BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on academic performance: a comparative analysis of face-to face and online assessment.

- 1 Department of Cognitive Sciences, Psychology, Education and Cultural Studies, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

- 2 Department of Philosophy and Communication, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 3 Department of Psychology and Neurosciences, Leibniz Research Centre for Working Environment and Human Factors at TU Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany

- 4 Bielefeld University, University Hospital OWL, Protestant Hospital of Bethel Foundation, University Clinic of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Clinic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Bielefeld, Germany

- 5 Dipartimento di Psicologia “Renzo Canestrari”, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Cesena, Italy

- 6 Neuropsychology and Cognitive Neuroscience Research Center (CINPSI Neurocog), Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile

Introduction: Survey studies yield mixed results on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic performance, with limited direct evidence available.

Methodology: Using the academic platform from the Italian university system, a large-scale archival study involving 30,731 students and 829 examiners encompassing a total of 246,416 exams (oral tests only) to scrutinize the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the likelihood of passing exams was conducted. Examination data were collected both in face-to-face and online formats during the pandemic. In the pre-pandemic period, only face-to-face data were accessible.

Results: In face-to-face examination, we observed a lower probability of passing exams during the pandemic as opposed to pre-pandemic periods. Notably, during the pandemic we found an increased chance of passing exams conducted through online platforms compared to face-to-face assessments.

Discussion and conclusions: These findings provide the first direct evidence of an adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic performance. Furthermore, the results align with prior survey studies underscoring that using telematics platforms to evaluate students' performance increases the probability of exam success. This research significantly contributes to ongoing efforts aimed to comprehend how lockdowns and the widespread use of online platforms impact academic assessment processes.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced nations to undergo significant restructuring across economic, health and educational systems. Recent psychological research, spanning the past 3 years, has started to illuminate the impact of prolonged exposure to a pandemic along with associated lockdowns and home confinement on cognitive and affective processing (e.g., Diotaiuti et al., 2021 , 2023 ; Fiorenzato et al., 2021 ; Wilke et al., 2021 ; Gewalt et al., 2022 ; Rania et al., 2022 ). For example, Fiorenzato et al. (2021) , documented an increase in the severity and prevalence of conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, abnormal sleep, appetite changes, decreased libido, and health-related anxiety in the pandemic. On the cognitive level, the authors reported a paradoxical improvement in memory, compared to pre-lockdown. However, the authors of this study reported subjective complaints of the participants with respect to daily activities involving attention, temporal orientation, and executive functions. This highlights that the effects of the pandemic on mental processes extend to both affective and cognitive dimensions.

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed education systems to unprecedented challenges, with a sudden shift of classroom-based pedagogics to distant learning approaches ( Aldossari and Chaudhry, 2021 ). This transition from face-to-face to virtual classes has resulted in a diverse spectrum of educational models: on the one hand, some professors replicated their in-person classes through videoconferencing, while, on the other hand, others undertook a comprehensive overhaul of their teaching plans to align methodological and evaluative strategies with the demands of the new context ( Fardoun et al., 2020 ; Ramos-Pla et al., 2021 ). For instance, there's an observable trend of increasing collaborative work ( Ramos-Pla et al., 2022 ), which enhances professor-student interactions—a critical predictor of students' perceived quality of teaching ( del Arco et al., 2021 ). In response to this paradigm shift, training centers across various universities adapted their programs to facilitate the continuous learning of professors. However, these educators faced challenges, expressing concerns about the time constraints in assimilating new knowledge into their teaching practices and the complexities of online evaluations ( Ramos-Pla et al., 2021 ). Moreover, other studies underscored students' difficulties in following online courses, particularly those without personal devices or sharing them with other family members ( Ramos-Pla et al., 2023 ).

In the present study, we focused on academic assessment, a pivotal sector significantly impacted by the pandemic ( Onyema et al., 2020 ; Rashid and Yadav, 2020 ; Estrada Guillén et al., 2022 ; Gewalt et al., 2022 ). This sector witnessed an extensive adoption of telematic technologies and was a dynamic response to ensure the continuity of educational services, including university services.

To the best of our knowledge, the existing literature (e.g., Mahdy, 2020 ; Radu et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ; Akin-Odanye et al., 2021 ; Andersen et al., 2022 ; Appleby et al., 2022 ; Hadwin et al., 2022 ) exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic performance is based on conventional survey research methodology. For instance, Mahdy (2020) examined the academic performance of veterinary medical students during the pandemic by collecting their opinions via an online Google form questionnaire. The author pointed out that while online education offers an opportunity for self-study, the main pandemic-related challenge in veterinary medical science is how to give practical lessons. Moreover, the study by Estrada Guillén et al. (2022) identified a connection between emotional intelligence and resilience to pandemics, which was associated with better academic performance. This can help to explain the mixed results provided by the literature in the field (e.g., Gonzalez et al., 2020 ; Giusti et al., 2021 ; Keržič et al., 2021 ).

Traditional–internet-based survey panels are characterized by several limitations such as response or sampling biases, desirability biases, and memory recall biases ( Andrade, 2020 ). Moreover, the sampled data might not be representative of the actual population ( Hays et al., 2015 ), potentially yielding biased results.

In the current study, we aimed to overcome such limitations by examining actual data recorded and archived within our university multifunction academic (online) platform to answer a series of outstanding questions not addressable via survey studies. This platform serves as a comprehensive teaching management computer system, providing students and professors with a dedicated space to oversee exam registration, grade management, and participation in university initiatives. The wealth of information available through this platform includes details about the scheduling of all exams, and the outcomes of each student evaluated within our university. This dataset thus provides a more reliable and accurate picture of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic achievement compared to survey studies. Furthermore, these actual data serve as a robust alternative to subjective survey measures, which are susceptible to biases, including those stemming from social expectations. Finally, this dataset allowed us to explore whether and how the mode of examination (face-to-face vs. online platform) during the pandemic influences its impact.

Our focus was directed to data spanning the period between January 2019 and October 2021. This specific time frame facilitated a comparative analysis, allowing us to discern any differences between “in-person” and “online” examinations, both in the period just before and during the pandemic. Additional details are offered in the Methods section.

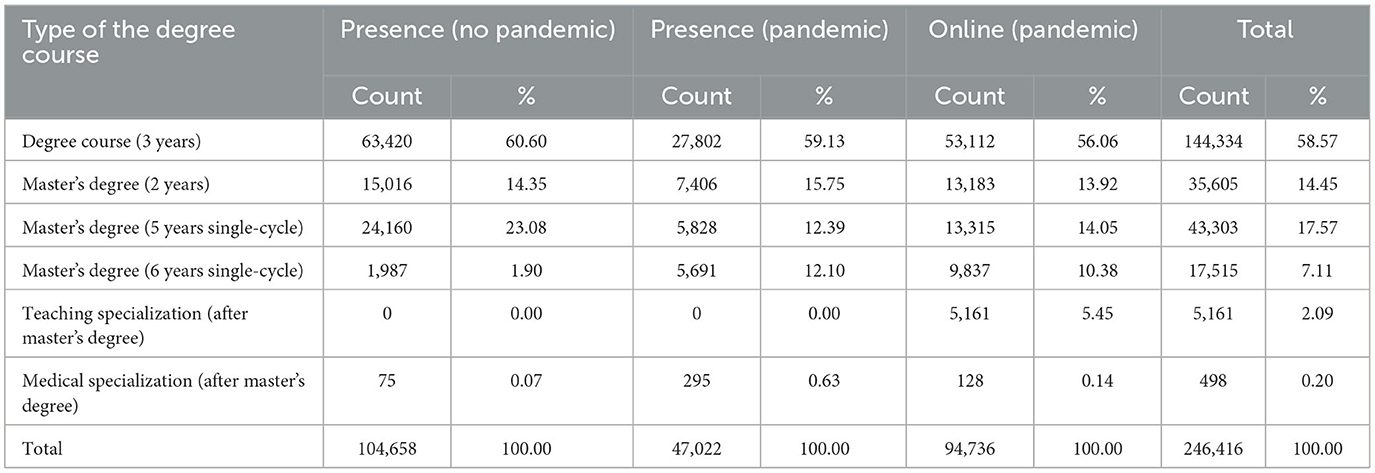

The data were extracted from the multifunction academic platform of the University of Messina. These data consisted of 246,416 assessments (exams) provided by 829 examiners. The evaluation involved 1,846 teaching courses. The data were collected over three academic years, from 2019 to 2021, and involved a total of 32,123 students [originating from 135 bachelor's/master's degrees and post-graduate specializations offered by the University of Messina (see Table 1 )].

Table 1 . Number of assessments and respective percentages per type of degree course before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

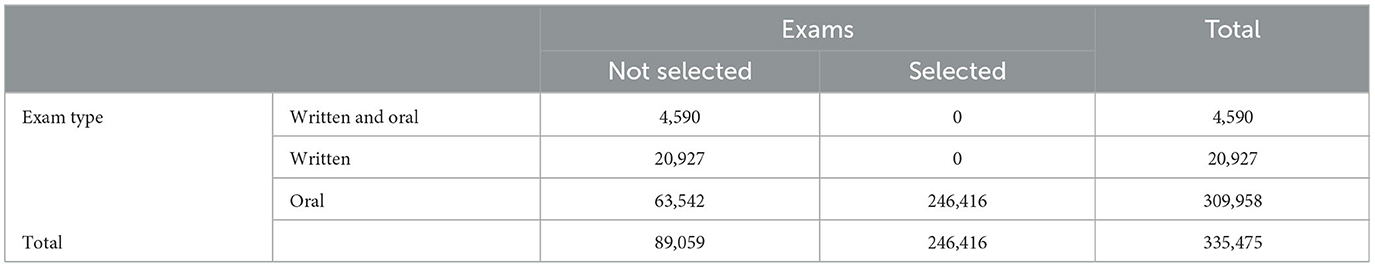

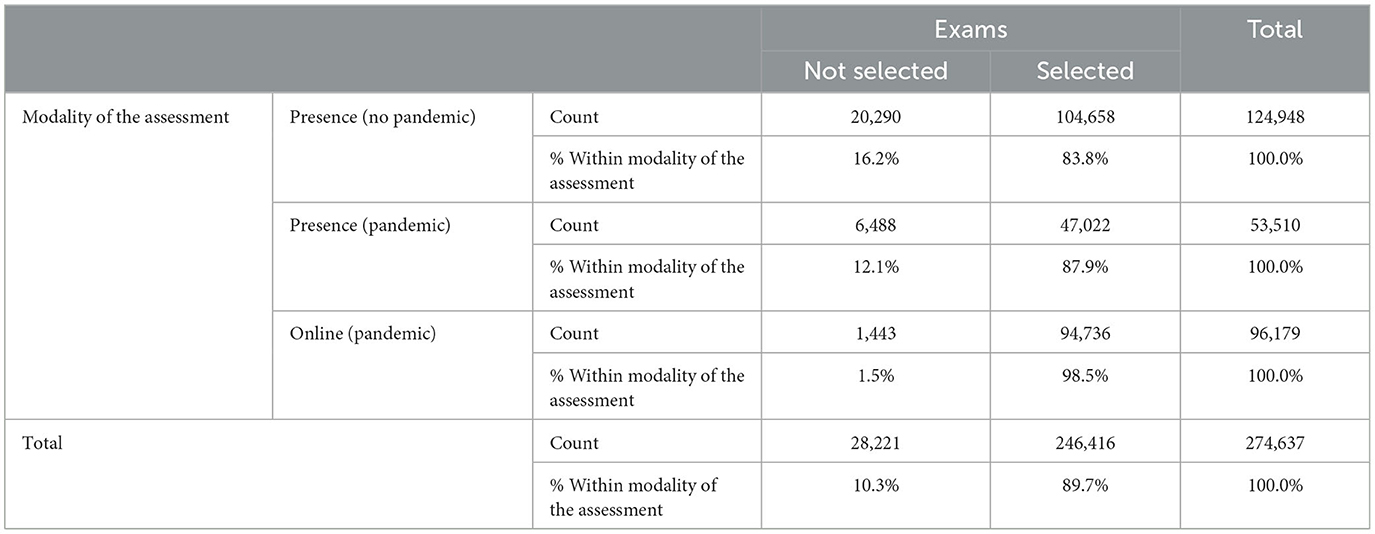

The pre-pandemic period refers to exams from January 2019 to February 2020. The pandemic period refers to exams from March 2020 to October 2021. We choose to include a relatively extended time window for the pandemic condition as two modalities of examination (i.e., in presence and online) were implemented in this period. In contrast, only one (in person) was available in the pre-pandemic condition. We excluded data referring to mixed mode (online/in person) assessments, as it was not possible to disentangle the two modalities. Refer to Tables 2 , 3 for more details.

Table 2 . Comparison between complete data and selection by exam type.

Table 3 . Comparison between complete data and selection by modality of the assessment.

The extracted data included the modality of the assessment session (online and in presence), the type of assessment (written and oral), and the respective outcome (passed or failed). Inclusion criteria for the final data analysis referred to only oral examinations. We excluded data referring to mixed mode (online/presence) assessments, as it was not possible to clearly disentangle the two modalities. We referred to rectoral decrees to determine when the exams were (or not) online or in the mixed mode. For privacy reasons, demographic data (e.g., age, sex, and country of origin) were not provided. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Protocol Number: COSPECS_08_2022). The ethics committee waived the requirement for consent as the study implied the analysis of already collected and anonymized data.

A typical oral exam session begins with verifying the student's identity. There is no standard way to conduct the exam. The assessor can start the session by asking the student to choose the topic from the general program of the course or by selecting the topic himself from those addressed in the course. The duration of the exam and the number of questions also vary depending on the assessor and the need to have a clear picture of the level of preparation of the student being examined. For data analysis we employed an approach to discern significant differences in pass rates between categories. Specifically, we utilized the prop.test() function in the R language, which conducts a hypothesis test to compare proportions. Internally, this function employs the chi-square test statistic for proportions. The version used for this analysis is R language ver. 4.2.

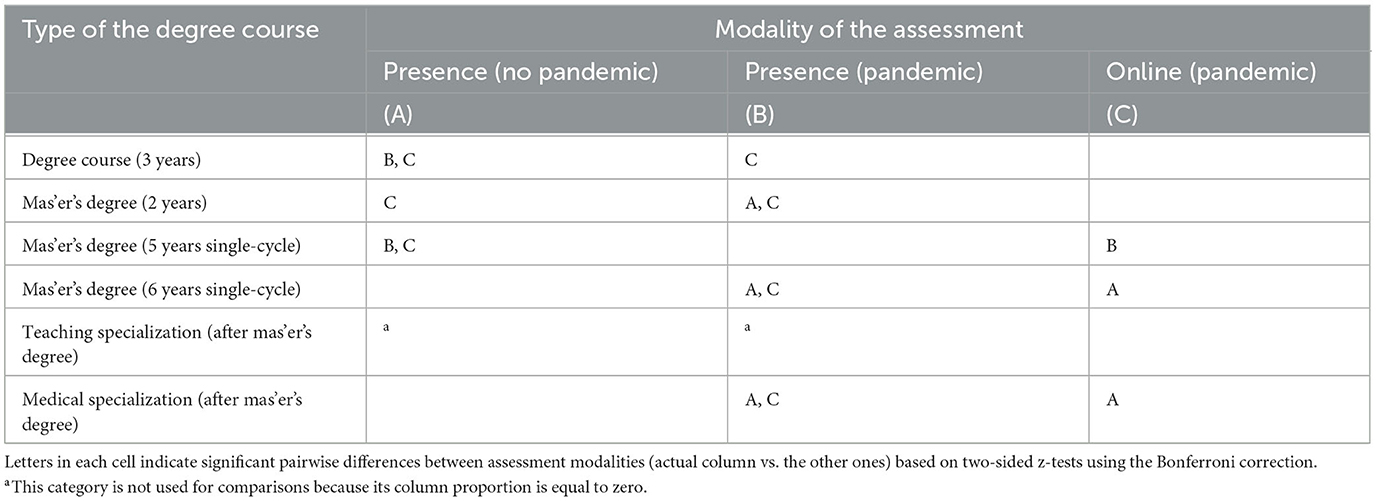

First, the overall number of assessments during the pandemic was higher ( N = 141.758) compared to the pre-pandemic period ( N = 104.658). However, when looking separately at each type of degree course ( Table 1 ), a reversed pattern of results (i.e., a lower number of assessments) is documented for the master's degree (5 years single cycle).

Table 4 provides the results of the statistical analysis when comparing the number of assessments before vs. during the pandemic for each type of degree course.

Table 4 . Statistical comparisons of the number of assessments as a function of assessment modalities (A = in presence before the pandemic; B = in presence during the pandemic; C = online during the pandemic) for each type of degree course.

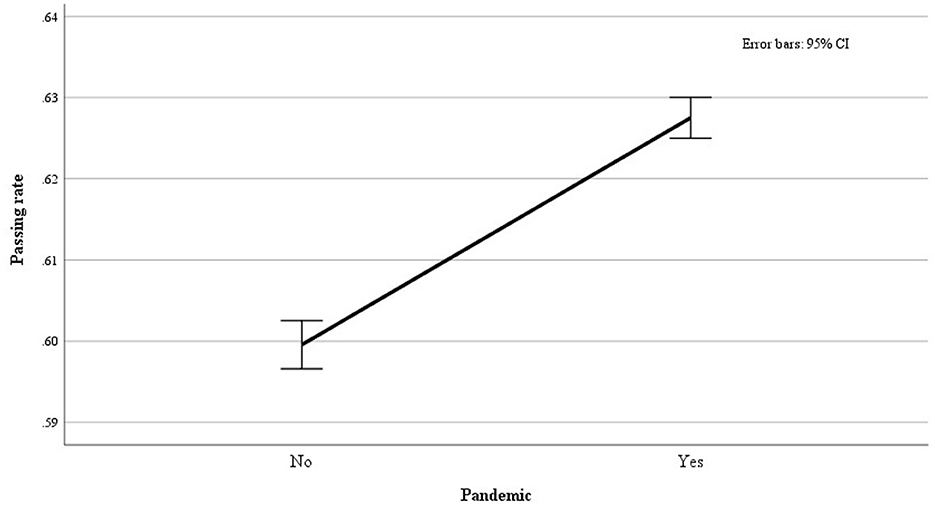

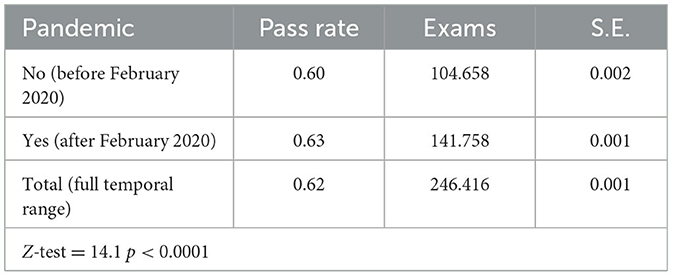

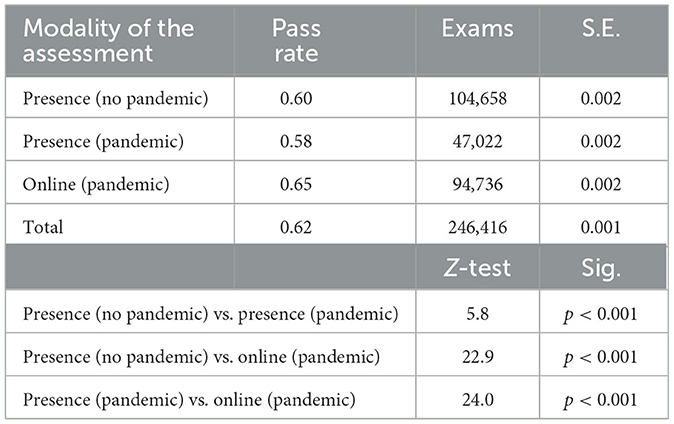

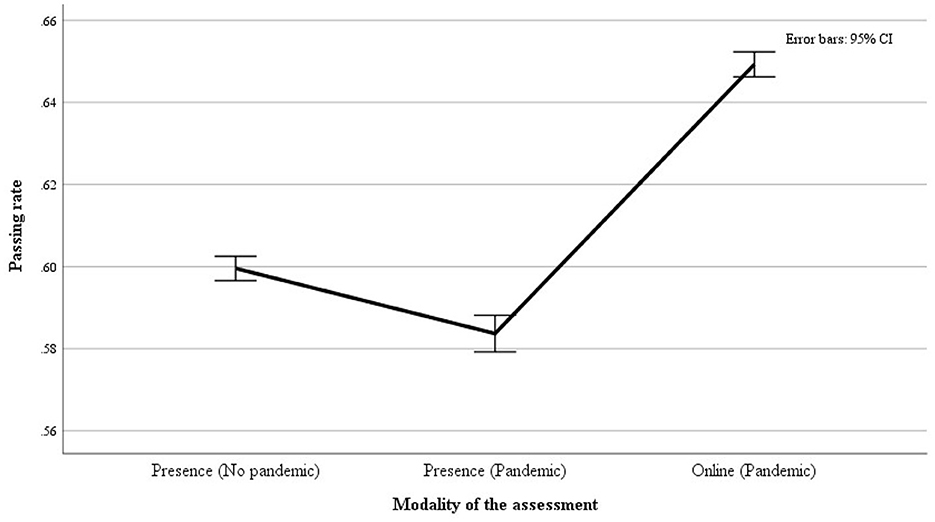

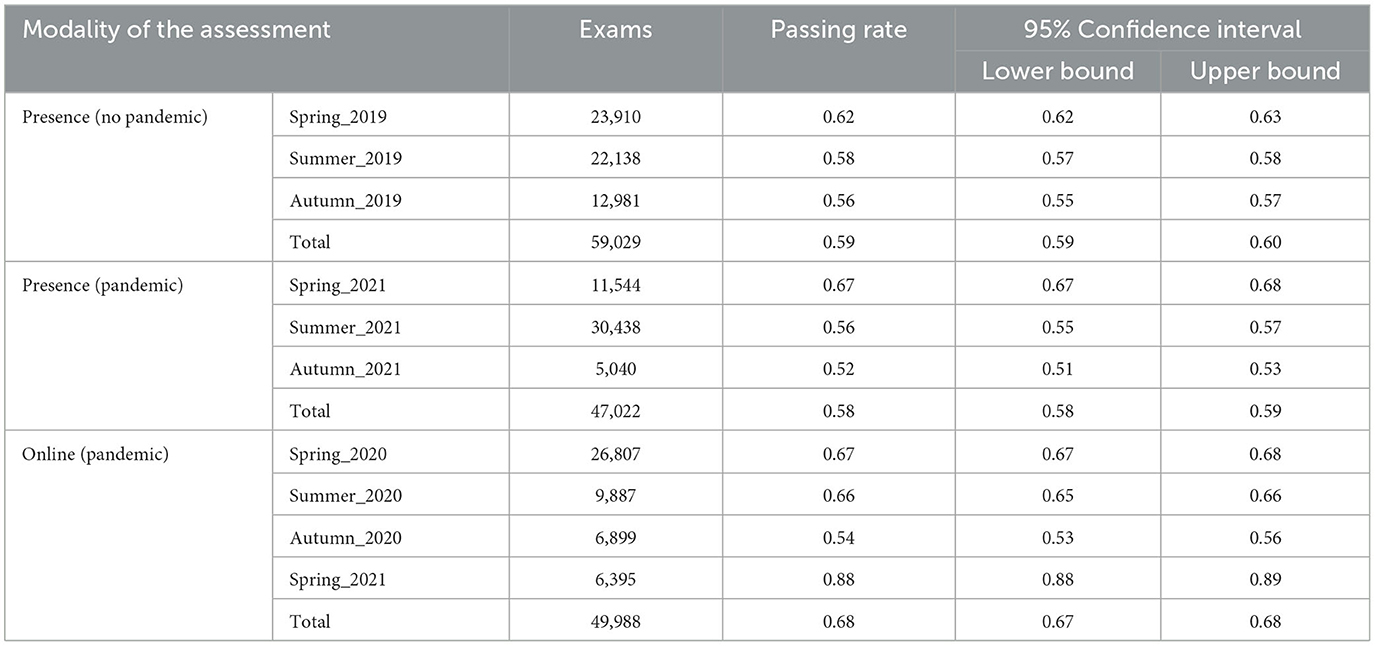

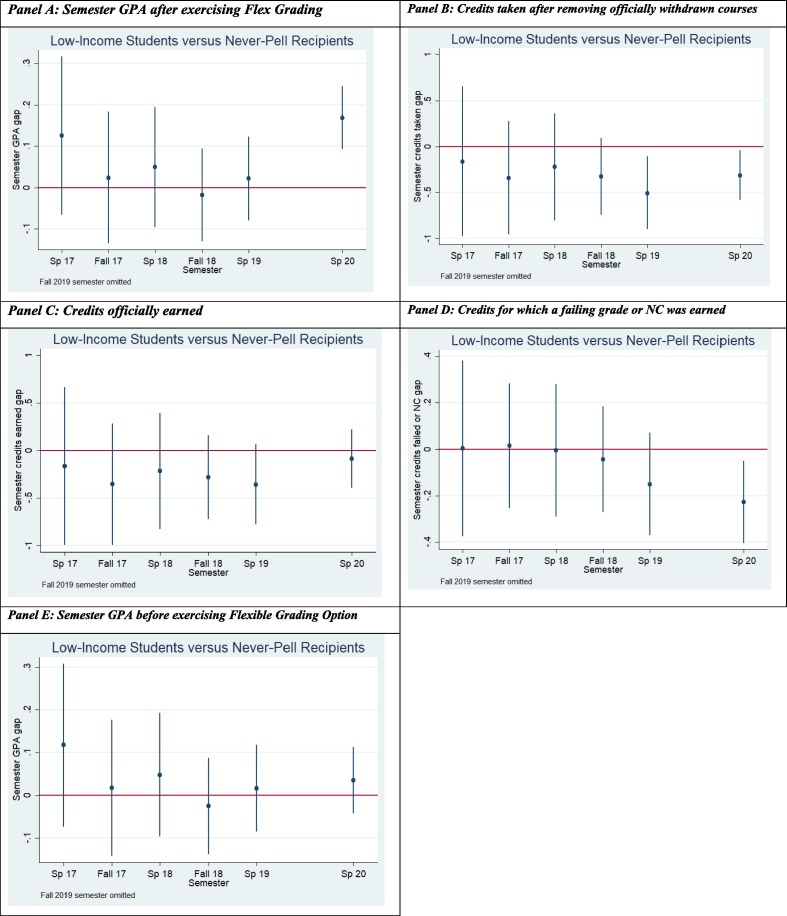

Considering the whole sample, the observed absolute number of passed exams was 151.702 out of 246.416, resulting in an overall pass rate of 0.62 (61.6%). Furthermore, we noted an overall higher chance of a favorable assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (0.63 vs. 0.60) ( Figure 1 and Table 5 ). However, a more mixed picture emerged when examining different assessment modalities. Specifically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the chance for a favorable assessment was higher in the “online” modality (0.65) but notably lower in the “in presence” modality (0.58), compared to the pre-pandemic “in presence” assessments (0.60). This indicates that the pandemic negatively influenced academic performance, specifically when the assessment was conducted in the standard (i.e., in presence) setting. See Table 6 and Figure 2 .

Figure 1 . The figure shows the pass rates in the COVID-19 pandemic (Yes) and before (No).

Table 5 . Pass rate by the assessment modality: number of examinations, standard error (S.E.), and Z- test for equality of proportions.

Table 6 . Pass rate by modality of the assessment: number of examinations, the respective standard error (S.E.), and Z- test.

Figure 2 . The figure shows the pass rate by modality of the assessment.

To account for potential season-related effects, we performed a further control analysis comparing passing rates between three consecutive years (2019, 2020, 2021) considering the same seasons for each of the 3 years. We excluded the winter season from the analysis because it encompassed both pre-pandemic and pandemic data, in accordance with the university's rectoral decree, which established the examination modality (online, face-to-face) for the entire institution. We examined the influence of seasons, and assessment modality on the likelihood/chance of a favorable assessment.

The results (two-sided Z -tests) confirm the pattern observed in the primary analysis, indicating a reduced likelihood of a favorable assessment in face-to-face settings during the pandemic (58%, p = 0.007), and an increased likelihood of a favorable evaluation online (during the pandemic, 68%, p < 0.001) compared to the pre-pandemic—face-to-face—setting condition (59%). See Table 7 for details on the different seasons.

Table 7 . Pass rate by modality of the assessment after controlling for the season effect.

In this archival study we examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic assessment outcomes, introducing several innovative elements compared to previous work in the field. Our approach combined direct empirical evidence about academic performance, a comprehensive archival analysis of large-scale data, and a comparison between face-to face and online assessments.

The first important finding is the significant difference of exam pass rates between face-to-face and online modalities. This has relevant practical implications for the landscape of academic assessment. In contrast to previous survey-based studies (e.g., Mahdy, 2020 ), our research, based on direct empirical evidence, demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected academic assessments, specifically in a face-to-face setting. This is evident through a decreased pass rate in the “in person” assessments during the pandemic compared to the period before the outbreak. Crucially, this trend persists even when accounting for seasonal effects, and might be caused by an adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health ( Salehinejad et al., 2020 ; Craparo et al., 2022 ; La Rosa et al., 2022 ; Vicario et al., 2023 ) and cognitive skills ( Fiorenzato et al., 2021 ), which could have deleterious effects on academic performance.

In principle, the lower pass rate in “face-to-face” assessments during the COVID-19 pandemic may also be influenced negatively by attendance in online classes provided during the pandemic, which could have affected learning quality. However, we observed a higher pass rate for online assessments during the pandemic (but see discussion below), and evidence from other studies suggests that online platforms and other modalities for remote practices, such as clinical interventions ( D'Oliveira et al., 2022 ; Prato et al., 2022 ) and remote learning ( Al-Maroof et al., 2021 ) allow for effective outcomes. Therefore, although we do not dismiss the possibility that online lectures may have negatively affected learning in some students, our data and previous research ( Al-Maroof et al., 2021 ) argue against attributing a causal role to this factor. On the other hand, “face-to-face” exams might have triggered heightened social stress, originating from prolonged isolation, which restricts social interactions. This, in turn, could have impacted students' cognitive performance and assessors' decision-making processes in the assessment (e.g., Starcke and Brand, 2012 ).

Other potential stressors, such as using facial masks, may have further reduced pass rates by interfering with student performance. The discomfort associated with face masking (e.g., Lazzarino et al., 2020 ; Tornero-Aguilera and Clemente-Suárez, 2021 ) has been shown to compromise cognitive performance and interfere with the occupational duties of workers (e.g., Shenal et al., 2012 ), and prolonged mask use can cause bilateral headaches ( Ong et al., 2020 ). Face masks may compromise the positive effects of relational continuity ( Wong et al., 2013 ). Additionally, facial masking reduces the recognition of emotions, potentially impacting social functioning ( Grundmann et al., 2021 ).

The second major finding in this study is the higher pass rate observed in the online assessment condition during the pandemic, suggesting a potential advantage for students tested in this modality. Also, this outcome remains consistent even after accounting for seasonal effects, indicating that the utilization of online platforms for assessment could increase the likelihood of passing exams during the pandemic. It is important to note, however, that no data on online assessments conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic are available, making it challenging to determine whether the increased pass rate is solely due to the use of the online platform or reflects an interaction between this assessment modality and the unique circumstances of the pandemic.

The more favorable outcome in the online session could potentially be attributed to a reduction in social distress experienced by students. This hypothesis is supported by the study of Stowell and Bennett (2010) , indicating that students who typically experience high levels of test anxiety in a classroom setting report reduced test anxiety when taking exams online. This might reflect an effective capacity to implement successful coping strategies crucial for an effective adaptation to unexpected circumstances associated with the ongoing pandemics (e.g., Zhao et al., 2022 ).

However, it is noteworthy that approximately one-third of students perceive e-exams as more stressful than in-person exams ( Elsalem et al., 2020 ).

Additionally, it is essential to acknowledge that previous research has emphasized an increased likelihood of cheating in (online) exams when lacking proctoring mechanisms (as in this case) (e.g., Harmor and Lambrinos, 2008 ; see also Chiang et al., 2022 , for a recent systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments). This underscores the potential risk of undeserved promotion associated with the use of telematic tools. However, it is important to recognize the relevance of these technologies in supporting the continuity of teaching and academic assessment during the challenging circumstances posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study significantly contributes to understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced academic assessment, shedding light on both challenges and opportunities associated with online platforms. We provide direct evidence of the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic performance when exams are conducted in person. Conversely, the observed higher pass rate in the online condition, compared to the in-person conditions both before and during the pandemic, suggests a potential drawback of this assessment modality. This includes an increased likelihood for students to consult notes and teaching material in the absence of a supervision system, and/or a higher inclination of assessors toward positive evaluations. However, it is important to note that this statement, which represents the main limitation of our work, remains unverified, as our study did not encompass the condition of online assessment before the COVID-19 pandemic for a comparative analysis with that during the pandemic. Moreover, other limitations pertain to the absence of control for additional variables that could have influenced the results, such as variations in learning styles, assessment methodologies, and socio-cultural factors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study extends the existing body of research (e.g., del Arco et al., 2021 ; Diotaiuti et al., 2021 ; Ramos-Pla et al., 2021 , 2022 ), underscoring the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic assessments and the use of virtual classes. For face-to-face examinations, it documents a lower probability of passing an exam during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic times. It also emphasizes disparities in pass rates between in-person and online assessments, indicating a higher likelihood of passing exams online compared to in-person. Potential factors that contribute to explaining these differences include the impact of the pandemic on students' mental wellbeing and/or the potential for academic dishonesty in online assessments. The discovery of a lower probability of passing exams during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic times suggests educational institutions need to formulate resilient contingency plans, crucial for mitigating disruptions in academic assessments resulting from unforeseen events such as pandemics.

The finding that the use of online platforms for assessment may increase the likelihood of passing exams holds practical implications for assessment strategies. It unveils, among other considerations, the potential risk of overestimating student‘s knowledge of the subject matter, which needs to be addressed.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be available by sending a formal request to COSPECS Department at ZGlwLmNvc3BlY3MmI3gwMDA0MDtwZWMudW5pbWUuaXQ= .

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Local Ethics Committee, Cospecs Department, University of Messina. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because we used archival data to conduct our study.

Author contributions

CV: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. PP: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MN: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The University of Messina covered the publication expenses for this article through the APC initiative. AA was supported by Universidad Católica Del Maule (CDPDS2022).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akin-Odanye, E. O., Kaninjing, E., Ndip, R. N., Warren, C. L., Asuzu, C. C., Lopez, I., et al. (2021). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on students at institutions of higher learning. Eur. J. Edu Stud. 8, 112–128 doi: 10.46827/ejes.v8i6.3770

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Aldossari, M., and Chaudhry, S. (2021). Women and burnout in the context of a pandemic. Gender Work Organ. 28, 826–834. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12567

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Al-Maroof, R. S., Alnazzawi, N., Akour, I. A., Ayoubi, K., Alhumaid, K., AlAhbabi, N. M., et al. (2021). The effectiveness of online platforms after the pandemic: Will face-to-face classes affect students' perception of their behavioural intention (BIU) to use online platforms? Informatics 8, 83. doi: 10.3390/informatics8040083

Andersen, S., Leon, G., Patel, D., Lee, C., and Simanton, E. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on academic performance and personal experience among first-year medical students. Med. Sci. Edu. 32, 389–397 doi: 10.1007/s40670-022-01537-6

Andrade, C. (2020). The limitations of online surveys. Indian J. Psychol. Med . 42, 575–576. doi: 10.1177/0253717620957496

Appleby, J. A., King, N., Saunders, K. E., Bast, A., Rivera, D., Byun, J., et al. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the experience and mental health of university students studying in Canada and the UK: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open . 24, e050187. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050187

Chiang, F.-K., Zhu, D., and Yu, W. (2022). A systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. J. Comp. Assesst Learn. 38, 907–928. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12656

Craparo, G., La Rosa, V. L., Commodari, E., Marino, G., Vezzoli, M., Faraci, P., et al. (2022). What is the role of psychological factors in long COVID syndrome? Latent class analysis in a sample of patients recovered from COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 494. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010494

del Arco, I., Flores, Ò., and Ramos-Pla, A. (2021). Structural model to determine the factors that affect the quality of emergency teaching, according to the perception of the student of the first university courses. Sustainability 13, 2945. doi: 10.3390/su13052945

Diotaiuti, P., Valente, G., Mancone, S., Corrado, S., Bellizzi, F., Falese, L., et al. (2023). Effects of cognitive appraisals on perceived self-efficacy and distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: an empirical analysis based on structural equation modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 5294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20075294

Diotaiuti, P., Valente, G., Mancone, S., Falese, L., Bellizzi, F., Anastasi, D., et al. (2021). Perception of risk, self-efficacy and social trust during the diffusion of COVID-19 in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 3427. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073427

D'Oliveira, A., De Souza, L. C., Langiano, E., Falese, L., Diotaiuti, P., Vilarino, G. T., et al. (2022). Home physical exercise protocol for older adults, applied remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic: protocol for randomized and controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 13, 828495. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828495

Elsalem, L., Al-Azzam, N., um'ah, A. A., Obeidat, N., Sindiani, A. M., and Kheirallah, K.A. (2020). Stress and behavioral changes with remote E-exams during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study among undergraduates of medical sciences. Ann. Med. Surgery . 60, 271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.10.058

Estrada Guillén, M., Monferrer Tirado, D., and Rodríguez Sánchez, A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on university students and competences in education for sustainable development: emotional intelligence, resilience and engagement. J. Clean Prod. 380:135057. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135057

Fardoun, H., González-González, C., Collazos, C. A., and Yousef, M. (2020). Exploratory study in iberomaerica on the teaching-learning process and assessment proposal in the Pandemic. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 21, 1–9. doi: 10.14201/eks.23537

Fiorenzato, E., Zabberoni, S., Costa, A., and Cona, G. (2021). Cognitive and mental health changes and their vulnerability factors related to COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. PLoS ONE 16, e0246204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246204

Gewalt, S. C., Berger, S., Krisam, R., and Breuer, M. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university studets' physical health, mental health and learning, a cross-sectional study including 917 students from eight universities in Germany. PLoS ONE. 17, e0273928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273928

Giusti, L., Mammarella, S., Salza, A., Del Vecchio, S., Ussorio, D., Casacchia, M., et al. (2021). Predictors of academic performance during the Covid-19 outbreak: impact of distance education on mental health, social cognition and memory abilities in an Italian university student sample. BMC Psychol. 9, 142. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00649-9

Gonzalez, T., de la Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., et al. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students' performance in higher education. PLoS ONE 15, e0239490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239490

Grundmann, F., Epstude, K., and Scheibe, S. (2021). Face masks reduce emotion-recognition accuracy and perceived closeness. PLoS ONE 16, e0249792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249792

Hadwin, A. F., Sukhawathanakul, P., Rostampour, R., and Bahena-Olivares, L. M. (2022). Do self-regulated learning practices and intervention mitigate the impact of academic challenges and COVID-19 distress on academic performance during online learning? Front. Psychol. 13, 813529. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813529

Harmor, O. R., and Lambrinos, J. (2008). Are online exams an invitation to cheat? J. Econ. Edu. 39, 116–125. doi: 10.3200/JECE.39.2.116-125

Hays, R. D., Liu, H., and Kapteyn, A. (2015). Use of Internet panels to conduct surveys. Behav. Res. Methods 47, 685–690 doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0617-9

Keržič, D., Alex, J. K., Pamela Balbontín Alvarado, R., Bezerra, D. D. S., Cheraghi, M., Dobrowolska, B., et al. (2021). Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the e-learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence across ten countries. PLoS ONE . 16, e0258807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258807

La Rosa, V. L., Gori, A., Faraci, P., Vicario, C. M., and Craparo, G. (2022). Traumatic distress, alexithymia, dissociation, and risk of addiction during the first wave of COVID-19 in Italy: results from a cross-sectional online survey on a non-clinical adult sample. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 20, 3128–3144. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00569-0

Lazzarino, A. I., Steptoe, A., Hamer, M., and Michie, S. (2020). COVID-19: important potential side effects of wearing face masks that we should bear in mind. BMJ . 369, m2003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2003

Mahdy, M. A. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the academic performance of veterinary medical students. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 594261. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.594261

Ong, J. J. Y., Bharatendu, C., Goh, Y., Tang, J. Z. Y., Sooi, K. W. X., Tan, Y. L., et al. (2020). Headaches associated with personal protective equipment - a cross-sectional study among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Headache 60, 864–877. doi: 10.1111/head.13811

Onyema, E. M., Eucheria, N. C., Obafemi, F. A., Sen, S., Atonye, F. G., Sharma, A., et al. (2020). Impact of coronavirus pandemic on education. J. Educ. Pract. 11, 108–121. doi: 10.7176/JEP/11-13-12

Prato, A., Maugeri, N., Chiarotti, F., Morcaldi, L., Vicario, C. M., Barone, R., et al. (2022). Randomized controlled trial comparing videoconference vs. face-to-face delivery of behavior therapy for youths with tourette syndrome in the time of COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 13, 862422. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.862422

Radu, M. C., Schnakovszky, C., Herghelegiu, E., Ciubotariu, V. A., and Cristea, I. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of educational process: a student survey. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health. 17, 7770. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217770

Ramos-Pla, A., del Arco, I., and Flores Alarcia, Ò. (2021). University professor training in times of COVID-19: analysis of training programs and perception of impact on teaching practices. Educ. Sci. 11, 684. doi: 10.3390/educsci11110684

Ramos-Pla, A., Reese, L., Arce, C., Balladares, J., and Fiallos, B. (2022). Teaching online: lessons learned about methodological strategies in postgraduate studies. Educ. Sci. 12, 688. doi: 10.3390/educsci12100688

Ramos-Pla, A., Requena, B. S., del Arco, I., Díaz, V. M., and Flores-Alarcia, Ò. (2023). Training, personal and environmental barriers of online education. Educar 59. 457–471. doi: 10.5565/rev/educar.1743

Rania, N., Pinna, L., and Coppola, I. (2022). Living with COVID-19: emotions and health during the pandemic. Health Psychol. Rep. 10, 212–226. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2022.115795

Rashid, S., and Yadav, S. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on higher education and research. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 14, 340–343. doi: 10.1177/0973703020946700

Salehinejad, M. A., Majidinezhad, M., Ghanavati, E., Kouestanian, S., Vicario, C. M., Nitsche, M. A., et al. (2020). Negative impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep quantitative parameters, quality, and circadian alignment: implications for health and psychological well-being. EXCLI J. 19, 1297–1308. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.09.20149138

Shenal, B. V., Radonovich, L. Jr, Cheng, J., Hodgson, M., and Bender, B. S. (2012). Discomfort and exertion associated with prolonged wear of respiratory protection in a health care setting. J. Occup. Environ. Hygiene 9, 59–64. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.635133

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., and Sasangohar, F. J. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students' mental health in the United States: interview survey study. Med. Internet Res. 22, e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279

Starcke, K., and Brand, M. (2012). Decision making under stress: a selective review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1228–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.003

Stowell, J. R., and Bennett, D. (2010). Effects of online testing on student exam performance and test anxiety. J. Edu. Comp. Res. 42, 161–171. doi: 10.2190/EC.42.2.b

Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., and Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2021). Cognitive and psychophysiological impact of surgical mask use during university lessons. Physiol. Behav. 234, 113342. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113342

Vicario, C. M., Makris, S., Culicetto, L., Lucifora, C., Falzone, A., Martino, G., et al. (2023). Evidence of altered fear extinction learning in individuals with high vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Neuropsychiatry . 20, 364–369. doi: 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20230417

Wilke, J., Hollander, K., Mohr, L., Edouard, P., Fossati, C., González-Gross, M., et al. (2021). Drastic reductions in mental well-being observed globally during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the ASAP survey. Front. Med. 8, 578959. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.578959

Wong, C. K., Yip, B. H., Mercer, S., Griffiths, S., Kung, K., Wong, M. C., et al. (2013). Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 14, 200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-200

Zhao, Y., Ding, Y., Chekired, H., and Wu, Y. (2022). Student adaptation to college and coping in relation to adjustment during COVID-19: a machine learning approach. PLoS ONE . 17, e0279711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279711

Keywords: academic assessment, COVID-19 pandemic, online assessment, face-to-face assessment, archival study, archive statistical analysis

Citation: Vicario CM, Mucciardi M, Perconti P, Lucifora C, Nitsche MA and Avenanti A (2024) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic performance: a comparative analysis of face-to face and online assessment. Front. Psychol. 14:1299136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1299136

Received: 22 September 2023; Accepted: 18 December 2023; Published: 09 January 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Vicario, Mucciardi, Perconti, Lucifora, Nitsche and Avenanti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carmelo Mario Vicario, Y3ZpY2FyaW8mI3gwMDA0MDt1bmltZS5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Lessons From Early COVID-19: Associations With Undergraduate Students’ Academic Performance, Social Life, and Mental Health in the United States

Joseph p nano, mina h ghaly.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Olaf von dem Knesebeck , University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany

Reviewed by: Jesus Alejandro Aldana Lopez , Instituto Jalisciense de Salud Mental, Mexico

*Correspondence: Joseph P. Nano, [email protected] ; Mina H. Ghaly, [email protected]

These authors share first authorship

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health”

Received 2022 Jan 28; Accepted 2022 Nov 28; Collection date 2022.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Objectives: This study aims to explore the influence of COVID-19 on undergraduate students’ academic performance, social life, and mental health during the pandemic’s early stage, and evaluate potential correlates of stress, anxiety, and depression in relation to COVID-19.

Methods: Participant data was collected as part of a survey that consisted of demographic questions, a DASS-21 questionnaire, and an open-ended question. The final sample consisted of 1077 full-time students in the United States.

Results: 19%, 20%, and 28% of participants met the cutoff for “severe” and “extremely severe” levels of stress, anxiety, and depression according to DASS-21. During COVID-19, a significant increase in hours of sleep, and decrease in hours spent on extracurriculars and studying were observed. While talking to family was significantly associated with stress, anxiety, and depression, engaging in hobbies was only associated with depression.

Conclusion: With the continued spread of COVID-19, it is critical for universities to adapt to the mental health needs of their students. Future institutional advancements should create treatment programs to ensure better academic and social outcomes.

Keywords: anxiety, mental health, COVID-19, depression, stress, DASS-21, undergraduate students

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the rapidly spreading coronavirus outbreak a pandemic [ 1 ]. The pandemic has since reshaped almost every facet of modern society. Many schools and universities across the United States closed from March 2020 through the end of the Spring 2020 semester. Consequently, students living in university dormitories were required to return to tumultuous living conditions that likely detracted from learning. Educators were asked to revise, and in some cases completely revamp course standards, expectations, and assessments, all within a matter of weeks.

Despite limited evidence regarding the implications of transitioning to online learning in the context of COVID-19, previous studies have shown that the transition to postsecondary education is itself a source of anxiety [ 2 ], stress [ 3 ], and depression [ 2 , 4 ]. This transition can bring about feelings of worthlessness, appetite disturbances, and issues with concentration, all of which adversely affect students’ capability to perform well in demanding environments [ 5 ]. Moreover, during the undergraduate years, students are not only immersed in higher education but are also transitioning into other critical social roles [ 6 ]. Young adults in this age range, therefore, are forced to deal with identity exploration and adjustment to university life.

Academics are exceptionally fundamental to the life and health of undergraduate students. The amount of time spent studying as well as concerns about examinations have been shown to lead to heightened immune and stress responses [ 7 ]. Therefore, coping mechanisms and social support to reduce stress are crucial, as effective coping strategies can potentially ameliorate stress reactivity [ 8 ]. In particular, understanding how the learning experience was for undergraduate students is important as online learning will likely be the primary method of instruction during future university closures. Some research has been done to assess early pandemic-related responses associated with undergraduate students’ academic work [ 9 , 10 ] and mental health [ 11 ] in the United States.

Coinciding with the ever-demanding academic burden, mental health among undergraduate students represents an important and growing public health concern [ 12 ]. It was found that 12%–18% of college students suffer from a diagnosable mental illness [ 13 ]. A mental health crisis may take its toll years after the course of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 14 ]. Thus, it is important to investigate the potential factors that have adversely affected students during the pandemic.

Literature to-date is limited on commentary with regards to the effects of online learning on studying quality among undergraduates during the pandemic. The abrupt transition to online learning exploited time better spent in clinical training and internet subscription costs impeded access to effective learning for students studying at home, as did tending to family [ 15 ]. A poor internet connection was found to be a leading barrier to online learning [ 16 ].

Undergraduates are one of the most sleep-deprived age groups in the United States [ 17 ]. Studies that have investigated sleep reported significantly worsened insomnia among students during the pandemic [ 18 , 19 ]. Specifically, a large cross-sectional study found a marked incidence of insomnia among college-aged students during the lockdown period [ 20 ]. Deteriorating sleep quality correlated with depressive symptoms [ 21 ].

While previous studies have commented on particular dimensions of the pandemic relating to issues of depression and anxiety [ 22 ], there remains a pressing concern to determine precisely which aspects of students’ daily life had been affected. Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyze specific correlates of stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students as they relate to the most intimate issues of the college student’s demanding lifestyle. In particular, we aimed to analyze data from a large sample of students using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) to approximate emotional valence. Further questions offered to students in a survey were meant to gauge whether changes in hours spent on extracurricular activities, studying, and sleep before and during the pandemic were related to observed DASS-21 results. This study also aimed to provide a better understanding about COVID-19’s influence in the context of full-time undergraduate students’ academic performance, social life, and mental health in the United States.

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students at a private university, public university, or community college in the United States. To be included, participants had to be at least 18 years old and enrolled as full-time students as part of class years 2020, 2021, 2022, or 2023. Between April and June 2020, participants were recruited through two channels. First, an email was sent to undergraduate students at Boston College. Second, participants were recruited online via Reddit, a social news platform and online forum.

An invitation to participate in the study was posted on over 20 university-related and survey recruitment subreddits (a subreddit is an online community with user-created threads dedicated to a specific topic). One such subreddit utilized for recruitment in this study was r/SampleSize, a community of over 40,000 users assembled for the express purpose of survey recruitment and participation [ 23 ]. Subreddits such as these have been shown to be a good source of diverse and viable participants [ 23 ] and are useful for inexpensive participant recruitment and reliable data collection [ 24 , 25 ]. For the purpose of the current study, face-to-face interviews during this time had to be avoided because of the US lockdown and ongoing public health crisis. The study received 1,734 completed responses. After excluding students younger than 18 ( n = 34), part-time students ( n = 135), and students with incomplete responses ( n = 488) from our analyses, our final sample size was 1,077.

DASS (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale): The online survey included the 21-item DASS-21 scale on mood and stress [ 26 ]. Based on the scores, participants were classified into “normal” (a score of 0–9 for depression, 0–7 for anxiety, and 0–14 for stress), “mild” (10–13, 8–9, 15–18), “moderate” (14–20, 10–14, 19–25), “severe” (21–27, 15–19, 26–33), and “extremely severe” (28+, 20+, 34+) categories. The purpose of these questions was to assess the severity of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies have verified the validity of the DASS-21 scale as a routinely-used clinical and non-clinical self-report scale [ 27 , 28 ]. One sample statement that participants were to score for depression was “I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything”; one sample statement for anxiety was “I worry about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”; and one sample statement for stress was “I tended to over-react to situations”. Participants were given the option to choose between “once a week or less” (score = 0), “2–3 times a week” (= 1), “4–6 times a week” (= 2) and “7 times a week or more” (= 3). The corresponding sum of scores was used to assess the severity of depression, anxiety, and stress. Cronbach’s α for the items in this test was 0.934, indicating excellent internal consistency in the questionnaire.

COVID-19 Evaluation: The first portion of the survey consisted of a series of questions meant to measure how COVID-19 may have affected students’ social life and mental health. Students were asked about hours of studying per day (“1–2 h,” “3–5 h,” “5–8 h,” and “8+ h”), hours spent on extracurricular activities per week (participants typed in number of hours), and hours of sleep received per night (“4 h or less,” “5–7 h,” “7–8 h,” and “8+ h”) before the pandemic (e.g., “ How many hours of sleep did you get per night (BEFORE the COVID-19 pandemic)? ”) and during the pandemic (e.g., “ How many hours of sleep do you [currently] get per night? ”).

Coping Strategies: Participants were asked to select up to three ways they managed their stress. Seven response categories were given: “talk to friends,” “talk to family members,” “home workout/indoor sports,” “meditate,” “do favorite hobbies,” “walk outside,” and “other”. When participants chose “other”, they were asked to specify. Participants were provided with an open-ended question at the end of the survey to further elaborate on experiences that were not captured by previous questions.

Before taking the survey, all participants provided informed consent. Participants were made aware of all risks and benefits associated with the survey, confidentiality, and right to withdraw their voluntary participation at any time. The survey, which took 10 min to complete, consisted of four components: social demographics, school adjustments, DASS-21 questions, and an optional open-ended question. As an incentive for participation, participants were entered into a raffle for a chance to win a $10 Amazon gift card (15 participants were awarded a gift card). The survey was accessible online for 9 weeks (from April to June 2020). The procedure was approved by the university’s institutional review board in April 2020, ensuring the protection of human subjects in this research in compliance with US federal law.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R-Studio statistical software (version 1.3.959, 2009–2020 R-Studio, PBC). In the first phase of analysis, descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographics of the sample and the distribution of the three mental health outcomes among students. Next, t-tests were used to test whether moving to remote learning had an effect on stress, anxiety, and depression. Paired t-tests were used to determine differences in the hours of sleep, study, and extracurricular activities before and during the pandemic. Bivariate regression analysis was used to determine whether participants’ responses to moving classes to remote learning were associated with stress, anxiety, and depression. Regression analysis tested whether changes in the hours of sleep and study during COVID-19 were associated with stress, anxiety, and depression. Lastly, a multivariate OLS system was used to determine whether gender, having a family member who tested positive for COVID-19, number of times participants left their homes, school performance after moving to remote learning, and changes in the hours of sleep and studying were associated with stress, anxiety, and depression.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Most participants were students at public universities (70.5%), followed by those from private universities (28.5%) or community colleges (0.7%). 0.3% of participants preferred not to answer this question. Participants were categorized as students in the class of 2020 (16.6%), 2021 (26.1%), 2022 (29.1%), and 2023 (24.4%), respectively. 3.8% of participants preferred not to answer this question ( Table 1 ). Female participants accounted for 51.4% of the sample. Slightly more than half of the participants were Caucasian (52.8%), one fourth were Asian/Pacific Islander (24.7%), about one tenth were Hispanic/Latinx (8.9%), and about 4% were African American (3.7%). 0.4% of participants self-identified as Native American. While the majority of participants were US students (94.3%), some participants were international students (4.9%) and a few participants preferred not to answer (0.8%).

Demographic characteristics of participants (United States. 2020).

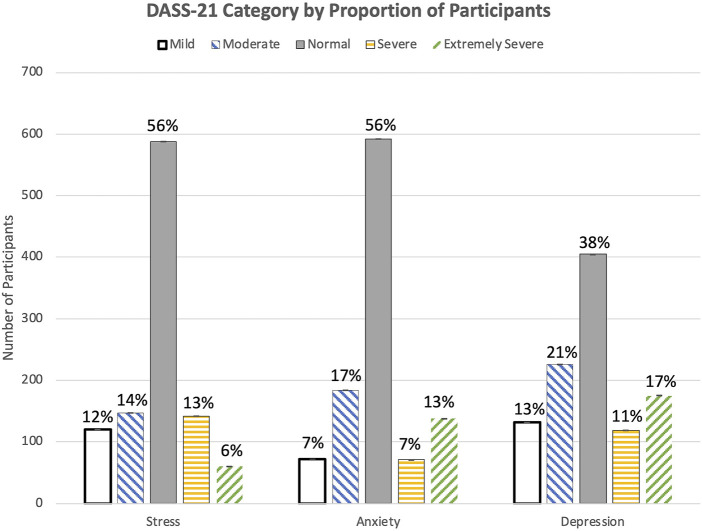

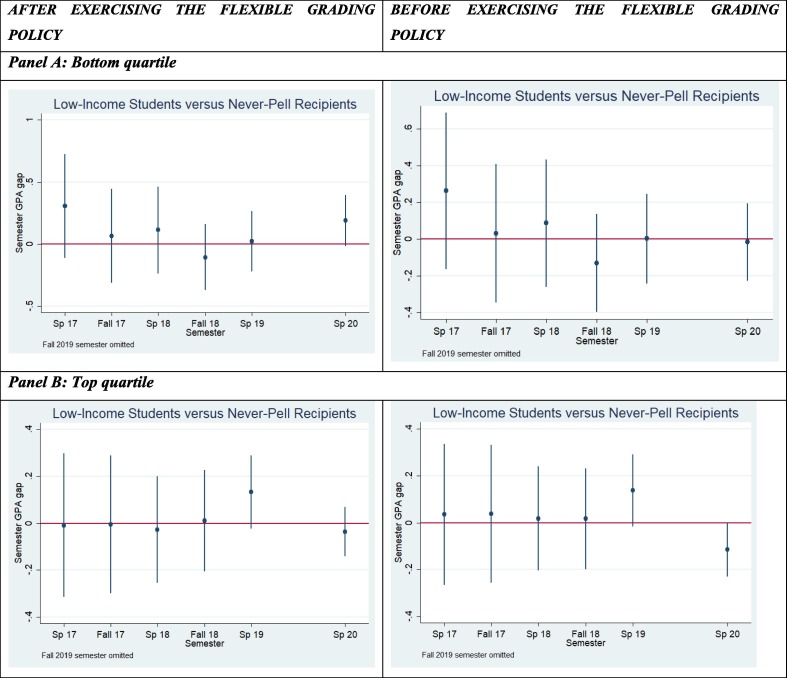

Using DASS-21 scores, 19%, 20%, and 28% of participants were categorized as having “severe” or “extremely severe” levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, respectively (% “severe” + % “extremely severe”) ( Figure 1 ) ( Table 2 ). These results indicate an increase of “severe” and “extremely severe” levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in comparison to a sample baseline, non-pandemic DASS-21 scores, with levels of stress, anxiety, and depression at 11%, 15%, and 11%, respectively [ 29 ].

Proportion of participants whose answers on the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 indicated a normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe level of stress, anxiety, and depression (United States. 2020).

Stress, anxiety, and depression characteristics of participants (United States. 2020).

Bivariate Relationship Between Academic Performance, Social Life, and Mental Health

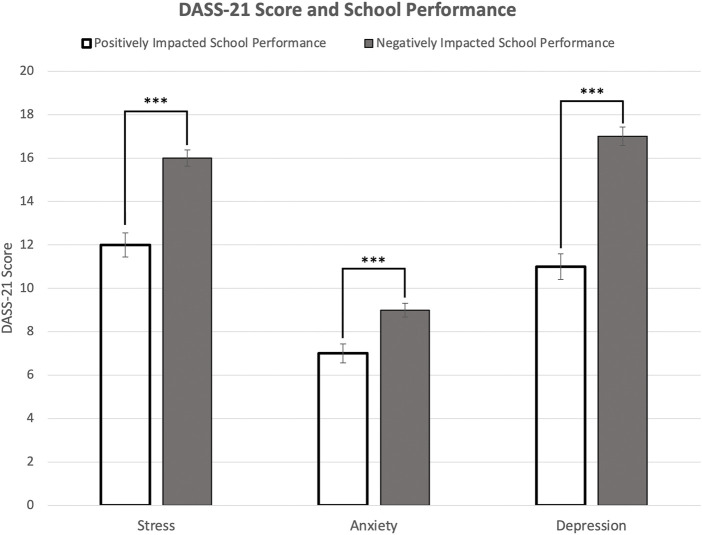

COVID-19 disrupted traditional classroom instruction and led to remote learning, as 69.3% of participants claimed that moving to remote learning had a negative impact on their school performance, while 30.7% of participants noted a positive impact of remote learning on school performance. Moreover, in terms of the association between school performance and mental health, a t-test showed that participants who claimed that remote learning had a negative impact on their school performance had significantly higher scores in stress ( Figure 2 , p < 0.001), anxiety ( Figure 2 , p < 0.001), and depression ( Figure 2 , p < 0.001), compared to peers who reported the opposite. A bivariate regression analysis further confirmed that students’ opinions about remote learning were significantly associated with stress ( p < 0.001), anxiety ( p < 0.001), and depression ( p < 0.001). Participants were also asked about changes in hours spent on extracurricular activities, studying, and sleeping before and during COVID-19 comparatively. A paired two-sample t-test showed a significant increase in the hours of sleep (before COVID-19: 6.7 h; during COVID-19: 7.7 h, p < 0.001), a significant decrease in hours spent on extracurricular activities (before COVID-19: 9.4 h; during COVID-19: 6.2 h, p < 0.001), and a significant decrease in hours spent studying (before COVID-19: 4.2 h; during COVID-19: 3.6 h, p < 0.001).

Association between stress, anxiety, and depression scores (mean Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 score) and self-reported impact of COVID-19 on school performance (United States. 2020). Note: Error bars represent standard errors. Significance levels of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 scores: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Regression analysis was implemented to find correlates of stress, anxiety, and depression. For survey questions addressed in regard to pre-pandemic conditions, regression analysis showed that hours of sleep was associated with stress ( p < 0.001), anxiety ( p < 0.001), and depression ( p < 0.001), but hours of studying was not associated with stress ( p = 0.33), anxiety ( p = 0.213), and depression ( p = 0.056). However, during COVID-19, regression analysis showed that neither hours of studying nor hours of sleep were associated with stress ( p = 0.429 and p = 0.678), anxiety ( p = 0.283 and p = 0.506), and depression ( p = 0.0517 and p = 0.665).

Multivariate OLS Regression Models

Turning to multivariate OLS regression models, several factors were found to have significant associations with stress and anxiety. Being a male participant ( p < 0.001), having a family member who tested positive ( p < 0.001), leaving home three times a week ( p < 0.05), believing that school performance was affected negatively by moving to remote learning ( Figure 2 , p < 0.001), and hours of sleep during COVID-19 (“5–6 h” p < 0.05, “7–8 h” p < 0.001, “8+ h” p < 0.001) were significant correlates of stress ( Table 3 ). As for depression, being a male participant ( p < 0.01), leaving home once a week ( p < 0.05), believing that school performance was affected negatively by moving to remote learning ( p < 0.001), hours spent studying (“3–5 h” p < 0.001, “5–8 h” p < 0.05), and hours of sleep during COVID-19 (“5–6 h” p < 0.01, “7–8 h” p < 0.001, “8+ h” p < 0.001) were significant correlates. For stress management, talking to a family member was significantly associated with stress ( p < 0.05), anxiety ( p < 0.05), and depression ( p < 0.05). Engaging in favorite hobbies was only correlated with depression ( p < 0.05).

Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares Models for variables indicative of stress, anxiety, and depression (United States. 2020).

Note : * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Sex Differences

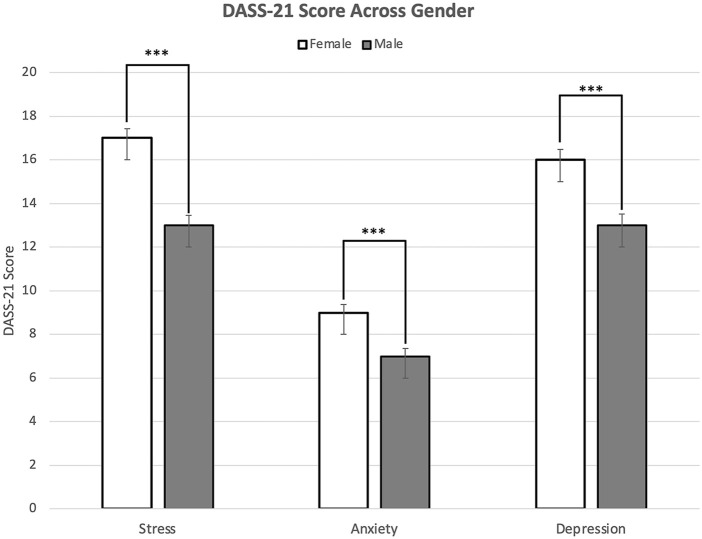

Female participants showed a larger percentage of severe and extremely severe levels of stress (severe; 16% and extremely severe; 7%), anxiety (8%; 15%), and depression (12%; 18%) in comparison to male participants’ stress (severe; 11% and extremely severe 3%), anxiety (5%; 10%), and depression (11%; 14%) levels ( Figure 3 ). Chi-squared analysis showed being female was associated with severe and extremely severe levels of stress (x-squared = 30.497, df = 4, p < 0.001), anxiety (x-squared = 19.501, df = 4, p < 0.001), and depression (x-squared = 17.59, df = 4, p < 0.01). Two-sample t-test showed that female participants have a higher score in stress ( p < 0.001), anxiety ( p < 0.001), and depression ( p < 0.001) in comparison to male participants. Regression analysis showed that gender is associated with stress ( p < 0.001), anxiety ( p < 0.001), and depression ( p < 0.001).

Mean Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 scores of stress, anxiety, and depression among males and females (United States. 2020). Note: Error bars represent standard errors. Significance levels of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 scores: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Stress Management

Recall that the survey asked participants to choose up to three ways they managed their stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost half (47.9%) of participants reported that they talked to family members, 76% of participants engaged in their favorite hobbies, and 32.2% of participants walked outside as one of their three choices. Although the vast majority of the open-ended responses included some sentiment of stress, many individuals did have positive experiences to share. Some participants noted that conversing with significant others, in addition to immediate family, was cathartic (“I’ve been [...]reach [ing] out to my boyfriend, at the very least. These things, along with the positive experience of being around a happy family and the safety of our own home, has positively contributed to my mental wellbeing.”). In a simpler sense, some have made the most of their time while at home, with one participant noting that they were “Just staying inside and trying to learn new things.”

Stress During COVID-19

In the open-ended question, one participant from the class of 2021 said the following of their experience during lockdown: “I have been feeling quite depressed. I feel like I have no control over my life ... I cannot plan for the future and my extracurriculars that were going to help me prepare for grad schools have been affected.” Another participant from the class of 2021 said, “Anxious and overwhelmed … I feel like I have less access to academic advising because … professors have not answered my emails. It’s been difficult to focus at home because my parents [are] working over the phone ….”

Many individuals expressed a lack of motivation to perform well on academic tasks noting severe procrastination, loss of direction, and overall dissatisfaction with the progression of the semester. One participant said, “I feel … grateful that I am healthy. However, I also have struggled to find any motivation to do my work or be active. Usually I can get things done because I look forward to having fun or relaxing on weekends, but now it is harder to get things done when it feels like that is all I am doing with nothing fun to look forward to.” Other participants found it challenging to engage with online classes. For example, one participant said, “Online learning is difficult because I feel zero engagement.”

One participant said that they felt suffocated. They said, “I want to leave the house, see new people, go to stores, but I only leave my house about 1–2 times a week.” In addition, leaving home a few times a week may have given students the opportunity to distance themselves from their families and home environment. One participant said, “My parents and I argue, and I feel like my mental health issues are having a negative effect on my family.” Another participant talked about the challenge of staying at home with family, saying, “Being at home with my family has taken a toll on my mental health. [We] do not have a great relationship, and being stuck at home has exacerbated our problems … ” One participant claimed that living temporarily away from family made them “feel great.”

This study looked for correlates of stress, anxiety, and depression during COVID-19. Those who reported that school performance was affected negatively by moving to remote learning exhibited significantly heightened levels of stress, as predicted by previous findings [ 30 , 31 ]. The classroom environment has several advantages over online learning. Teachers, for instance, are able to receive immediate feedback on students’ understanding of key concepts [ 32 ]. Furthermore, with remote learning comes some disadvantages; problematic internet use, longer screen time, isolation, and academic pressure are all associated with psychological distress among college students [ 33 – 36 ].

Our results specifically showed that the frequency with which participants left their homes was significantly associated with stress and depression. Participants who left their homes every day had lower DASS-21 scores of stress, anxiety, and depression. Social relationships have been shown to give individuals a sense of purpose and greater appreciation for life, leading to overall reduced stress and bolstered mental health [ 37 – 39 ].

We have identified unique correlates of stress as they relate to the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, both sleeping hours and having a family member who tested positive for COVID-19 were correlates of stress. Changes in sleep and physical activity during the pandemic were associated with symptoms of high stress [ 40 , 41 ]. However, while previous studies have shown that patients with suspected COVID-19 (positive COVID-19 test result) demonstrated a significant reluctance to work [ 42 ], our study is among the first to identify the contribution of a family member’s positive test result.

This study shows a larger percentage of severe and extremely severe levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among female participants. In agreement with our results, previous studies established that the prevalence of anxiety was higher in women during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 43 – 46 ]. It has also been demonstrated that female students express greater concern for their future careers than do male students [ 47 ]. The dissimilarity in the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression between genders may be attributable to women seeking mental health consultation more often than men [ 48 ]. Being female was generally shown to be associated with a prominent increase in mental health problems during the pandemic [ 49 ].

This study found a significant discrepancy in hours devoted to sleep, extracurricular activities, and studying before and during the pandemic. The increase in hours of sleep could be due to heightened stress and anxiety about the pandemic during lockdown. The lockdown period had a negative impact on mental health by increasing post-traumatic stress symptoms and was associated with irregular sleep patterns [ 50 – 52 ]. Acute and chronic stress have been shown to perturb sleep differentially [ 53 ]. The observed decrease in hours spent on extracurricular activities during COVID-19 could be due to a fear of infection, as fear was a definite contributor to a reduction in pursuing activities and to an increase in anxiety during the pandemic [ 54 , 55 ]. As a whole, engagement in regular routines was also found to lower anxiety irrespective of the kind of stressor one was exposed to [ 56 ]. Therefore, one might be able to surmise that a lack of pursuing such activities may lead to greater anxiety. In discussing the motivation to pursue meaningful work, we found that students spent less hours studying when most instruction was conducted online. Although a decrease in hours of studying could be due to changing class syllabi and adjustments to the home environment, hours of studying did not correlate with stress, anxiety, or depression. It could be that students did not feel obligated to study in an environment with less structure or in the midst of a pandemic where students took on more responsibilities at home, such as caring for siblings or supporting their own children [ 57 , 58 ].

Future research should investigate current methods of mental health management for undergraduate students. The rise of telehealth and online counseling in the age of COVID-19 has provided greater opportunities for students to schedule appointments with a healthcare provider to manage mental health. Future studies might be able to explore the influence of telehealth on DASS-21 scores. Furthermore, it would be important to conduct follow up studies that investigate the impact of increased sleep on stress, anxiety, and depression during COVID-19. The adverse impact of the home environment should also be studied, specifically seeking to answer why students who left their homes less frequently experienced worsened mental health via higher DASS-21 scores (despite not dealing with the stresses of a daily commute, for instance).

Limitations

Because the survey was distributed during the lockdown period, an online convenience sampling method had to have been utilized. This sampling method limited the representativeness and generalizability of the findings reported, as we were necessarily constrained to only those responses from students with access to the Internet. Thus, it is not possible to draw causal inferences due to the nature of this study. The survey also had some duplicate questions and questions that did not provide the capability to select multiple options. For example, one question asked participants about COVID-19 safety precautions taken, where the selection of multiple options could have been appropriate. The term “extracurricular” was also left to the interpretation of participants. A better survey question could have offered participants the option to define extracurricular activities. Furthermore, in addition to DASS-21, the study could have benefited from the utilization of a resilience scale to examine how certain resilience factors could have protected individuals’ mental health from COVID-19 related stress. Allowing participants to evaluate resilience may have permitted greater insight into students’ mental health and wellbeing.

COVID-19 remains a credible threat to undergraduate students, beyond the acute and lingering physical effects of the virus. Students spent less time studying, complemented by the finding that the transition to remote learning hindered the majority of students’ academic experience. Students who left home more frequently may have had a greater opportunity to socialize, which lessened the stress and mental burden of lockdown. The majority of participants also stated that talking to family and engaging in favorite hobbies were beneficial for stress management. As such, these results showed that the pandemic led to significant changes in students’ academic performance, social life, and mental health.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Boston College Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Vice Provost for Research. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JN, MG, and WF contributed to the design, execution, and conceptualization of the study. JN and MG contributed to data management and conducted the literature search. MG contributed to the sample size methodology and carried out the survey distribution and initial data analysis. JN contributed to key elements of statistical analyses and interpretation with additional tests and further interpretation suggested by MG and WF. MG contributed to the essential prose of the manuscript with input from JN and WF. MG and JN prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. MG and JN created the figures and tables with input and suggestions from WF on appropriate edits to be made. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

- 1. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed (2020) 91(1):157–60. 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Mounsey R, Vandehey M, Diekhoff G. Working and Non-working university Students: Anxiety, Depression, and Grade point Average. Coll Student J (2013) 47(2):379. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Krieg D. High Expectations for Higher Education? Perceptions of College and Experiences of Stress Prior to and through the College Career. Coll Student J (2013) 47(4):635. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Dyson R, Renk K. Freshmen Adaptation to university Life: Depressive Symptoms, Stress, and Coping. J Clin Psychol (2006) 62(10):1231–44. 10.1002/jclp.20295 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Beck R, Taylor C, Robbins M. Missing home: Sociotropy and Autonomy and Their Relationship to Psychological Distress and Homesickness in College Freshmen. Anxiety Stress Coping (2003) 16(2):155–66. 10.1080/10615806.2003.10382970 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Reifman A, Arnett JJ, Colwell MJ. Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Assessment and Application. J Youth Dev (2007) 2(1):37–48. 10.5195/jyd.2007.359 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Murphy L, Denis R, Ward CP, Tartar JL. Academic Stress Differentially Influences Perceived Stress, Salivary Cortisol, and Immunoglobulin-A in Undergraduate Students. Stress (2010) 13(4):365–70. 10.3109/10253891003615473 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Doron J, Stephan Y, Boiché J, Scanff CL. Coping with Examinations: Exploring Relationships between Students' Coping Strategies, Implicit Theories of Ability, and Perceived Control. Br J Educ Psychol (2009) 79(3):515–28. 10.1348/978185409X402580 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Kecojevic A, Basch CH, Sullivan M, Davi NK. The Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on Mental Health of Undergraduate Students in New Jersey, Cross-Sectional Study. PloS one (2020) 15(9):e0239696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239696 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Huckins JF, DaSilva AW, Wang W, Hedlund E, Rogers C, Nepal SK, et al. Mental Health and Behavior of College Students during the Early Phases of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Smartphone and Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. J Med Internet Res (2020) 22(6):e20185. 10.2196/20185 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res (2020) 22(9):e22817. 10.2196/22817 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Wyatt T, Oswalt SB. Comparing Mental Health Issues Among Undergraduate and Graduate Students. Am J Health Educ (2013) 44(2):96–107. 10.1080/19325037.2013.764248 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Mowbray CT, Mandiberg JM, Stein CH, Kopels S, Curlin C, Megivern D, et al. Campus Mental Health Services: Recommendations for Change. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2006) 76(2):226–37. 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.226 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic Stress in the Age of COVID-19: A Call to Close Critical Gaps and Adapt to New Realities. Psychol Trauma (2020) 12(4):331–5. 10.1037/tra0000592 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Suliman WA, Abu-Moghli FA, Khalaf I, Zumot AF, Nabolsi M. Experiences of Nursing Students under the Unprecedented Abrupt Online Learning Format Forced by the National Curfew Due to COVID-19: A Qualitative Research Study. Nurse Educ Today (2021) 100:104829. 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104829 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Saha A, Dutta A, Sifat RI. The Mental Impact of Digital divide Due to COVID-19 Pandemic Induced Emergency Online Learning at Undergraduate Level: Evidence from Undergraduate Students from Dhaka City. J Affect Disord (2021) 294:170–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.045 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Understanding Adolescent's Sleep Patterns and School Performance: a Critical Appraisal. Sleep Med Rev (2003) 7(6):491–506. 10.1016/s1087-0792(03)90003-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A, Castronovo V, Mombelli S, Bottoni D, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Sleep Quality in university Students and Administration Staff. J Neurol (2021) 268(1):8–15. 10.1007/s00415-020-10056-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Blume C, Schmidt MH, Cajochen C. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Human Sleep and Rest-Activity Rhythms. Curr Biol (2020) 30(14):R795-R797–7. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.021 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Zhang Y, Wang D, Zhao J, Xiao-Yan CH, Chen H, Ma Z, et al. Insomnia and Other Sleep-Related Problems during the Remission Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Large-Scale Survey Among College Students in China. Psychiatry Res (2021) 304:114153. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114153 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Evans S, Alkan E, Bhangoo JK, Tenenbaum H, Ng-Knight T. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Mental Health, Wellbeing, Sleep, and Alcohol Use in a UK Student Sample. Psychiatry Res (2021) 298:113819. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Oh H, Marinovich C, Rajkumar R, Besecker M, Zhou S, Jacob L, et al. COVID-19 Dimensions Are Related to Depression and Anxiety Among US College Students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. J Affect Disord (2021) 292:270–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Luong R, Lomanowska AM. Evaluating Reddit as a Crowdsourcing Platform for Psychology Research Projects. Teach Psychol (2021) 49:329–37. 10.1177/00986283211020739 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Jamnik MR, Lane DJ. The Use of Reddit as an Inexpensive Source for High-Quality Data. Pract Assess Res Eval (2017)(1). [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Lee JY, Chang OD, Ammari T. Using Social media Reddit Data to Examine foster Families’ Concerns and Needs during COVID-19. Child Abuse Negl (2021) 121:105262. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105262 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther (1995) 33(3):335–43. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Henry JD, Crawford JR. The Short-form Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct Validity and Normative Data in a Large Non-clinical Sample. Br J Clin Psychol (2005) 44(2):227–39. 10.1348/014466505X29657 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Ng F, Trauer T, Dodd S, Callaly T, Campbell S, Berk M. The Validity of the 21-item Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales as a Routine Clinical Outcome Measure. Acta Neuropsychiatr (2007) 19(5):304–10. 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2007.00217.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a Sample of College Students. J Affect Disord (2015) 173:90–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Lischer S, Safi N, Dickson C. Remote Learning and Students’ Mental Health during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Method Enquiry. Prospects (2021) 51:589–99. 10.1007/s11125-020-09530-w [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Watermeyer R, Crick T, Knight C, Goodall J. COVID-19 and Digital Disruption in UK Universities: Afflictions and Affordances of Emergency Online Migration. High Educ (2021) 81:623–41. 10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Mukhtar K, Javed K, Arooj M, Sethi A. Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic Era. Pak J Med Sci (2020) 36(COVID19-S4):S27-S31. 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2785 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Brenneisen Mayer F, Souza Santos I, Silveira PSP, Itaqui Lopes MH, de Souza ARND, Campos EP, et al. Factors Associated to Depression and Anxiety in Medical Students: a Multicenter Study. BMC Med Educ (2016) 16(1):282. 10.1186/s12909-016-0791-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Islam S, Akter R, Sikder T, Griffiths MD. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Depression and Anxiety Among First-Year university Students in Bangladesh: a Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Ment Health Addict (2020) 20:1289–302. 10.1007/s11469-020-00242-y [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Saeed H, Saleem Z, Ashraf M, Razzaq N, Akhtar K, Maryam A, et al. Determinants of Anxiety and Depression Among university Students of Lahore. Int J Ment Health Addict (2018) 16(5):1283–98. 10.1007/s11469-017-9859-3 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. ul Haq MA, Dar IS, Aslam M, Mahmood QK. Psychometric Study of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among university Students. J Public Health (2018) 26:211–7. 10.1007/s10389-017-0856-6 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Cohen S. Social Relationships and Health. Am Psychol (2004) 59(8):676–84. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Thoits PA. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. J Health Soc Behav (2011) 52(2):145–61. 10.1177/0022146510395592 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]