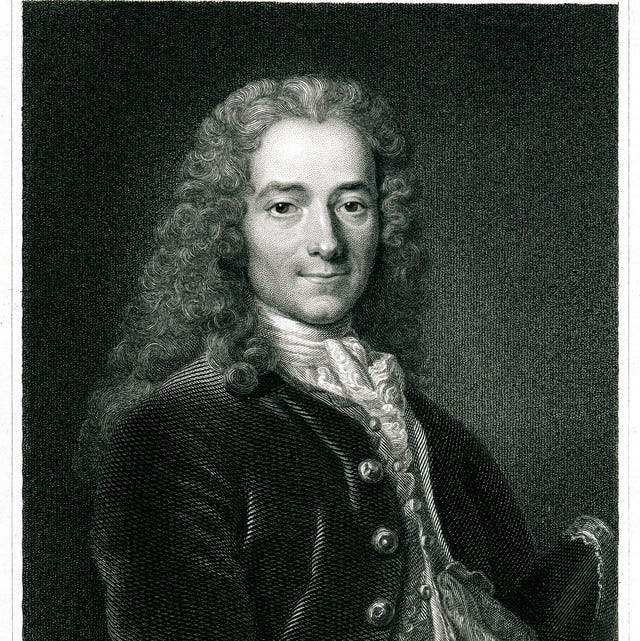

Author of the satirical novella 'Candide,' Voltaire is widely considered one of France's greatest Enlightenment writers.

Who Was Voltaire?

Voltaire established himself as one of the leading writers of the Enlightenment. His famed works include the tragic play Zaïre , the historical study The Age of Louis XIV and the satirical novella Candide . Often at odds with French authorities over his politically and religiously charged works, he was twice imprisoned and spent many years in exile. He died shortly after returning to Paris in 1778.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: François-Marie Arouet BORN: November 21, 1694 DIED: May 30, 1778 BIRTHPLACE: Paris, France ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Scorpio

Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet to a prosperous family on November 21, 1694, in Paris. He was the youngest of five children born to François Arouet and Marie Marguerite d'Aumart. When Voltaire was just seven years old, his mother passed away. Following her death, he grew closer to his free-thinking godfather.

In 1704, Voltaire was enrolled at the Collége Louis-le-Grand, a Jesuit secondary school in Paris, where he received a classical education and began showing promise as a writer.

Beliefs and Philosophy

Embracing Enlightenment philosophers such as Isaac Newton , John Locke and Francis Bacon , Voltaire found inspiration in their ideals of a free and liberal society, along with freedom of religion and free commerce.

Voltaire, in keeping with other Enlightenment thinkers of the era, was a deist — not by faith, according to him, but rather by reason. He looked favorably on religious tolerance, even though he could be severely critical towards Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

As a vegetarian and an advocate of animal rights, however, Voltaire praised Hinduism, stating Hindus were "[a] peaceful and innocent people, equally incapable of hurting others or of defending themselves."

Major Works

Voltaire wrote poetry and plays, as well as historical and philosophical works. His most well-known poetry includes The Henriade (1723) and The Maid of Orleans , which he started writing in 1730 but never fully completed.

Among the earliest of Voltaire's best-known plays is his adaptation of Sophocles' tragedy Oedipus , which was first performed in 1718. Voltaire followed with a string of dramatic tragedies, including Mariamne (1724). His Zaïre (1732), written in verse, was something of a departure from previous works: Until that point, Voltaire's tragedies had centered on a fatal flaw in the protagonist's character; however, the tragedy in Zaïre was the result of circumstance. Following Zaïre, Voltaire continued to write tragic plays, including Mahomet (1736) and Nanine (1749).

Voltaire's body of writing also includes the notable historical works The Age of Louis XIV (1751) and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). In the latter, Voltaire took a unique approach to tracing the progression of world civilization by focusing on social history and the arts.

Voltaire's popular philosophic works took the form of the short stories Micromégas (1752) and Plato's Dream (1756), as well as the famed satirical novella Candide (1759), which is considered Voltaire's greatest work. Candide is filled with philosophical and religious parody, and in the end the characters reject optimism. There is great debate on whether Voltaire was making an actual statement about embracing a pessimistic philosophy or if he was trying to encourage people to be actively involved to improve society.

In 1764, he published another of his acclaimed philosophical works, Dictionnaire philosophique , an encyclopedic dictionary that embraced the concepts of Enlightenment and rejected the ideas of the Roman Catholic Church.

Arrests and Exiles

In 1716, Voltaire was exiled to Tulle for mocking the duc d'Orleans. In 1717, he returned to Paris, only to be arrested and exiled to the Bastille for a year on charges of writing libelous poetry. Voltaire was sent to the Bastille again in 1726, for arguing with the Chevalier de Rohan. This time he was only detained briefly before being exiled to England, where he remained for nearly three years.

The publication of Voltaire's Letters on the English (1733) angered the French church and government, forcing the writer to flee to safer pastures. He spent the next 15 years with his mistress, Émilie du Châtelet, at her husband's home in Cirey-sur-Blaise.

Voltaire moved to Prussia in 1750 as a member of Frederick the Great's court, and spent later years in Geneva and Ferney. By 1778, he was recognized as an icon of the Enlightenment's progressive ideals, and he was given a hero's welcome upon his return to Paris. He died there shortly afterward, on May 30, 1778.

In 1952, researcher and writer Theodore Besterman established a museum devoted to Voltaire in Geneva. He later set about writing a biography of his favorite subject, and following his death in 1976, the Voltaire Foundation was vested permanently at the University of Oxford.

The foundation continued to work toward making the Enlightenment writer's prolific output available to the public. It was later announced that The Oxford Complete Works of Voltaire , the first exhaustive annotated edition of Voltaire’s novels, plays and letters, would expand to 220 volumes by 2020.

In November 2017, during an event to celebrate what would have been Voltaire's 323rd birthday, foundation director Nicholas Cronk explained how the famed writer used inaccuracies to generate attention. Among his fabrications, Voltaire offered up differing dates for his birthday and lied about the identity of his biological father.

- A witty saying proves nothing.

- All murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Philosophers

Noam Chomsky

Marcus Garvey

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

- World Biography

Voltaire Biography

Born: November 21, 1694 Paris, France Died: May 30, 1778 Paris, France French poet and philosopher

The French poet, dramatist, historian, and philosopher Voltaire was an outspoken and aggressive enemy of every injustice but especially of religious intolerance (the refusal to accept or respect any differences).

Early years

Voltaire was born as François Marie Arouet, perhaps on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. He was the youngest of the three surviving children of François Arouet and Marie Marguerite Daumand, although Voltaire claimed to be the "bastard [born out of wedlock] of Rochebrune," a minor poet and songwriter. Voltaire's mother died when he was seven years old, and he developed a close relationship with his godfather, a free-thinker. His family belonged to the upper-middle-class, and young Voltaire was able to receive an excellent education. A clever child, Voltaire studied under the Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand from 1704 to 1711. He displayed an astonishing talent for poetry and developed a love of the theater and literature.

Emerging poet

When Voltaire was drawn into the circle of the seventy-two-year-old poet Abbé de Chaulieu, his father packed him off to Caen, France. Hoping to stop his son's literary ambitions and to turn his mind to pursuing law, Arouet placed the youth as secretary to the French ambassador at The Hague, the seat of government in the Netherlands. Voltaire fell in love with a French refugee, Catherine Olympe Dunoyer, who was pretty but barely educated. Their marriage was stopped. Under the threat of a lettre de cachet (an official letter from a government calling for the arrest of a person) obtained by his father, Voltaire returned to Paris in 1713 and was contracted to a lawyer. He continued to write and he renewed his pleasure-loving acquaintances. In 1717 Voltaire was at first exiled (forced to leave) and then imprisoned in the Bastille, an enormous French prison, for writings that were offensive to powerful people.

While Voltaire stayed in England (1726–1728) he was greatly honored; Alexander Pope (1688–1744), William Congreve (1670–1729), Horace Walpole (1717–1797), and Henry St. John, Viscount Bolingbroke (1658–1751), praised him; and his works earned Voltaire one thousand pounds. Voltaire learned English by attending the theater daily, script in hand. He also absorbed English thought, especially that of John Locke (1632–1704) and Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), and he saw the relationship between free government and creative business developments. More importantly, England suggested the relationship of wealth to freedom. The only protection, even for a brilliant poet, was wealth.

At Cirey and at court, 1729–1753

Voltaire returned to France in 1729. One product of his English stay was the Lettres anglaises (1734), which have been called "the first bomb dropped on the Old Regime." Their explosive potential (something that shows future promise) included such remarks as, "It has taken centuries to do justice to humanity, to feel it was horrible that the many should sow and the few should reap." Written in the style of letters to a friend in France, the twenty-four "letters" were a clever and seductive (desirable) call for political, religious, and philosophic (having to do with knowledge) freedom; for the betterment of earthly life; for employing the method of Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Locke, and Newton; and generally for striving toward social progress.

Prior to 1753 Voltaire did not have a home; but for fifteen years following 1733 he had stayed in Cirey, France, in a château (country house) owned by Madame du Châtelet. While still living with her patient husband and son, Émilie made generous room for Voltaire. They were lovers; and they worked together intensely on physics and metaphysics, a philosophy which investigates the nature of reality.

Honored by a respectful correspondence with Frederick II of Prussia (1712–1786), Voltaire was then sent on diplomatic (having to do with international affairs) missions to Prussia. But Voltaire's new interest was his affair with his widowed niece, Madame Denis. This affair continued its passionate and stormy course to the last years of his life. Émilie, too, found solace in other lovers. The simple and peaceful time of Cirey ended with her death in 1749.

Voltaire then accepted Frederick's repeated invitation to live at court. He arrived at Potsdam (now in Germany) with Madame Denis in July 1750. First flattered by Frederick's hospitality, Voltaire then gradually became anxious, quarrelsome, and finally bored. He left, angry, in March 1753, having written in December 1752: "I am going to write for my instruction a little dictionary used by Kings. 'My friend' means 'my slave.'" Frederick took revenge by delaying permission for Voltaire's return to France, by putting him under a week's house arrest at the German border, and by seizing all his money.

Sage of Ferney, 1753–1778

Voltaire's literary productivity did not slow down, although his concerns shifted as the years passed while at his estate in Ferney, France. He was best known as a poet until in 1751 Le Siècle de Louis XIV marked him also as a historian. Other historical works include Histoire de Charles XII; Histoire de la Russie sous Pierre le Grand; and the universal history, Essai sur l'histoire générale et sur les moeurs et l'esprit des nations, published in 1756 but begun at Cirey. An extremely popular dramatist until 1760, he began to be outdone by competition from the plays of William Shakespeare (1564–1616) that he had introduced to France.

The philosophic conte (a short story about adventure) was a Voltaire invention. In addition to his famous Candide (1759), others of his stories in this style include Micromégas, Vision de Babouc, Memnon, Zadig, and Jeannot et Colin. In addition to the Lettres Philosophiques and the work on Newton (1642–1727), others of Voltaire's works considered philosophic are Philosophie de l'histoire, Le Philosophe ignorant, Tout en Dieu, Dictionnaire philosophique portatif, and Traité de la métaphysique. Voltaire's poetry includes—in addition to the Henriade —the philosophic poems L'Homme, La Loi naturelle, and Le Désastre de Lisbonne, as well as the famous La Pucelle, a delightfully naughty poem about Joan of Arc (1412–1431).

Always the champion of liberty, Voltaire in his later years became actively involved in securing justice for victims of persecution, or intense harassment. He became the "conscience of Europe." His activity in the Calas affair was typical. An unsuccessful and depressed young man had hanged himself in his Protestant father's home in Roman Catholic city of Toulouse, France. For two hundred years Toulouse had celebrated the massacre (cruel killings) of four thousand of its Huguenot inhabitants (French Protestants). When the rumor spread that the dead man had been about to abandon Protestantism, the family was seized and tried for murder. The father was tortured; a son was exiled (forced to leave); and the daughters were forcefully held in a convent (a house for nuns). Investigation assured Voltaire of their innocence, and from 1762 to 1765 he worked in their behalf. He employed "his friends, his purse, his pen, his credit" to move public opinion to the support of the Calas family. In 1765, Parliament declared the Calas family innocent.

Voltaire's influence continued to be felt after his death in Paris on May 30, 1778.

For More Information

Carlson, Marvin. Voltaire and the Theatre of the Eighteenth Century. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Mason, Haydn. Voltaire: A Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981.

McLean, Jack. Hopeless But Not Serious: The Autobiography of the Urban Voltaire. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mainstream Pub. Projects, 1996.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- European History ›

- European History Figures & Events ›

The Life and Work of Voltaire, French Enlightenment Writer

Kean Collection / Getty Images

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

Born François-Marie Arouet, Voltaire (November 21, 1694 – May 30, 1778) was a writer and philosopher of the French Enlightenment period . He was an incredibly prolific writer, advocating for civil freedoms and criticizing major institutions such as the Catholic Church.

Fast Facts: Voltaire

- Full Name : François-Marie Arouet

- Occupation : Writer, poet, and philosopher

- Born : November 21, 1694 in Paris, France

- Died : May 30, 1778 in Paris, France

- Parents: François Arouet and Marie Marguerite Daumard

- Key Accomplishments : Voltaire published significant criticism of the French monarchy. His commentary on religious tolerance, historiographies, and civil liberties became a key component of Enlightenment thinking.

Voltaire was the fifth child and fourth son of François Arouet and his wife Marie Marguerite Daumard. The Arouet family had already lost two sons, Armand-François and Robert, in infancy, and Voltaire (then François-Marie) was nine years younger than his surviving brother, Armand, and seven years younger than his sole sister, Marguerite-Catherine. François Arouet was a lawyer and a treasury official; their family was part of the French nobility , but at the lowest possible rank. Later in life, Voltaire claimed to be the illegitimate son of a higher-ranked nobleman by the name of Guérin de Rochebrune.

His early education came from the Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand. From the age of ten until seventeen, Voltaire received classical instruction in Latin, rhetoric , and theology. Once he left school, he decided he wanted to become a writer, much to the dismay of his father, who wanted Voltaire to follow him into the law. Voltaire also continued learning outside the confines of formal education. He developed his writing talents and also became multilingual, attaining fluency in English, Italian, and Spanish in addition to his native French.

First Career and Early Romance

After leaving school, Voltaire moved to Paris. He pretended to be working as an assistant to a notary, theoretically as a stepping stone into the legal profession. In reality, though, he was actually spending most of his time writing poetry. After a time, his father found out the truth and sent him away from Paris to study law in Caen, Normandy.

Even this did not deter Voltaire from continuing to write. He merely switched over from poetry to writing studies on history and essays. During this period, the witty style of writing and speaking that made Voltaire so popular first appeared in his work, and it endeared him to many of the higher-ranking nobles he spent time around.

In 1713, with his father’s assistance, Voltaire began working at the Hague in the Netherlands as a secretary to the French ambassador, the marquis de Châteauneuf. While there, Voltaire had his earliest known romantic entanglement, falling in love with a Huguenot refugee, Catherine Olympe Dunoyer. Unfortunately, their connection was considered unsuitable and caused something of a scandal, so the marquis forced Voltaire to break it off and return to France. By this point, his political and legal career had all but been given up.

Playwright and Government Critic

Upon returning to Paris, Voltaire launched his writing career. Since his favorite topics were critiques of the government and satires of political figures, he landed in hot water pretty quickly. One early satire, which accused the Duke of Orleans of incest, even landed him in prison in the Bastille for nearly a year. Upon his release, however, his debut play (a take on the Oedipus myth ) was produced, and it was a critical and commercial success. The Duke whom he had previously offended even presented him with a medal in recognition of the achievement.

It was around this time that François-Marie Arouet began going by the pseudonym Voltaire, under which he would publish most of his works. To this day, there’s much debate as to how he came up with the name. It may have its roots as an anagram or pun on his family name or several different nicknames. Voltaire reportedly adopted the name in 1718, after being released from the Bastille. After his release, he also struck up a new romance with a young widow, Marie-Marguerite de Rupelmonde.

Unfortunately, Voltaire’s next works did not have nearly the same success as his first. His play Artémire flopped so badly that even the text itself only survives in a few fragments, and when he tried to publish an epic poem about King Henry IV (the first Bourbon dynasty monarch), he couldn’t find a publisher in France. Instead, he and Rupelmonde journeyed to the Netherlands, where he secured a publisher in The Hague. Eventually, Voltaire convinced a French publisher to publish the poem, La Henriade , secretly. The poem was a success, as was his next play, which was performed at the wedding of Louis XV.

In 1726, Voltaire became involved in a quarrel with a young nobleman who reportedly insulted Voltaire’s change of name. Voltaire challenged him to a duel, but the nobleman instead had Voltaire beaten, then arrested without a trial. He was, however, able to negotiate with authorities to be exiled to England rather than imprisoned at the Bastille again.

English Exile

As it turns out, Voltaire’s exile to England would change his entire outlook. He moved in the same circles as some of the leading figures of English society, thought, and culture, including Jonathan Swift , Alexander Pope, and more. In particular, he became fascinated by the government of England in comparison with France: England was a constitutional monarchy , whereas France still lived under an absolute monarchy . The country also had greater freedoms of speech and religion, which would become a key component of Voltaire’s criticisms and writings.

Voltaire was able to return to France after a little more than two years, though still banned from the court at Versailles. Thanks to participation in a plan to literally purchase the French lottery, along with an inheritance from his father, he quickly became incredibly rich. In the early 1730s, he began publishing work that showed his clear English influences. His play Zaïre was dedicated to his English friend Everard Fawkener and included praise of English culture and freedoms. He also published a collection of essays that praised British politics, attitudes towards religion and science, and arts and literature, called the Letters Concerning the English Nation , in 1733 in London. The next year, it was published in French, landing Voltaire in hot water again. Because he did not get the approval of the official royal censor before publishing, and because the essays praised British religious freedom and human rights, the book was banned and Voltaire had to quickly flee from Paris.

In 1733, Voltaire also met the most significant romantic partner of his life: Émilie, the Marquise du Châtelet, a mathematician who was married to the Marquis du Châtelet. Despite being 12 years younger than Voltaire (and married, and a mother), Émilie was very much an intellectual peer to Voltaire. They amassed a shared collection of over 20,000 books and spent time studying and performing experiments together, many of which were inspired by Voltaire’s admiration of Sir Isaac Newton . After the Letters scandal, Voltaire fled to the estate belonging to her husband. Voltaire paid to renovate the building, and her husband did not raise any fuss about the affair, which would continue for 16 years.

Somewhat abashed by his multiple conflicts with the government, Voltaire began keeping a lower profile, although he continued his writing, now focused on history and science. The Marquise du Châtelet contributed considerably alongside him, producing a definitive French translation of Newton’s Principia and writing reviews of Voltaire’s Newton-based work. Together, they were instrumental in introducing Newton’s work in France. They also developed some critical views on religion, with Voltaire publishing several texts that sharply criticized the establishment of state religions, religious intolerance, and even organized religion as a whole. Similarly, he railed against the style of histories and biographies of the past, suggesting they were filled with falsehoods and supernatural explanations and needed a fresh, more scientific and evidence-based approach to research.

Connections in Prussia

Frederick the Great , while he was still just the crown prince of Prussia, began a correspondence with Voltaire around 1736, but they did not meet in person until 1740. Despite their friendship, Voltaire still went to Frederick’s court in 1743 as a French spy to report back on Frederick’s intentions and capabilities with regards to the ongoing War of Austrian Succession.

By the mid-1740s, Voltaire’s romance with the Marquise du Châtelet had begun to wind down. He grew tired of spending nearly all his time at her estate, and both found new companionship. In Voltaire’s case, it was even more scandalous than their affair had been: he was attracted to, and later lived with, his own niece, Marie Louise Mignot. In 1749, the Marquise died in childbirth, and Voltaire moved to Prussia the following year.

During the 1750s, Voltaire’s relationships in Prussia began to deteriorate. He was accused of theft and forgery relating to some bond investments, then had a feud with the president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences that ended with Voltaire writing a satire that angered Frederick the Great and resulted in the temporary destruction of their friendship. They would, however, reconcile in the 1760s .

Geneva, Paris, and Final Years

Forbidden by King Louis XV to return to Paris, Voltaire instead arrived in Geneva in 1755. He continued publishing, with major philosophical writings such as Candide, or Optimism , a satire of Leibniz's philosophy of optimistic determinism which would become Voltaire’s most famous work.

Starting in 1762, Voltaire took up the causes of unjustly persecuted people, particularly those who were victims of religious persecution. Among his most notable causes was the case of Jean Calas, a Huguenot who was convicted of murdering his son for wanting to convert to Catholicism and tortured to death; his property was confiscated and his daughters forced into Catholic convents. Voltaire, along with others, strongly doubted his guilt and suspected a case of religious persecution. The conviction was overturned in 1765.

Voltaire’s last year was still full of activity. In early 1778, he was initiated into Freemasonry , and historians dispute as to whether he did so at the urging of Benjamin Franklin or not. He also returned to Paris for the first time in a quarter century to see his latest play, Irene , open. He fell ill on the journey and believed himself to be on death’s doorstep, but recovered. Two months later, however, he became ill again and died on May 30, 1778. Accounts of his deathbed vary wildly, depending on the sources and their own opinions of Voltaire. His famous deathbed quote—in which a priest asked him to renounce Satan and he replied “Now is not the time for making new enemies!”—is likely apocryphal and actually traced to a 19 th -century joke that was attributed to Voltaire in the 20 th century.

Voltaire was formally denied a Christian burial because of his criticism of the Church, but his friends and family managed to secretly arrange a burial at the abbey of Scellières in Champagne. He left behind a complicated legacy. For instance, while he argued for religious tolerance, he also was one of the origins of Enlightenment-era anti-Semitism. He endorsed anti-enslavement and anti-monarchical views, but disdained the idea of democracy as well. In the end, Voltaire’s texts became a key component of Enlightenment thinking , which has allowed his philosophy and writing to endure for centuries.

- Pearson, Roger. Voltaire Almighty: A Life in Pursuit of Freedom . Bloomsbury, 2005.

- Pomeau, René Henry. “Voltaire: French Philosopher and Author.” Encyclopaedia Britannica , https://www.britannica.com/biography/Voltaire.

- “Voltaire.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Stanford University, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/voltaire/

- 18 Key Thinkers of the Enlightenment

- Notable Writers from European History

- Biography of Louis XV, Beloved King of France

- Daniel O'Connell of Ireland, The Liberator

- The Life of Madame de Pompadour, Royal Mistress and Advisor

- Biography of Marie-Antoinette, French Queen Consort

- Sarah Bernhardt: Groundbreaking Actress of the 19th Century

- Biography of Marquis de Sade, French Novelist and Libertine

- Biography of Napoleon Bonaparte, Great Military Commander

- Biography of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia

- Biography of Margaret of Valois, France’s Slandered Queen

- Influential Leaders in European History

- Biography of Queen Anne, Britain's Forgotten Queen Regnant

- Wallis Simpson: Her Life, Legacy, and Marriage to Edward VIII

- Henry V of England

- Biography of Lorenzo de' Medici

Biography Online

Voltaire Biography

“Love truth, but pardon error.”

– Voltaire

Voltaire was a prolific writer, producing more than 20,000 letters and over 2,000 books and pamphlets. Despite strict censorship laws, he frequently risked large penalties by breaking them and questioning the establishment.

Short Biography of Voltaire

Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet, in Paris. He was educated by Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704–1711), becoming fluent in Greek, Latin and the major European languages.

His father tried to encourage Voltaire to become a lawyer, but Voltaire was more interested in becoming a writer. Instead of studying to be a lawyer, he began writing poetry and mild criticisms of the church and state. His humorous, satirical writing made him popular with sections of Paris society, though they also started attracting the attention of the censors.

In 1726, he was exiled to England after being involved in a scuffle with a French nobleman. The nobleman used his wealth to have him arrested, and this would cause Voltaire to try and reform the French judicial system. After this first imprisonment in the Bastilles, he changed his name to Voltaire – signifying his departure from his past. He also used numerous other pen names throughout the course of his life, in a bid to escape censorship.

Voltaire spent three years in England, where he was influenced by British writers, such as William Shakespeare and also the different political system, which saw a constitutional monarchy rather than an absolute monarchy as in France. He also learnt from great scientists, such as Sir Isaac Newton . Voltaire was particularly impressed by the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, such as Adam Smith and David Hume, saying once:

“We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation”

Although he had much in common with fellow French Enlightenment philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau , the pair often disagreed and had a prickly relationship. However, after Rousseau wrote Emile / Vicaire Savoyard, Voltaire offered Rousseau a safe haven because he appreciated Rousseau’s attack on religious hypocrisy. Rousseau regretted not replying to Voltaire’s offer.

On returning to France, he wrote letters praising the British system of government and their greater respect for freedom of speech. This enraged the French establishment, and again he was forced to flee Paris.

Seeking a safe place, Voltaire began a collaboration with Marquise du Chatelet. During this time, Voltaire wrote on Newton’s scientific theories and helped to make Newton’s ideas accessible to a much wider section of European society. He also began attacking the church’s relationship with the state. Voltaire argued for the separation of religion and state and also allowing freedom of belief and religious tolerance. Voltaire had a mixed opinion of the Bible and was willing to criticise it. Though not professing a religion, he believed in God, as a matter of reason.

“What is faith? Is it to believe that which is evident? No. It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason.” On Catholicism

In a letter to Frederick II, King of Prussia, (5 January 1767) he once wrote:

“Ours [religion] is without a doubt the most ridiculous, the most absurd, and the most blood-thirsty ever to infect the world.”

In 1744, Voltaire returned to Paris, where he began a relationship with his niece, Marie Louise Mignot. They remained together until his death.

For a brief time, he was invited by Frederick the Great, to Potsdam. Here, Voltaire wrote more articles of a scientific nature, but later incurred the displeasure of the king as he started satirising the abuses of power within the state.

In 1759, he wrote his best-known work – Candide, ou l’Optimisme ( Candide , or Optimism ) This was a satire on the philosophy of Leibniz. After a brief stay in Geneva, he settled for 20 years in Ferny on the French border.

In his later life, Voltaire continued to write and also to support persecuted religious minorities. He was visited by some of the leading European intellectuals of the day – such as James Boswell and Adam Smith.

In 1778, he died after shortly returning to Paris. Some of his enemies claimed he made a deathbed conversion to Catholicism, but this is disputed.

In February of that year, fearing he would die, he wrote:

“I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition.”

Voltaire was secretly buried before a pronouncement could be made public.

Three years after his death, on 11 July 1791, he was brought back to Paris to be enshrined in the Pantheon. It is said up to a million people came to see Voltaire – now considered a French hero and fore-runner of the French revolution.

Influence of Voltaire

- Voltaire revolutionised the art of history. He sought to avoid bias and included discussion of social and economic issues, moving away from dry military accounts.

- Voltaire argued for an extension of education, hoping greater literacy would free society from ignorance.

- Voltaire wrote poems and plays, including two epics. Voltaire politicised writing by showing that even poetry and romance could be laced with satire and political polemic. Often it was indirect criticism that was most effective.

- Voltaire was a passionate and persistent critic of those in power who misused their position. By attacking the abuses of the absolute monarchy and church, he paved the way for a less deferential attitude which was a significant underlying cause of the French revolution.

- At a time of religious persecution, Voltaire illustrated how religious dogmas were created by human ignorance and led to needless bloodshed and suffering.

- Voltaire was a key figure of the enlightenment which sought to use a range of scientific and literary books to explain the underlying nature of life. Voltaire believed no one book or dogma could explain everything. But, true understanding required the use of reason and an open mind.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “ Biography of Voltaire” , Oxford, www.biographyonline.net – 3 February 2013. Last updated 7 February 2018.

Voltaire Quotes

“It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?”

– Voltaire A Treatise on Toleration (1763)

Candide – Voltaire

Candide – Voltaire at Amazon

The Portable Voltaire

The Portable Voltaire at Amazon

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

10 Things You Should Know About Voltaire

By: Evan Andrews

Updated: August 8, 2023 | Original: November 21, 2014

1. The origins of his famous pen name are unclear.

Voltaire had a strained relationship with his father, who discouraged his literary aspirations and tried to force him into a legal career. Possibly to show his rejection of his father’s values, he dropped his family name and adopted the nom de plume “Voltaire” upon completing his first play in 1718.

Voltaire never explained the meaning of his pen name, so scholars can only speculate on its origins. The most popular theory maintains the name is an anagram of a certain Latinized spelling of “Arouet,” but others have claimed it was a reference to the name of a family chateau or a nod to the nickname “volontaire” (volunteer), which Voltaire may have been given as a sarcastic reference to his stubbornness.

2. He was imprisoned in the Bastille for nearly a year.

Voltaire’s caustic wit first got him into trouble with the authorities in May 1716, when he was briefly exiled from Paris for composing poems mocking the French regent’s family. The young writer was unable to bite his tongue, however, and only a year later he was arrested and confined to the Bastille for writing scandalous verse implying the regent had an incestuous relationship with his daughter.

Voltaire boasted that his cell gave him some quiet time to think, and he eventually did 11 months behind bars before winning a release. He later endured another short stint in the Bastille in April 1726, when he was arrested for planning to duel an aristocrat that had insulted and beaten him. To escape further jail time, he voluntarily exiled himself to England, where he remained for nearly three years.

3. He became hugely wealthy by exploiting a flaw in the French lottery.

In 1729, Voltaire teamed with mathematician Charles Marie de La Condamine and others to exploit a lucrative loophole in the French national lottery. The government shelled out massive prizes for the contest each month, but an error in calculation meant that the payouts were larger than the value of all the tickets in circulation. With this in mind, Voltaire, La Condamine and a syndicate of other gamblers were able to repeatedly corner the market and rake in massive winnings.

The scheme left Voltaire with a windfall of nearly half a million francs, setting him up for life and allowing him to devote himself solely to his literary career.

4. He was an extraordinary prolific writer.

Voltaire wrote more than 50 plays, dozens of treatises on science, politics and philosophy, and several books of history on everything from the Russian Empire to the French Parliament. Along the way, he also managed to squeeze in heaps of verse and a voluminous correspondence amounting to some 20,000 letters to friends and contemporaries.

Voltaire supposedly kept up his prodigious output by spending up to 18 hours a day writing or dictating to secretaries, often while still in bed. He may have also been fueled by heroic amounts of caffeine—according to some sources, he drank as many as 40 cups a day.

5. Many of his most famous works were banned.

Since his writing denigrated everything from organized religion to the justice system, Voltaire ran up against frequent censorship from the French government. A good portion of his work was suppressed, and the authorities even ordered certain books to be burned by the state executioner.

To combat the censors, Voltaire had much of his output printed abroad, and he published under a veil of assumed names and pseudonyms. His famous novella “Candide” was originally attributed to a “Dr. Ralph,” and he actively tried to distance himself from it for several years after both the government and the church condemned it.

Despite his best attempts to remain anonymous, Voltaire lived in almost constant fear of arrest. He was forced to flee to the French countryside after his “Letters Concerning the English Nation” was released in 1734, and he went on to spend the majority of his later life in unofficial exile in Switzerland.

6. He helped popularize the famous tale about Sir Isaac Newton and the apple.

Though the two never met in person, Voltaire was an enthusiastic acolyte of the English physicist and mathematician Sir Isaac Newton. Upon receiving a copy of Newton’s “Principia Mathematica,” he claimed he knelt down before it in reverence, “as was only right.”

Voltaire played a key role in popularizing Newton’s ideas, and he offered one of the first accounts of how the famed scientist developed his theories on gravity. In his 1727 “Essay on Epic Poetry,” Voltaire wrote that Newton “had the first thought of his System of Gravitation, upon seeing an apple falling from a tree.”

Voltaire wasn’t the original source for the story of the “Eureka!” moment, as has often been claimed, but his account was instrumental in making it a fabled part of Newton’s biography.

7. He had a brief career as a spy for the French government.

Voltaire struck up a lively correspondence with Frederick the Great in the late 1730s, and he later made several journeys to meet the Prussian monarch in person. Before one of these visits in 1743, Voltaire concocted an ill-advised scheme to use his new position to repair his reputation with the French court. After hatching a deal to serve as a government informant, he wrote several letters to the French giving inside dope on Frederick’s foreign policy and finances.

Voltaire proved a lousy spy, however, and his plan quickly fell apart after Frederick grew suspicious of his motives. The two nevertheless remained close friends—some have even claimed they were lovers—and Voltaire later moved to Prussia in 1750 to take a permanent position in the Frederick’s court. Their relationship finally soured in 1752, after Voltaire made a series of scathing attacks on the head of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

Frederick responded by lambasting Voltaire, and ordered that a satirical pamphlet he had written be publicly burned. Voltaire left the court for good in 1753, supposedly telling a friend, “I was enthusiastic about [Frederick] for 16 years, but he has cured me of this long illness.”

8. He never married or fathered children.

While Voltaire technically died a bachelor, his personal life was a revolving door of mistresses, paramours and long-term lovers. He carried out a famous 16-year affair with the brilliant—and very married—author and scientist Émilie du Châtelet, and later had a committed, though secretive, partnership with his own niece, Marie-Louise Mignot. The two lived as a married couple from the early 1750s until his death, and they even adopted a child in 1760, when they took in a destitute young woman named Marie- Françoise Corneille. Voltaire later paid the dowry for Corneille’s marriage, and often referred to Mignot and himself as her “parents.”

9. He set up a successful watchmaking business in his old age.

While living in Ferney, France, in the 1770s, Voltaire joined with a group of Swiss horologists in starting a watchmaking business at his estate. With the septuagenarian Voltaire acting as manager and financier, the endeavor soon grew into a village-wide industry, and Ferney watches came to rival some of the best in Europe.

“Our watches are very well made,” he once wrote to the French ambassador to the Vatican, “very handsome, very good and cheap.”

Voltaire saw the enterprise as a way to prop up the Ferney economy, and he used his vast network of upper class contacts to find prospective buyers. Among others, he eventually succeeded in peddling his wares to the likes of Catherine the Great of Russia and King Louis XV of France.

10. He continued causing controversy even in death.

Voltaire died in Paris in 1778, just a few months after returning to the city for the first time in 28 years to oversee the production of one of his plays. Over the last few days of his life, Catholic Church officials repeatedly visited Voltaire—a lifelong deist who was often critical of organized religion—in the hope of persuading him to retract his opinions and make a deathbed confession. The great writer was unmoved, and supposedly brushed off the priests by saying, “let me die in peace.”

His refusal meant that he was officially denied a Christian burial, but his friends and family managed to arrange a secret interment in the Champagne region of France before the order became official.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Voltaire Foundation

for Enlightenment studies

Who was Voltaire?

François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), known as Voltaire, was a writer, philosopher, poet, dramatist, historian and polemicist of the French Enlightenment. The diversity of his literary output is rivalled only by its abundance: the edition of his complete works currently nearing completion will comprise over 200 volumes.

‘The age of Voltaire’ has become synonymous with ‘the Enlightenment’, but although Voltaire’s eminence as a philosophe is self-evident, the precise originality of his thought and writings is less easily defined. In this section, you can explore the story of his life , works and legacy .

School of Life: Voltaire – philosopher Alain de Botton has created a short animated video on Voltaire , scripted by Nicholas Cronk: [embedded video]

Born in Paris into a wealthy bourgeois family, he was a brilliant pupil of the Jesuits. His rejection of his father’s attempts to guide him into a career in the law was sealed in 1718, when he invented a new name for himself: ‘de Voltaire’. Voltaire is an anagram of ‘Arouet l(e) j(eune)’ (in the 18th century, i and j , and u and v , were typographically interchangeable). The addition of the aristocratic preposition ‘de’ may be an early sign of his social ambition, but the play on the verb volter , to turn abruptly, evokes a playful or ‘volatile’ quality which fortells the quick style, pervasive humour and irony that make Voltaire such an important figure in the history of the Enlightenment.

In the same year that he coined his new name, Voltaire enjoyed his first major literary success when his tragedy Œdipe was staged by the Comédie Française. Meanwhile he was working on an epic poem which had as its protagonist Henri IV, the much-loved French monarch who brought France’s civil wars to a close, and who, in Voltaire’s treatment, becomes a forerunner of religious toleration: La Ligue (later enlarged to become La Henriade ) was first published in 1723.

VOLTAIRE IN ENGLAND

His reputation as a poet and dramatist was now comfortably established, and he decided to travel to England to oversee the publishing of the definitive edition of La Henriade . His departure for London was precipitated when he unwisely became involved in a humiliating argument with an aristocrat, who had him briefly interned in the Bastille.

Voltaire arrived in London in the autumn of 1726, and what had begun partly as self-imposed exile became a crucially formative period for him. He learned English and mixed with a number of figures prominent in England’s political and cultural life. An old saw has it that Voltaire ‘came to England a poet and left it a philosopher’. In truth, he was a philosopher before coming to England, and it would be more accurate to say that Voltaire came to England a poet and left it a prose writer. Voltaire thought of himself first and foremost as a poet, and during his long life he would never abandon the writing of verse, for which he had a remarkable facility (many of his letters are sprinkled with seemingly spontaneous passages of verse). In England, however, he came into contact with models of prose unlike those to which he was accustomed in France: Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels , for example, which Voltaire read on first publication, or Addison’s Spectator , a periodical he used in order to learn to read English. It is hardly coincidental, therefore, that before returning to France in 1728, Voltaire began writing his first two major essays in prose: a history, the Histoire de Charles XII , and a book about the English, which is now best known under the title Lettres philosophiques , but was first published in English translation (London 1733) as the Letters Concerning the English Nation .

CIREY AND BERLIN

The furore created by the publication in France in 1734 of the Lettres philosophiques led Voltaire to leave Paris and take refuge in the château of his mistress, Mme du Châtelet, at Cirey-en-Champagne. From 1734 until Mme du Châtelet’s death in 1749, this was his haven from the world. During this period, he studied and wrote intensively in a wide variety of areas, including science ( Eléments de la philosophie de Newton , 1738), poetry ( Le Mondain , 1736), drama ( Mahomet , 1741), and fiction ( Zadig , 1747). In the 1740s, Voltaire was briefly on better terms with the court: he was made royal historiographer in 1745, and the following year, after several failed attempts, he was finally elected to the Académie Française. He had turned fifty and was now the leading poet and dramatist of his day; perhaps even Voltaire did not imagine that the works which would make him even more celebrated still lay in the future.

An initially idyllic interlude was provided by Voltaire’s stay at the court of Potsdam (1750-1753), and in 1752 he published both Le Siècle de Louis XIV and Micromégas . Throughout his career, however, Voltaire was prone to involvement in literary quarrels, and his time in Berlin was no exception; his attack on Pierre-Louis de Maupertuis, president of the Berlin Academy, caused Frederick II to lose patience with him. Voltaire left Berlin in a flurry of mutual recriminations, and although these were later forgotten, Voltaire’s dream of having found the ideal enlightened monarch were definitively shattered. His correspondence with Frederick, which had begun in 1736 when the latter was still crown prince, survived, and, after a hiatus, it continued until Voltaire’s death. They corresponded on literary and philosophical matters, and Voltaire sent Frederick many of his works in manuscript. Their exchange of more than seven hundred letters remains as an extraordinary literary achievement in its own right.

GENEVA AND FERNEY

In January 1755, after a period of wandering, Voltaire acquired a property in Geneva which he called ‘Les Délices’. A new and more settled phase now began as, at the age of sixty-one, he became master of his own house for the first time: in a letter of March that year, he wrote that ‘I am finally leading the life of a patriarch’. The Lisbon earthquake of November 1755 may have disturbed his philosophical certainties and caused him to doubt the Leibnizian Optimism which Alexander Pope had helped to popularize, but it did not disturb his new-found personal happiness. His Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne appeared within weeks of the earthquake, and it is revealing that his instant literary response should have been in verse. His prose response to the catastrophe, in Candide , took longer to mature and was published in 1759. In the meantime, he had written articles for the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert, and in 1756 he published his universal history, the Essai sur les mœurs .

In 1757, d’Alembert’s critical article ‘Genève’ in the Encyclopédie had provoked a scandal in that city. Geneva turned out not to be the model republic that Voltaire had imagined or hoped it was, and after a number of tussles with clerical authority, he resolved to leave the city. A return to Paris would not have been welcomed by the government, so he purchased a house and estate at Ferney, where he installed himself in 1760 – on French soil now, but within striking distance of the border. It was in this symbolically marginal position that Voltaire was to live for the rest of his life. Henceforth he would play the part of the seigneur , caring for his estate and even building a church for the villagers: it bears the deist (and immodest) inscription Deo erexit Voltaire (‘Voltaire erected [this] to God’). But this new-found role did not mean that, like Candide, Voltaire had found happiness in cultivating his garden and in ignoring the world beyond. On the contrary, it was in 1760 that Voltaire first issued the rallying cry with which he would henceforth sign many of his letters: Ecrasons l’Infâme (‘Let’s crush the infamous’). The stability of his base at Ferney seems to have given Voltaire the opportunity over the following years to launch and encourage the campaigns which soon made him the most famous writer in Europe.

The Calas affair was a defining moment in this crusade for tolerance. The Huguenot Jean Calas was tortured and broken on the wheel in 1762 after being found guilty, on the basis of dubious evidence, of murdering his son. Voltaire successfully led a determined campaign to clear Calas’s name, writing many letters and publishing a number of works, including Traité sur la tolérance (1763). Other campaigns followed – a successful one to obtain the rehabilitation of another Huguenot family, the Sirvens, accused of having murdered a daughter recently converted to Catholicism, and an unsuccessful one to achieve a pardon for a nineteen-year-old man, La Barre, condemned to be burned at the stake for having committed certain trivial acts of sacrilege (and for having in his possession a copy of Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique ). These struggles brought Voltaire to even greater public prominence, and it in no way diminishes his undoubted determination and courage to say that he obviously relished his new role: in a letter of 1766, he wrote to a friend ‘Oh how I love this philosophy of action and goodwill’.

Although many of Voltaire’s later writings concerned his crusade for tolerance and justice, he continued, to write in a wide variety of forms, from tragedy to biblical criticism, and from satire to short fiction ( L’Ingénu , 1767; Le Taureau blanc , 1773). In February 1778, Voltaire was persuaded by his friends to make a symbolic return to Paris, ostensibly to oversee preparations to stage his latest tragedy, Irène . It was the first time he had set foot in the capital since 1750, and he was received in triumph. A succession of friends called on him, and despite his deteriorating health, he attended a performance of his new play at the Comédie Française, in the course of which his bust was crowned on stage with a laurel wreath. His health did not permit his return to Ferney, and he died in Paris two months later. Even in death, Voltaire, a celebrated amateur actor, seemed to have stage-managed his departure from the scene so as to gain maximum publicity.

Voltaire and the Enlightenment

In terms of the history of ideas, Voltaire’s single most important achievement was to have helped in the 1730s to introduce the thought of Newton and Locke to France (and so to the rest of the Continent). This achievement is, as Jonathan Israel has recently shown, hardly as radical as has sometimes been thought: the English thinkers in question served essentially as a deistic bulwark against the more radical (atheistic) currents of thought in the Spinozist tradition. Voltaire’s deist beliefs, reiterated throughout his life, came to appear increasingly outmoded and defensive as he grew older and as he became more and more exercised by the spread of atheism. Voltaire’s failure to produce an original philosophy was, in a sense, counterbalanced by his deliberate cultivation of a philosophy of action; his ‘common sense’ crusade against superstition and prejudice and in favour of religious toleration was his single greatest contribution to the progress of Enlightenment. ‘Rousseau writes for writing’s sake’, he declared in a letter of 1767, ‘I write to act.’

It was therefore Voltaire’s literary and rhetorical contributions to the Enlightenment which were truly unique. Interested neither in music (like Rousseau) nor in art (like Diderot), Voltaire was fundamentally a man of language. Through force of style, through skilful choice of literary genre, and through the accomplished manipulation of the book market, he found means of popularizing and promulgating ideas which until then had generally been clandestine. The range of his writing is immense, embracing virtually every genre. In verse, he wrote in every form – epic poetry, ode, satire and epistle, and even occasional and light verse; his drama, also written in verse, includes both comedies and tragedies (although the tragedies have not survived in the modern theatre, many live on in the opera, as, for example, Rossini’s Semiramide and Tancredi ).

It is above all the prose works with which modern readers are familiar, and again the writings cover a wide spectrum: histories, polemical satires, pamphlets of all types, dialogues, short fictions or contes , and letters both real and fictive. The conspicuous absentee from this list is the novel, a genre which, like the prose drame , Voltaire thought base and trivial. To understand the strength of his dislike for these ‘new’ genres, we need to remember that Voltaire was a product of the late seventeenth century, the moment of the Quarrel between Ancients and Moderns, and this literary debate continued to influence his aesthetic views all through his life. Controversial religious and political views were often expressed in the literary forms (classical tragedy, the verse satire) perfected in the seventeenth century; the ‘conservatism’ of these forms seems, to modern readers at least, to compromise the content, though this apparent traditionalism may in fact have helped Voltaire mask the originality of his enterprise: it is at least arguable that in a work such as Zaïre (1732), the form of the classical tragedy made its ideas of religious toleration more palatable.

Yet this would also be a simplification, for notwithstanding his apparent literary conservatism, Voltaire was in fact a relentless reformer and experimenter with literary genres, innovative almost despite himself, particularly in the domain of prose. Although he never turned his back on verse drama and philosophical poetry, he experimented with different forms of historical writing and tried his hand at different styles of prose fiction. Above all, he seems to have discovered late in his career the satirical and polemical uses of the fragment, notably in his alphabetic works, the Dictionnaire philosophique portatif (1764), containing 73 articles in its first edition, and the Questions sur l’Encyclopédie (1770-1772). The latter work, whose first edition contained 423 articles in nine octavo volumes, is a vast and challenging compendium of his thought and ranks among Voltaire’s unrecognized masterpieces. When he died, Voltaire was working on what would have been his third ‘philosophical’ dictionary, L’Opinion en alphabet .

Voltaire’s ironic, fast-moving, deceptively simple style makes him one of the greatest stylists of the French language. All his life, Voltaire loved to act in his own plays, and this fondness for role-playing carried through into all his writings. He used something like 175 different pseudonyms in the course of his career, and his writing is characterized by a proliferation of different personae and voices. The reader is constantly drawn into dialogue – by a footnote which contradicts the text, or by one voice in the text which argues against another. The use of the mask is so relentless and the presence of humour, irony, and satire so pervasive that the reader has finally no idea of where the ‘real’ Voltaire is. His autobiographical writings are few and entirely unrevealing: as the title of his Commentaire historique sur les Œuvres de l’auteur de la Henriade suggests, it is his writings alone which constitute their author’s identity.

In fact we rarely know with certainty what Voltaire truly thought or believed; what mattered to him was the impact of what he wrote. The great crusades of the 1760s taught him to appreciate the importance of public opinion, and in popularizing the clandestine ideas of the early part of the century he played the role of the journalist. He may have been old-fashioned in his nostalgia for the classicism of the previous century, but he was wholly of his day in his consummate understanding of the medium of publishing. He manipulated the book trade to achieve maximum publicity for his ideas, and he well understood the importance of what he called ‘the portable’. In 1766, Voltaire wrote to d’Alembert: ‘Twenty in-folio volumes will never cause a revolution; it’s the little portable books at thirty sous which are to be feared.’

Voltaire was also modern in the way he invented himself by fashioning a public image out of his adopted name. As the patriarch of Ferney, he turned himself into an institution whose fame reached across Europe. As an engaged and militant intellectual, he stood at the beginning of a French tradition which looked forward to Emile Zola and to Jean-Paul Sartre, and in modern republican France his name stands as a cultural icon, a symbol of rationalism and the defence of tolerance. Voltaire was a man of paradoxes: the bourgeois who as de Voltaire gave himself aristocratic pretensions, but who as plain Voltaire later became a hero of the Revolution; the conservative in aesthetic matters who appeared as a radical in religious and political issues. He was, above all, the master ironist, who, perhaps more than any other writer, gave to the Enlightenment its characteristic and defining tone of voice.

– N. E. Cronk

It has been estimated that, in a career which stretched over sixty years, Voltaire’s extant writings ran to some fifteen million words: everything concerning the Œuvre seems larger than life, and it is hard to make any simple assessment of it. ‘Complete’ editions appeared in Voltaire’s lifetime; the last, published by Cramer in Geneva in 1775, ran to forty volumes (the so-called édition encadrée ). The first complete edition of Voltaire’s writings after his death, known as the Kehl edition, was published on the eve of the Revolution (1785-1789) in seventy octavo volumes (there was also a duodecimo edition in ninety-two volumes). Many complete editions followed in the nineteenth century, culminating in the Moland edition (1877-1883) in fifty-two volumes, which remains – pending the completion of the Oxford edition – the standard edition of reference.

Theodore Besterman’s ‘definitive’ edition of Voltaire’s correspondence (1968-1977) includes more than 15,000 letters, but these surviving letters must represent only a fraction of the total number written by Voltaire in his lifetime, probably in excess of 40,000. This edition is part of the larger Complete Works of Voltaire , a complete and critical edition of all Voltaire’s writings currently being published by the Voltaire Foundation in Oxford; when complete, it will exceed two hundred volumes.

The list How to quote Voltaire gives the best available edition for each text that Voltaire wrote. A reliable, searchable version of his works is available on-line on TOUT VOLTAIRE .

We use cookies to help give you the best experience on our website. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, we assume you agree to this. Please read our cookie policy to find out more. more information Accept

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this.

- Art History

- U.S. History

Voltaire was one of the great French writers and philosophers of the Enlightenment Age. Much of his writing was punctuated with a sharp sense of wit, which was one of the reasons he was popular during his time and beyond. Voltaire was also a very versatile writer having been able to produce works of poetry, history, long form fiction novels, nonfiction essays, and even scientific tomes.

Voltaire was also known for his controversies, particularly in areas related to religion. He was not a proponent of the Catholic Church and he routinely criticized it. Like many other philosophers of the Enlightenment, Voltaire professed a belief in the need for a separation of church and state.

There were very harsh censorship laws in existence at the time of Voltaire and he constantly challenged those laws in his writings. His iconoclastic writings have survived the test of time and he remains a philosopher many read and study in the modern era.

Voltaire’s Early Years

Voltaire was born on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. His birth name was François-Marie Arouet. His father was a lawyer and his mother was from a family of nobles. Voltaire attended the Collège Louis-le-Grand where he was educated by Jesuits for seven years. His father wanted his son to become a lawyer, but Voltaire wanted to be a writer. As history shows us, he did become a writer and went on to publish upwards of 2,000 works.

He first started using the fictitious name Voltaire around 1718. The name was derived from an anagram of the Latin spelling of his real last name. It would seem he used the pen name as a means of hiding his identity from his family.

His Secret Writing Career

Voltaire told his father that he was working as a notary in Paris when he was really spending most of his time writing poetry. His father was furious when he found out and forced Voltaire to enter law school. The young philosopher continued to write even when after he was sent to work in the embassy at the Netherlands. He eventually lost his job for having an affair with a young woman. Eventually, he returned to Paris where he continued writing. He had a large number of readers and even those in the aristocracy spoke highly of his muse.

Not everyone was fond of what he had written. After publishing something satirical about Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, Voltaire ended up spending 11 months in prison. Not to be deterred, Voltaire continued to write and even produce plays.

The Work of Voltaire

Voltaire wrote a great many philosophical treatises on religion. He attacked flaws he saw in modern religious theories. He was a deist who constantly questioned the role of faith. Voltaire did not like organized religion and he felt no particular faith was required to believe in God. As a proponent of natural law, he felt morality can derive from sources outside of religion.

Voltaire was most definitely not in favor of suppressing religion though. In reality, he was a great believer in tolerance towards religion.

Voltaire might be considered someone who believed in the notion of a philosopher king. Democracy was not something he was a huge fan of because he felt too many of the masses simply were not capable of making good decisions. He was not exactly a believer in monarchs or politicians as he saw them as routinely being too corrupt and self-serving to trust. Voltaire assumed that an enlightened monarch might be the one person best served to rule a nation.

Final Days of Voltaire

At the age of 83, Voltaire returned to Paris after a 20 year absence. He was returning home in order to see a play. The journey was too much for him and he passed away on May 30, 1778, after falling quite ill.

Newest Additions

- Malala Yousafzai

- Greta Thunberg

- Frederick Douglass

- Wangari Maathai

Copyright © 2020 · Totallyhistory.com · All Rights Reserved. | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Dec 5, 2024 · “Voltaire” is the pen name under which French author-philosopher François-Marie Arouet published a number of books and pamphlets in the 18th century. He was a key figure in the European intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. Voltaire was quite controversial in his day, in no small part because of the critical nature of his work.

Aug 9, 2023 · Early Life. Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet to a prosperous family on November 21, 1694, in Paris. He was the youngest of five children born to François Arouet and Marie Marguerite d'Aumart.

Voltaire was a versatile and prolific writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, histories, and even scientific expositions. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and 2,000 books and pamphlets. [7] Voltaire was one of the first authors to become renowned and commercially successful internationally.

Early years Voltaire was born as François Marie Arouet, perhaps on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. He was the youngest of the three surviving children of François Arouet and Marie Marguerite Daumand, although Voltaire claimed to be the "bastard [born out of wedlock] of Rochebrune," a minor poet and songwriter.

Nov 23, 2023 · Voltaire pioneered a new form of literature, the conte, a short and imaginative flight of fancy similar to ancient oral storytelling. The conte genre allows a writer to present serious ideas in an exotic or fanciful setting that both entertains the reader and sets them thinking. Voltaire's masterpiece in this new style was Candide, published in ...

Aug 16, 2020 · Early Life . Voltaire was the fifth child and fourth son of François Arouet and his wife Marie Marguerite Daumard. The Arouet family had already lost two sons, Armand-François and Robert, in infancy, and Voltaire (then François-Marie) was nine years younger than his surviving brother, Armand, and seven years younger than his sole sister, Marguerite-Catherine.

Voltaire Biography Voltaire (21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778) was a French writer, essayist, and philosopher – he was known for his wit, satire, and defence of civil liberties. He sought to defend freedom of religious and political thought and played a major role in the Enlightenment period of the eighteenth century.

Nov 21, 2014 · Voltaire wasn’t the original source for the story of the “Eureka!” moment, as has often been claimed, but his account was instrumental in making it a fabled part of Newton’s biography. 7.

Voltaire arrived in London in the autumn of 1726, and what had begun partly as self-imposed exile became a crucially formative period for him. He learned English and mixed with a number of figures prominent in England’s political and cultural life. An old saw has it that Voltaire ‘came to England a poet and left it a philosopher’.

Voltaire was born on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. His birth name was François-Marie Arouet. His father was a lawyer and his mother was from a family of nobles. Voltaire attended the Collège Louis-le-Grand where he was educated by Jesuits for seven years. His father wanted his son to become a lawyer, but Voltaire wanted to be a writer.