscript

- Submitting your manuscript

- Producing your book

- Promoting your book

- Submit your book idea

- Manuscript guidelines

- Book author services

- Book author benefits

- Publish a book

- Publish conference proceedings

How to peer review

Author tutorials

For science to progress, research methods and findings need to be closely examined and verified, and from them a decision on the best direction for future research is made. After a study has gone through peer review and is accepted for publication, scientists and the public can be confident that the study has met certain standards, and that the results can be trusted.

What you will get from this course

When you have completed this course and the included quizzes, you will have gained the skills needed to evaluate another researcher’s manuscript in a way that will help a journal Editor make a decision about publication. Additionally, having successfully completed the quizzes will let you demonstrate that competence to the wider research community

Topics covered

How the peer review process works.

Journals use peer review to both validate the research reported in submitted manuscripts, and sometimes to help inform their decisions about whether or not to publish that article in their journal.

If the Editor does not immediately reject the manuscript (a “desk rejection”), then the editor will send the manuscript to two or more experts in the field to review it. The experts—called peer reviewers—will then prepare a report that assesses the manuscript, and return it to the editor. After reading the peer reviewer's report, the editor will decide to do one of three things: reject the manuscript, accept the manuscript, or ask the authors to revise and resubmit the manuscript after responding to the peer reviewers’ feedback. If the authors resubmit the manuscript, editors will sometimes ask the same peer reviewers to look over the manuscript again to see if their concerns have been addressed. This is called re-review.

Some of the problems that peer reviewers may find in a manuscript include errors in the study’s methods or analysis that raise questions about the findings, or sections that need clearer explanations so that the manuscript is easily understood. From a journal editor’s point of view, comments on the importance and novelty of a manuscript, and if it will interest the journal’s audience, are particularly useful in helping them to decide which manuscripts to publish.

Will the authors know I am a reviewer? Will I know who the authors are?

Traditionally, peer review worked in a way we now call “closed,” where the editor and the reviewers knew who the authors were, but the authors did not know who the reviewers were. In recent years, however, many journals have begun to develop other approaches to peer review. These include:

- Closed peer review — where the reviewers are aware of the authors’ identities but the authors’ are never informed of the reviewers’ identities.

- Double-blind peer review —where neither author nor reviewer is aware of each other’s identities.

- Open peer review —where authors and reviewers are aware of each other’s identity. In some journals with open peer review the reviewers’ reports are published alongside the article.

The type of peer review used by a journal should be clearly stated in the invitation to review letter you receive and policy pages on the journal website. If, after checking the journal website, you are unsure of the type of peer review used or would like clarification on the journal’s policy you should contact the journal’s editors.

Why serve as a peer reviewer?

As your career advances, you are likely to be asked to serve as a peer reviewer.

As well as supporting the advancement of science, and providing guidance on how the author can improve their paper, there are also some benefits of peer reviewing to you as a researcher:

- Serving as a peer reviewer looks good on your CV as it shows that your expertise is recognized by other scientists. (See the supplemental material about the Web of Science Reviewer Recognition Service to learn more about getting credit for the reviews you do. Also see the supplemental material about ORCiD iDs to learn how to connect your reviews to your unique ORCiD iD.)

- You will get to read some of the latest science in your field well before it is in the public domain.

- The critical thinking skills needed during peer review will help you in your own research and writing.

Who does peer review benefit?

When performed correctly peer review helps improve the clarity, robustness and reproducibility of research.

When peer reviewing, it is helpful to think from the point of view of three different groups of people:

- Authors . Try to review the manuscript as you would like others to review your work. When you point out problems in a manuscript, do so in a way that will help the authors to improve the manuscript. Even if you recommend to the editor that the manuscript be rejected, your suggested revisions could help the authors prepare the manuscript for submission to a different journal.

- Journal editors . Comment on the importance and novelty of the study. Editors will use your comments to assess whether the manuscript is of the right level of impact for the journal. Your comments and opinions on the paper are much more important that a simple recommendation; editors need to know why you think a paper should be published or rejected as your reasoning will help inform their decision.

- Readers . Identify areas that need clarification to make sure other readers can easily understand the manuscript. As a reviewer, you can also save readers’ time and frustration by helping to keep unimportant or error filled research out of the published literature.

Writing a thorough, thoughtful review usually takes several hours or more. But by taking the time to be a good reviewer, you will be providing a service to the scientific community.

Accepting an invitation to review

Editors invite you to review as they believe that you are an expert in a certain area. They would have judged this from your previous publication record or posters and/or sessions you have contributed to at conferences. You may find that the number of invitations to review increases as you progress in your career.

There are several questions to consider before you accept an invitation to review a paper.

- Are you qualified? The editor has asked you to review the manuscript because he or she believes you are familiar with the specific topic or research method used in the paper. It will usually be okay if you can review some, but not all, aspects of a manuscript. Take as an example, if the study focused on a certain physiological process in an animal model you conduct your research on but used a technique that you have never used. In this case, simply review the parts of the manuscript that are in your area of expertise, and tell the editor which parts you cannot review. However, if the manuscript is too far outside your area, you should decline to review it.

- Do you have time? If you know you will not be able to review the manuscript by the deadline, then you should not accept the invitation. Sending in a review long after the deadline will delay the publication process and frustrate the editor and authors. Keep in mind that reviewing manuscripts, like research and teaching, is a valuable contribution to science, and is worth making time for whenever possible.

- The reported results could cause you to make or lose money, e.g., the authors are developing a drug that could compete with a drug you are working on.

- The manuscript concerns a controversial question that you have strong feelings about (either agreeing or disagreeing with the authors).

- You have strong positive or negative feelings about one of the authors, e.g., a former teacher who you admire greatly.

- You have published papers or collaborated with one of the co-authors in recent years.

If you are not sure if you have a conflict of interest, discuss your circumstances with the editor.

Along with avoiding a conflict of interest, there are several other ethical guidelines to keep in mind as you review the manuscript. Manuscripts under review are highly confidential, so you should not discuss the manuscript – or even mention its existence – to others. One exception is if you would like to consult with a colleague about your review; in this case, you will need to ask the editor’s permission. It is normally okay to ask one of your students or postdocs to help with the review. However, you should let the editor know that you are being helped, and tell your assistant about the need for confidentiality. In some cases case, when the journal operates an open peer review policy they will allow the student or postdoc to co-sign the report with you should they wish.

It is very unethical to use information in the manuscript to make business decisions, such as buying or selling stock. Also, you should never plagiarize the content or ideas in the manuscript.

Next: Evaluating manuscripts

For further support

We hope that with this tutorial you have a clearer idea of how the peer review process works and feel confident in becoming a peer reviewer.

If you feel that you would like some further support with writing, reviewing, and publishing, Springer Nature offer some services which may be of help.

- Nature Research Editing Service offers high quality English language and scientific editing. During language editing , Editors will improve the English in your manuscript to ensure the meaning is clear and identify problems that require your review. With Scientific Editing experienced development editors will improve the scientific presentation of your research in your manuscript and cover letter, if supplied. They will also provide you with a report containing feedback on the most important issues identified during the edit, as well as journal recommendations.

- Our affiliates American Journal Experts also provide English language editing* as well as other author services that may support you in preparing your manuscript.

- We provide both online and face-to-face training for researchers on all aspects of the manuscript writing process.

* Please note, using an editing service is neither a requirement nor a guarantee of acceptance for publication.

Test your knowledge

Take the Quiz!

Stay up to date

Here to foster information exchange with the library community

Connect with us on LinkedIn and stay up to date with news and development.

- Tools & Services

- Account Development

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Media Centre

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2024 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted? This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report. Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow.

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing, is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

By reviewing a paper and liaising with the editorial office, you will gain first-hand experience of the key considerations that go into the publication decision, as well as commonly recommended revisions. Keeping up to date with novel research in your field.

Read the work in its entirety to get an overall sense of the content, structure, and style of a work before conducting a focused reading or review. Know what to look for.

Peer review is a critically important service for maintaining quality in the scientific literature. Peer review of a scientific manuscript and the associated reviewer's report should assess specific details related to the accuracy, validity, novelty, and interpretation of a study's results.

In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors. How to choose which topic to review?

In this paper, drawing on the relevant medical literature and our collective experience as peer reviewers, we provide a user guide to the peer review process, including discussion of the purpose and limitations of peer review, the qualities of a good peer reviewer, and a step-by-step process of how to conduct an effective peer review.

Peer review feedback is most easily digested and understood by both editors and authors when it arrives in a clear, logical format. Most commonly the format is (1) Summary, (2) Decision, (3) Major Concerns, and (4) Minor Concerns (see also Structure Diagram above).

Journals use peer review to both validate the research reported in submitted manuscripts, and sometimes to help inform their decisions about whether or not to publish that article in their journal.