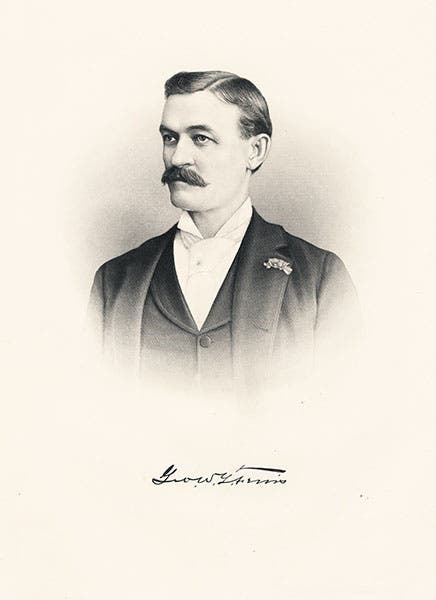

George Washington Gale Ferris

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. was born on February 14, 1859, in Galesburg, Illinois. After spending his childhood with his family in Carson City, Nevada, Ferris attended the California Military Academy and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York. He married Margaret Ann Beatty from Canton, Ohio. Ferris's career as a civil engineer was rewarding. His success skyrocketed when he created the Ferris wheel, thus solidifying his reputation. Ferris died from typhoid fever on November 21, 1896, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he spent most of his life.

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. was born on February 14, 1859, in Galesburg, Illinois. Silvanus Ferris, his grandfather, and Reverend George W. Gale founded this village in central Illinois, according to Judith Adams-Volpe in the American National Biography . Ferris was the son of George Washington Gale Ferris Sr. and Martha Edgerton Hyde Ferris; he grew up on a farm with his four sisters and two brothers. In 1864, when Ferris was five-years-old, the family decided to sell the farm and move west to San Jose, California. However, when they arrived in Carson City, Nevada, they were unable to travel farther because money was not worth as much due to inflation caused by the Civil War. California was out of reach at the time, so the Ferris family settled on a ranch near Carson City.

After spending nine years helping his father on the ranch, Ferris attended the California Military Academy in Oakland, California, in 1873. After graduation in 1876, Ferris attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. During his college career, Ferris found time to join clubs and extracurricular activities, such as the glee club, football, and baseball. Ferris did not take his education as seriously as many would think because he had to retake particular courses in order to graduate. Nevertheless, Ferris buckled down and received his degree in civil engineering in February 1881.

With a degree under his belt, Ferris was ready to find work as soon as possible. His first job was with a railroad constructing office in New York City; he worked under General J.H. Ledlie, a famous contractor who taught Ferris the ropes of real life engineering. During the first year working for the company Ferris traveled to West Virginia to locate a reasonable route for the Baltimore, Cincinnati & Western railway to run through the Elk River Valley. The railway had to consist of 78 miles for the project to be completed correctly. Ferris was also assigned to locate a route for a narrow-gauge track in Putnam County, New York.

After working for one year under General J.H. Ledlie, Ferris became a professional civil engineer and then a general manager for the Queen City Mining Company in West Virginia in 1882. Ferris designed and built a coal trestle, a tower used to support a bridge, over the Kanawha River. After the bridge project was completed, Ferris was assigned to build three 1,800-foot tunnels as well. Ferris only spent a year working for the Queen City Mining Company because in 1883 the company closed. Fortunately, Ferris did not lose work due to the company's closing; he became an assistant engineer for the Louisville Bridge & Iron Company in Louisville, Kentucky. During this time, Ferris earned a reputation "for concrete work under heavy pressure in pneumatic caissons" while he worked on the Henderson Bridge located across the Ohio River. He also earned a reputation as "an astute businessman" since he became an expert on large steel structures during the mid-1880s. Ferris then transferred to the Kentucky and Indiana Bridge Company of Louisville in 1885 due to health hazards from working with the previous company. Ferris was in charge of testing and inspecting the steel and iron bought from Pittsburgh steel mills, as stated in the Dictionary of American Biography .

Even though the civil engineering profession consumed most of his time and energy, Ferris found the time to enhance his social life. He fell in love with a woman from Canton, Ohio, and in 1886 he married Margaret Ann Beatty. The happily married couple moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Ferris continued to pursue his dream of becoming a successful engineer as he established the firm of G.W.G. Ferris & Company, Inspecting Engineers along with James C. Hallsted. The company soon spread to other major cities, including New York and Chicago. Ferris began to give his full attention to the promotion and financing of large-scale engineering projects. Ferris founded another firm, Ferris, Kaufman and Company, in 1890, and also kept close ties with his original firm.

The new firm focused on constructing major bridges across the Ohio River at Wheeling, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh. Ferris earned a name for himself during the early years of his career as an engineer. However, he did not realize the fame and recognition he was about to receive in the next few years of his life. In 1892, the chief of construction for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Daniel H. Burnham, challenged the prominent civil engineers of the United States to create a structure that would become a rival to the Eiffel Tower, constructed at the recent World's Fair in Paris. As Michael Valenti stated in Mechanical Engineering , the structure had to be original, daring, and unique. Ferris immediately began thinking of a creation that would prove worthy of such a description. That very evening he sketched a revolving "observation wheel" on a piece of paper and planned to present his idea to the committee the next day. Ferris imagined two large, parallel circles connected with struts that revolved around a steel axis. The wheel would lift passengers in railroad-style cars and move them in a circular rotation. The committee found the idea unrealistic and superficial due to its size and purpose. Ferris was still determined to find a way to design and build this wheel.

After convincing several engineers to sponsor his structure and finding investors to pay $400,000 for construction, the committee finally approved Ferris' idea on November 29, 1892. His partner, William F. Gronau, was assigned the design detail and construction responsibility, while Ferris took on the responsibility to secure the concession. The United States was going through a period of depression in 1893, so financing the entire project was extremely difficult. Ferris also had to contact several companies in the East and Midwest for the production of parts needed to build the wheel. Many components were manufactured in Cleveland and Youngstown, Ohio, and in Pittsburgh and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. These parts were then loaded onto 150 railroad cars and shipped to Chicago where the excavations were under way. The major task Ferris had to conquer in January 1893 was the pouring of the concrete footings. With temperatures below freezing, the crews dug as quickly as possible. At about 35 feet down the cubic blocks of concrete were poured while steam was used to keep them from freezing.

After the foundation was built, the two parallel towers were next on the agenda. They were built out of vertical posts and horizontal braces that were supported with crisscrossed rolled-metal rods. Plate-iron girders were placed on the bottom of the wheel for more strength and support. Upon completion of the towers, the main component, the wheel, needed to be put into place. The 45-ton axle was fastened to the two towers with spokes, beams, and iron rods for safety and stability. The addition to the monstrous wheel was the thousand-horsepower horizontal coal-fired steam engine needed for rotation. A Westinghouse air brake was also installed in case the wheel needed to stop immediately. The finished product rose to a height of about 264 feet with a circumference of about 825 feet; the 4,000 ton ride carried 36 passenger cars that could hold more than 2,000 people at a time. Ferris's wheel proved able to withstand the vicious Chicago winds with its strength and stability, according to the American National Biography . Ferris designed and built a structure that would never be forgotten.

On June 16, 1893, the Ferris wheel was open to the public at the Chicago Exposition. According to the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette , Mrs. Ferris made a toast to her husband while in one of the passenger cars on the Ferris wheel. She toasted the health of her husband and the success of the Ferris wheel. At first, many visitors were afraid to ride on such an enormous wheel, but the fear soon subsided as more passengers ventured into the nicely designed passenger cars. For 19 weeks the Ferris wheel made over 10,000 revolutions without incident and carried more than 1.5 million passengers who paid 50 cents for a 20-minute ride. During this time, the Ferris wheel brought in over $750,000 in profit for the Chicago Exposition, according to the Inventor of the Week Archive . Once the Chicago Exposition closed, the wheel made its final appearance in St. Louis, Missouri, at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Finally, May 11, 1906, the Ferris wheel was dynamited as the novelty came to an end. Ferris did not experience the destruction of his marvelous creation because he passed away on November 21, 1896, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, without his wife by his side. She previously returned to her hometown in Canton, Ohio, when their childless marriage came to an end. The American National Biography stated that Ferris died from typhoid fever; however, complications from kidney disease could have played a role in the cause of his death. Suicide also seemed like a rational possibility because Ferris was alone and bankrupt at the time of his death. Some believe his overwhelming sadness was the driving force to take his own life.

According to Judith Adams-Volpe from the American National Biography , Ferris' partners Gustave Kaufman and D.W. McNaugher gave a praiseworthy eulogy of Ferris; they said, "He was always bright, hopeful and full of anticipation of good results from all the ventures he had on hand. These feelings he could always impart to whomever he addressed in a most wonderful degree, and therein laid the key not of his success. In most darkened and troubled times, he was ever looking for the sunshine soon to come, he died a martyr to his ambition for fame and prominence." Ferris earned a reputation as one of the most daring entrepreneurs, optimists, and engineers of the nineteenth century in the United States. The Ferris wheel brightened the horizon for new technologies and inventions that could be possible with imagination and determination. "The feverish pace of his engineering projects and businesses mirrored the accomplishments of U.S. engineers who created a civilization for a new country," Adams-Volpe stated. Ferris became a subject of interest to many people, especially Erik Larson who based his book, The Devil in the White City , on the Chicago's World Fair in 1893. Larson wrote about the true story of the architect who created the World Fair and the serial killer who murdered his victims in the fair. Throughout the suspenseful book the Ferris wheel was one of the major attractions at the World's Fair.

Today most amusement parks and carnivals around the world have smaller versions of Ferris wheels as well as more complex versions, such as the London Eye and the Vienna Prater wheel. Even though these amusement parks have new improved structures, such as roller coasters, the Ferris wheel will always be a legendary part of each and every park. Ferris left behind an unforgotten legacy after he passed away. His success as an engineer and as an inventor is now admired and appreciated as people wait in line to ride the legendary Ferris wheel.

- "266 Feet in Air." Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette 17 June 1893.

- Adams-Volpe, Judith. "Ferris, George Washington Gale, Jr." American National Biography Online . Jan. 2002. 1 Nov. 2006. < >http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-02643.html> .

- "Bombs and Bones: A Ferris Family Tree." Dictionary of American Biography . 1 Nov. 2006. 2006. < >http://www.ferristree.com/george_washington_gale_ferris.htm> .

- "George Ferris: The Ferris Wheel." Inventor of the Week Archive . May 1999. 1 Nov. 2006. < >http://web.mit.edu/INVENT/iow/ferris.html> .

- Larson, Erik. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America . New York: Random House, 2003.

- Valenti, Michael. "100 Years and Still Going Around in Circles." Mechanical Engineering 115:6 (1993): 70-7.

For More Information:

- Anderson, Norman D. Ferris Wheels: An Illustrated History . Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1992.

Photo Credit: " George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., inventor of theˇFerris wheel. " before 1896. Portrait. Licensed under Public Domain . cropped to 4x3. Source: Wikimedia.

Join our email list and be the first to learn about new programs, events, and collections updates!

Monday, December 16, 2024

Open today 4 PM - 11 PM

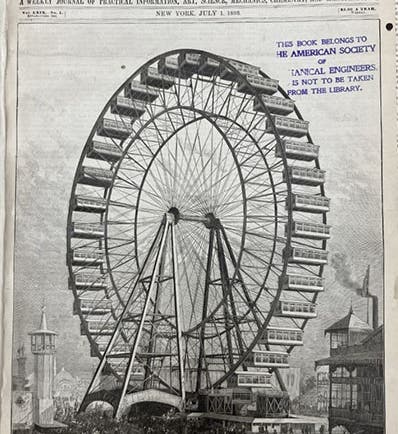

Opening of the Ferris Wheel at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, front cover of Scientific American , July 1, 1893 (Linda Hall Library)

George Washington Ferris

Scientist of the day - george washington ferris.

George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., an American engineer, was born Feb. 14, 1859, in Illinois. After a childhood in Nevada, he attended school in California, and then studied engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in New York, an institution that turned out many of American's top engineers at the time. Ferris was interested in the engineering potential of structural steel, and he established a company in Pittsburgh to test structural steel and to build bridges, starting with one over the Monongahela River at 6th St. in Pittsburgh (since demolished, like all of the Pittsburgh river bridges of the 1880s and 1890s). He was apparently very good at his job and a genius with steel.

Portrait of George Washington Ferris, photograph, undated but ca 1893, Chicago History Museum (googleusercontent.com)

In 1891, the World’s Columbian Exposition was getting ready to open on the Midway in Chicago in the spring of 1893, and the Director felt that they lacked a “wow factor”, like the Eiffel tower that made its debut at the Paris Exposition in 1889. So he issued a challenge to the nation's engineers: what can we build at our Exposition to trump the French? There were not interested in a tower, even if taller. Ferris had apparently already had an idea for a vertical wheel to carry sightseers up into the air, but now he began to think more grandly, and he proposed a gigantic version of his wheel to the fair organizers. There were initial questions about safety, and whether it would work, but Ferris was persuasive, and apparently his idea was better that the proposals of anyone else, and his idea was finally approved. However, he would have to bear construction costs himself, and even worse, it was now mid-December 1892, and the exposition was set to open four months later.

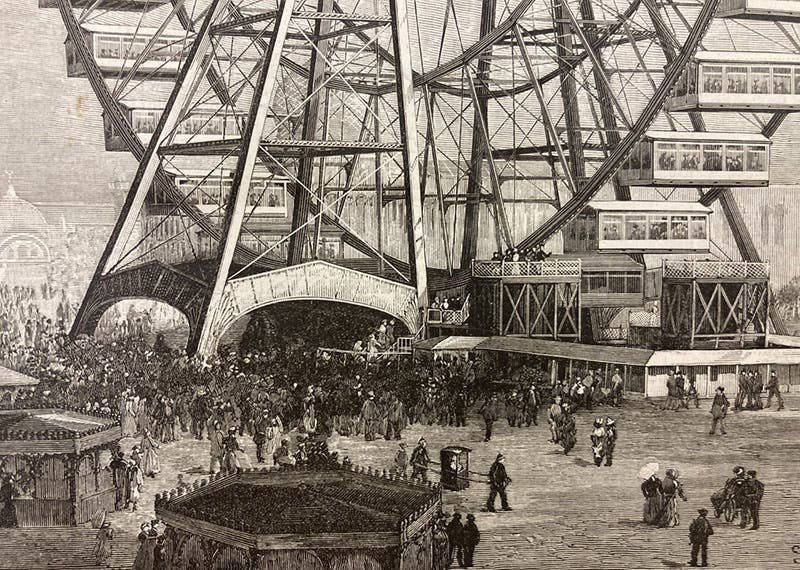

Detail of first image, showing crowds on the Midway at the foot of the Ferris Wheel on opening day, June 11, 1893 (Linda Hall Library)

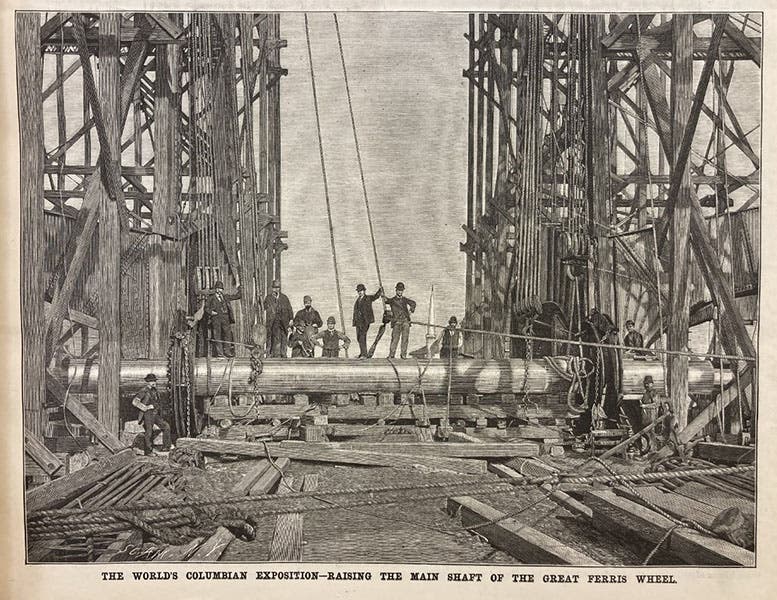

Incredibly, Ferris raised funds, ordered steel, built foundations, and had the wheel up and running by June 11, 1893, not quite in time for the opening, but still a remarkable feat. Equally amazing, since there was no precedent for such a gigantic wheel, it worked perfectly – there were no accidents of any kind. The wheel was what is called a tension wheel, which means it was held together by tension wires, just like a bicycle wheel. The largest tension wheel that had been built to that time was 30 feet across. Ferris’s wheel was 250 feet across, carried 36 gondolas, each of which had 40 seats but could carry 60 passengers, and the riders at the top were 264 feet off the ground and could see further than anyone in Chicgo had ever seen before. The main axle was 45 feet long and weighed 45 tons and was the largest piece of forged steel ever fabricated in this country.

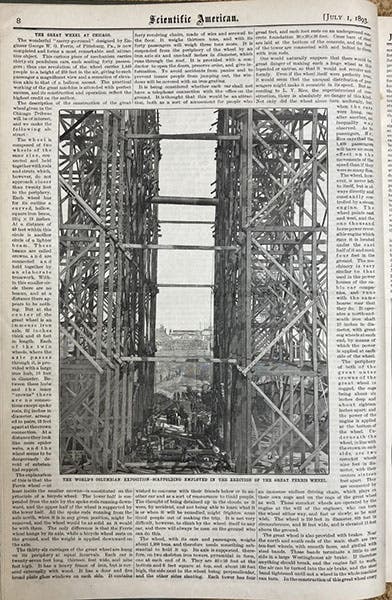

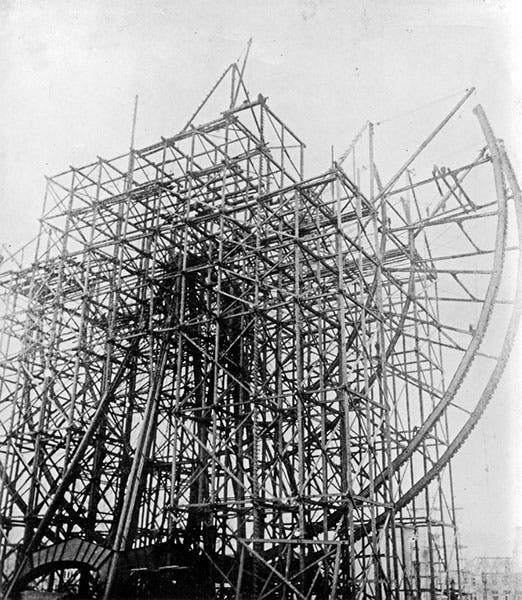

Wooden scaffolding for erecting the Ferris Wheel in Chicago, Scientific American, July 1, 1893 (Linda Hall Library)

Building the Ferris Wheel for Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition, photograph, April, 1893 (chicagology.com)

The Ferris wheel drew immense crowds for the six months of the fair, carrying 1.5 million passengers and pulling in $750,000 at fifty cents a pop. Ferris became America’s most famous engineer almost overnight, and he was only 34 years old. But it was one of the few bright spots in the rest of his life. There was considerable contentiousness between the Exposition committee and Ferris's company as to how profits were to be distributed, once receipts paid off the cost of construction (which was about $364,000), and Ferris came out of the lawsuits much poorer than he expected. He was certainly not happy when Chicago dismantled the Wheel after the fair closed, although it was re-erected in Lincoln Park as a sight-seeing attraction. Apparently, Chicagoans had a more short-sighted view of their monuments than Parisians, who allowed the Eiffel Tower to stand right where it was built. Ferris’s health had suffered during the ordeal of construction and went further downhill during the subsequent litigation. Then his wife left him. And in 1896, he came down with typhoid fever; he was hospitalized, and breathed his last on Nov. 22, 1896. He was 37 years old.

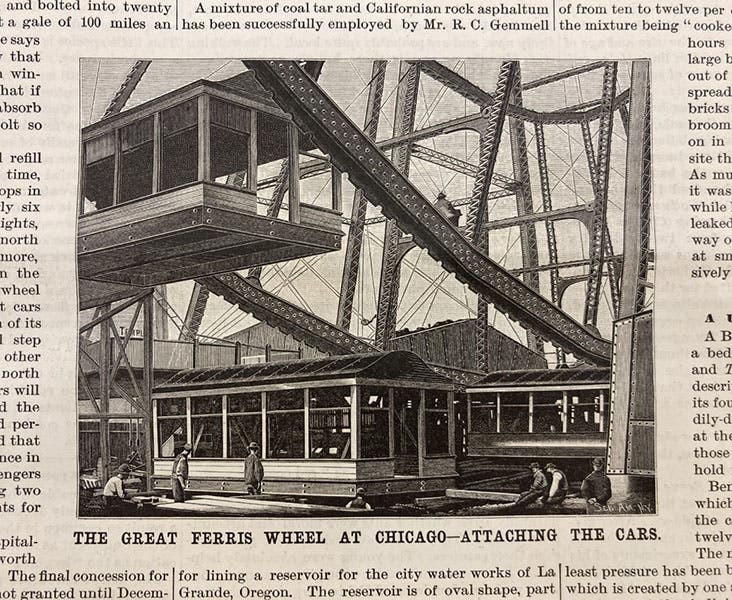

Gondolas waiting to be attached to the Ferris Wheel in Chicago, Scientific American, July 1, 1893 (Linda Hall Library)

Ferris’s wheel had a little more life in it. It wasn’t bringing in much revenue in its Lincoln Park location, since the park did not have a liquor license, so when some entrepreneurs wanted to buy it, take it down, and ship it to St. Louis, the city was happy to bid the wheel adieu. It was re-erected in St. Louis for the Pan-American Exposition of 1904. When that fair was over, the wheel was brought down with TNT, collapsing into a mass of scrambled steel and sold for scrap. It was an ignominious end to a marvel of civil engineering.

The 45-foot, 45-ton forged steel shaft on which the Ferris Wheel rotated, Scientific American, July 1, 1893 (Linda Hall Library)

The original wheel may have perished, but as everyone knows, the idea of the Ferris Wheel caught on, and thousands were built, smaller and more portable, for county fairs across the country. And they have always been called "Ferris wheels”. Ferris has achieved some kind of immortality after all, although one must note that the two largest modern Ferris wheels, the only ones to exceed the scale of the 1893 wheel, have dropped the name Ferris, and are called "The Eye” (London), and “The Flyer” (Singapore).

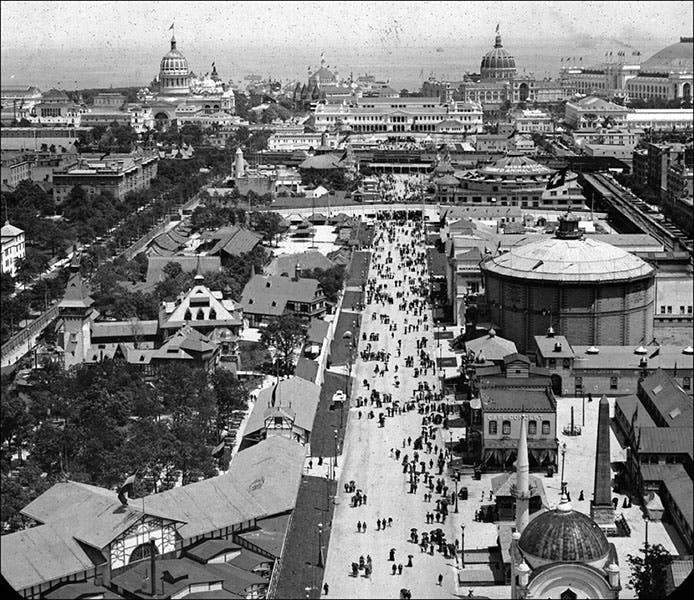

A view of the Midway at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, a photograph taken from the top of the wheel, 1893 (chicagology.com)

Most of our images were drawn from a Scientific American article in their July 1, 1893 issue, just two weeks after the Ferris Wheel was inaugurated. The front cover ( first image ) showed the scene at the opening; we also show a detail of that cover, showing the crowds and the gondolas at the bottom of the wheel. Two of our images, a photo of construction in process ( fifth image ), and photo of the Midway from the top of the wheel ( eighth and last image ), came from a useful website called “ Chicagology ,” with many images of the 1893 wheel. There also survives a brief 50-second film of the wheel in motion, made in 1896 at the Lincoln Park location.

Recently, it was announced that the 45-ton main shaft has been located by a metal detectorist, in St. Louis, buried underground, not far from where the Ferris Wheel stood in 1904. Or at least he detected a 45-foot-long metal object buried there. As it lies under a road, it may not be excavated anytime soon. But if it hasn’t completely rusted away, it might be nice to dig it up someday and give George Ferris a physical monument that we can walk up to and touch.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to [email protected] .

Library Hours

Monday - Friday 10 AM - 5 PM

IMAGES

VIDEO