Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Last »

- South Asian Studies Follow Following

- Indian studies Follow Following

- South Asia Follow Following

- Hinduism Follow Following

- Indology Follow Following

- Indian Politics Follow Following

- Sanskrit language and literature Follow Following

- History of India Follow Following

- South Asian History Follow Following

- India (Anthropology) Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Journals

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Substance use and addiction research in India

Pratima murthy, n manjunatha, prabhat kumar chand, vivek benegal.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Pratima Murthy, Department of Psychiatry, De-Addiction Centre, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore - 560 029, India [email protected]

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Substance use patterns are notorious for their ability to change over time. Both licit and illicit substance use cause serious public health problems and evidence for the same is now available in our country. National level prevalence has been calculated for many substances of abuse, but regional variations are quite evident. Rapid assessment surveys have facilitated the understanding of changing patterns of use. Substance use among women and children are increasing causes of concern. Preliminary neurobiological research has focused on identifying individuals at high risk for alcohol dependence. Clinical research in the area has focused primarily on alcohol and substance related comorbidity. There is disappointingly little research on pharmacological and psychosocial interventions. Course and outcome studies emphasize the need for better follow-up in this group. While lack of a comprehensive policy has been repeatedly highlighted and various suggestions made to address the range of problems caused by substance use, much remains to be done on the ground to prevent and address these problems. It is anticipated that substance related research publications in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry will increase following the journal having acquired an ‘indexed’ status.

Keywords: Alcohol, drugs, India, research, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Substance use has been a topic of interest to many professionals in the area of health, particularly mental health. An area with enormous implications for public health, it has generated a substantial amount of research. In this paper we examine research in India in substance use and related disorders. Substance use includes the use of licit substances such as alcohol, tobacco, diversion of prescription drugs, as well as illicit substances.

METHODOLOGY

For this review, we have carried out a systematic web-based review of the Indian Journal of Psychiatry (IJP). The IJP search included search of both the current and archives section and an issue-to-issue search of articles with any title pertaining to substance use. This has included original articles, reviews, case series and reports with significant implications. Letters to editor and abstracts of annual conference presentations have not been included.

Publications in other journals were accessed through a Medlar search (1992-2009) and a Pubmed search (1950-2009). Other publications related to substance use available on the websites of international and national agencies have also been reviewed. In this review, we focus mainly on publications in the IJP and have selectively reviewed the literature from other sources.

For the sake of convenience, we discuss the publications under the following areas: Epidemiology, clinical issues (diagnosis, psychopathology, comorbidity), biological studies (genetics, imaging, electrophysiology, and vulnerability), interventions and outcomes as well as community interventions and policies. There is a vast amount of literature on tobacco use and consequences in international and national journals, but this is outside the scope of this review. Tobacco is mentioned in this review of substance use to highlight that it should be remembered as the primary licit substance of abuse in our country.

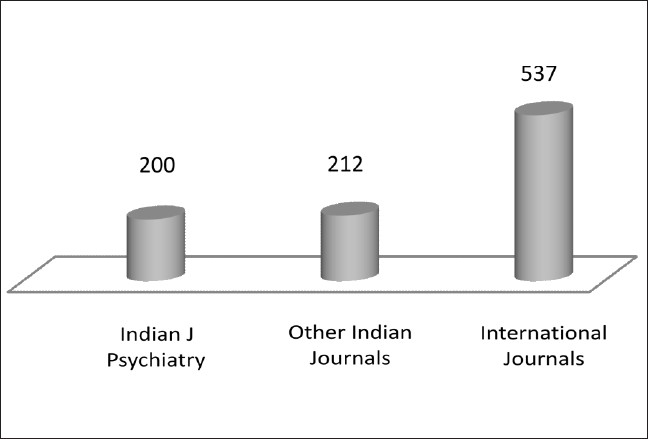

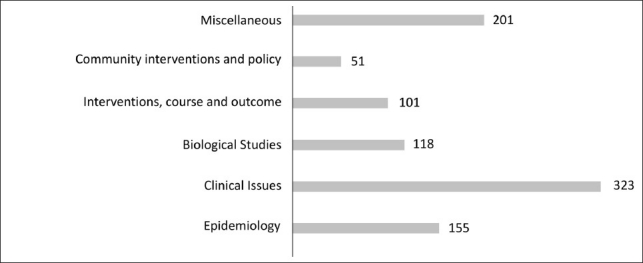

The number of articles (area wise) available from IJP, other Indian journals and international journals are indicated in Figures 1 and 2 . A majority of the publications in international journals relate to tobacco, substance use co-morbidity and miscellaneous areas like animal studies.

Publications in the area of substance use and related disorders

Break up of areas of publication

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Much of the earlier epidemiological research has been regional and it has been very difficult to draw inferences of national prevalence from these studies.

Regional studies

Studies between 1968 until 2000 have been primarily on alcohol use [ Table 1 ]. They have varied in terms of populations surveyed (ranged from 115 to 16,725), sampling procedures (convenient, purposive and representative), focus of enquiry (alcohol use, habitual excessive use, alcohol abuse, alcoholism, chronic alcoholism, alcohol and drug abuse and alcohol dependence), location (urban, rural or both, Slums), in the screening instruments used (survey questionnaires and schedules, semi-structured interviews, quantity frequency index, Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) etc). Alcohol ‘use/abuse’ prevalence in different regions has thus varied from 167/1000 to 370/1000; ‘alcohol addiction’ or ‘alcoholism’ or ‘chronic alcoholism’ from 2.36/1000 to 34.5/1000; alcohol and drug use/abuse from 21.4 to 28.8/1000. A meta-analysis by Reddy and Chandrashekhar[ 26 ] (1998) revealed an overall substance use prevalence of 6.9/1000 for India with urban and rural rates of 5.8 and 7.3/1000 population. The rates among men and women were 11.9 and 1.7% respectively.

Regional epidemiological studies in substance use: A summary

U - Urban; R - Rural; Sl - Slum; SR - Semi-rural; NM - Not mentioned

Regional studies between 2001 and 2007 continue to reflect this variability. Currently, the interest is to look at hazardous alcohol use. A study in southern rural India[ 27 ] showed that 14.2% of the population surveyed had hazardous alcohol use on the AUDIT. A similar study in the tertiary hospital[ 28 ] showed that 17.6% admitted patients had hazardous alcohol use.

The only incidence study on alcohol use from Delhi[ 17 ] found that annual incidence of nondependent alcohol use and dependent alcohol use among men was 3 and 2 per 1000 persons in a total cohort of 2,937 households.

National Studies

The National Household Survey of Drug Use in the country[ 29 ] is the first systematic effort to document the nation-wide prevalence of drug use [ Table 2 ]. Alcohol (21.4%) was the primary substance used (apart from tobacco) followed by cannabis (3.0%) and opioids (0.7%). Seventeen to 26% of alcohol users qualified for ICD 10 diagnosis of dependence, translating to an average prevalence of about 4%. There was a marked variation in alcohol use prevalence in different states of India (current use ranged from a low of 7% in the western state of Gujarat (officially under Prohibition) to 75% in the North-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh. Tobacco use prevalence was high at 55.8% among males, with maximum use in the age group 41-50 years.

Nationwide studies on substance use prevalence

H-H - House to house survey; M - Male; F - Female; A - Alcohol, C - Cannabis; O - Opioids; T - Tobacco

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS)[ 30 ] provides some insights into tobacco and alcohol use. The changing trends between NFHS 2 and NFHS 3 reflect an increase in alcohol use among males since the NFHS 2, and an increase in tobacco use among women.

The Drug Abuse Monitoring System,[ 29 ] which evaluated the primary substance of abuse in inpatient treatment centres found that the major substances were alcohol (43.9%), opioids (26%) and cannabis (11.6%).

Patterns of substance use

Rapid situation assessments (RSA) are useful to study patterns of substance use. An RSA by the UNODC in 2002[ 31 ] of 4648 drug users showed that cannabis (40%), alcohol (33%) and opioids (15%) were the major substances used. A Rapid Situation and Response Assessment (RSRA) among 5800 male drug users[ 32 ] revealed that 76% of the opioid users currently injected buprenorphine, 76% injected heroin, 70% chasing and 64% using propoxyphene. Most drug users concomitantly used alcohol (80%). According to the World Drug Report,[ 33 ] of 81,802 treatment seekers in India in 2004-2005, 61.3% reported use of opioids, 15.5% cannabis, 4.1% sedatives, 1.5% cocaine, 0.2% amphetamines and 0.9% solvents.

Special populations

In the last decade, there has been a shift in viewing substance use and abuse as an exclusive adult male phenomenon to focusing on the problem in other populations. In the GENACIS study[ 34 ] covering a population of 2981 respondents [1517 males; 1464 females], across five districts of Karnataka, 5.9% of all female respondents (N =87) reported drinking alcohol at least once in the last 12 months, compared to 32.7% among male respondents (N = 496). Special concerns with women’s drinking include the fetal alcohol spectrum effects described with alcohol use during pregnancy.[ 35 ]

Abuse of other substances among women has largely been studied through Rapid Assessment Surveys. A survey of 1865 women drug users by 110 NGOs across the country[ 36 ] revealed that 25% currently were heroin users, 18% used dextropropoxyphene, 11% opioid containing cough syrups and 7% buprenorphine. Eighty seven per cent concomitantly used alcohol and 83% used tobacco. Twenty five per cent of respondents had lifetime history of injecting drug use and 24% had been injecting in the previous month. There are serious sexually transmitted disease risks, including HIV that women partners and drug users face.[ 36 , 37 ]

Substance use in medical fraternity

As early as 1977, a drug abuse survey in Lucknow among medical students revealed that 25.1% abused a drug at least once in a month. Commonly abused drugs included minor tranquilizers, alcohol, amphetamines, bhang and non barbiturate sedatives. In a study of internees on the basis of a youth survey developed by the WHO in 1982,[ 38 ] 22.7% of males ‘indulged in alcohol abuse’ at least once in a month, 9.3% abused cannabis, followed by tranquilizers. Common reasons cited were social reasons, enjoyment, curiosity and relief from psychological stress. Most reported that it was easy to obtain drugs like marijuana and amphetamines. Substance use among medical professionals has become the subject of recent editorials.[ 39 , 40 ]

Substance use among children

The Global Youth Tobacco Survey[ 41 ] in 2006 showed that 3.8% of students smoke and 11.9% currently used smokeless tobacco. Tobacco as a gateway to other drugs of abuse has been the topic of a symposium.[ 42 ]

A study of 300 street child laborers in slums of Surat in 1993[ 43 ] showed that 135 (45%) used substances. The substances used were smoking tobacco, followed by chewable tobacco, snuff, cannabis and opioids. Injecting drug use[ 44 ] is also becoming apparent among street children as are inhalants.[ 45 ]

A study in the Andamans[ 46 ] shows that onset of regular use of alcohol in late childhood and early adolescence is associated with the highest rates of consumption in adult life, compared to later onset of drinking.

Studies in other populations

A majority of 250 rickshaw pullers interviewed in New Delhi[ 47 ] in 1986 reported using tobacco (79.2%), alcohol (54.4%), cannabis (8.0%) and opioids (0.8%). The substances reportedly helped them to be awake at night while working. In a study of prevalence of psychiatric illness in an industrial population[ 48 ] in 2007, harmful use/dependence on substances (42.83%) was the most common psychiatric condition. A study among industrial workers from Goa on hazardous alcohol use using the AUDIT and GHQ 12 estimated a prevalence of 211/1000 with hazardous drinking.[ 19 ]

Hospital-based studies

These studies have basically described profiles of substance use among patients and include patterns of alcohol use,[ 49 – 53 ] opioid use,[ 54 – 56 ] pediatric substance use,[ 57 ] female substance use,[ 58 ] children of alcoholics[ 59 ] and geriatric substance use.[ 60 ]

Alcohol misuse has been implicated in 20% of brain injuries[ 61 ] and 60% of all injuries in the emergency room setting.[ 62 ] In a retrospective study of emergency treatment seeking in Sikkim between 2000 and 2005,[ 63 ] substance use emergencies constituted 1.16% of total psychiatric emergencies. Alcohol withdrawal was the commonest cause for reporting to the emergency (57.4%).

Effects of substance use disorders

Mortality and morbidity due to alcohol and tobacco have been extensively reviewed elsewhere[ 35 , 64 – 66 ] and are beyond the scope of this review. The effects of cannabis have also been reviewed.[ 67 ] Mortality with injecting drug use is a serious concern with increase in crude mortality rates to 4.25 among injecting drug users compared to the general population.[ 68 ] Increased susceptibility to HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases has been reported with alcohol[ 69 ] as well as injecting drug use.[ 70 ]

Clinical issues

Harmful alcohol use patterns among admitted patients in general hospital has highlighted the importance of routine screening and intervention in health care settings.[ 71 ]

Peer influence is a significant factor for heroin initiation.[ 72 ] Precipitants of relapse (dysfunction, stress and life events) differ among alcohol and opioid dependents.[ 73 ] Chronologies in the development of dependence have been evaluated in alcohol dependence.[ 74 , 75 ]

Craving a common determinant of relapse has been shown to reduce with increase in length of period of abstinence.[ 76 ]

Alcohol dependence constitutes a significant group among the psychiatric population in the Armed Forces.[ 77 ] A study of personality factors[ 78 ] among 100 alcohol dependent persons showed significantly high neuroticism, extroversion, anxiety, depression, psychopathic deviation, stressful life events and significantly low self-esteem as compared with normal control subjects. Alcohol dependence causes impairment in set shifting, visual scanning and response inhibition abilities and relative abstinence has been found to improve this deficit.[ 79 , 80 ] Alcohol use has had a significant association with head injury and cognitive deficits.[ 81 , 82 ] Persistent drinking is associated with persisting memory deficits in head injured alcohol dependent patients.[ 82 ] Mild intellectual impairment has been demonstrated in patients with bhang and ganja dependence.[ 83 – 86 ]

Kumar and Dhawan[ 87 ] found that health related reasons like death/physical complications due to drug use in peers and patients themselves, knowledge of HIV and difficulties in accessing veins were the main reason for reverse transition (shift from parenteral to inhalation route).

Evaluation and assessment

Diagnostic issues have focused on cross-system agreement[ 88 ] between ICD-10 and DSM IV, variability in diagnostic criteria across MAST, RDC, DSM and ICD[ 89 ] and suitability of MAST as a tool for detecting alcoholism.[ 90 ] The CIWA-A was found useful in monitoring alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[ 91 ]

The utility of liver functions for diagnosis of alcoholism and monitoring recovery has been demonstrated in clinical settings.[ 92 – 94 ] A range of hepatic dysfunction has been demonstrated through liver biopsies.[ 95 ]

A few studies have focused on scale development for motivation[ 96 , 97 ] and addiction related dysfunction[ 98 ] (Brief Addiction Rating Scale). An evaluation of two psychomotor tests comparing smokers and non-smokers found no differences across the two groups.[ 99 ]

Typology research has included validation of Babor’s[ 100 ] cluster A and B typologies, age of onset typology,[ 101 ] and a review on typology of alcoholism.[ 102 ]

Craving plays an important role in persistence of substance use and relapse. Frequency of craving has been shown to decrease with increase in length of abstinence among heroin dependent patients. Socio-cultural factors did not influence the subjective experience of craving.[ 76 ]

In a study of heroin dependent patients, their self-report moderately agreed with urinalysis using thin layer chromatography (TLC), gas liquid chromatography (GLC) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).[ 103 ] The authors, however, recommend that all drug dependence treatment centers have facilities for drug testing in order to validate self-report.

Comorbidity/dual diagnosis

Cannabis related psychopathology has been a favorite topic of enquiry in both retrospective[ 104 , 105 ] and prospective studies[ 106 ] and vulnerability to affective psychosis has been highlighted. The controversial status of a specific cannabis withdrawal syndrome and cannabis psychosis has been reviewed.[ 67 ]

High life time prevalence of co-morbidity (60%) has been demonstrated among both opioid and alcohol dependent patients.[ 107 ] In alcohol dependence, high rates of depression and cluster B personality disorders[ 54 , 108 ] and phobia[ 109 ] have been demonstrated, but the need to revaluate for depressive symptoms after detoxification has been highlighted.[ 110 ] It is necessary to evaluate for ADHD, particularly in early onset alcohol dependent patients.[ 111 ] Seizures are overrepresented in subjects with alcohol and merit detailed evaluation.[ 112 ] Delirium and convulsions can also complicate opioid withdrawal states.[ 113 , 114 ] Skin disease,[ 115 ] and sexual dysfunction[ 116 ] have also been the foci of enquiry. Phenomenological similarities between alcoholic hallucinosis and paranoid schizophrenia have been discussed.[ 117 ] Opioid users with psychopathology[ 118 ] have diverse types of psychopathology as do users of other drugs.[ 119 ]

In a study of 22 dual diagnosed schizophrenia patients, substance use disorder preceded the onset of schizophrenic illness in the majority.[ 120 ] While one study found high rates of comorbid substance use (54%) in patients with schizophrenia with comorbid substance users showing more positive symptoms[ 121 ] which remitted more rapidly in the former group,[ 122 ] other studies suggest that substance use comorbidity in schizophrenia is low, and is an important contributor to better outcome in schizophrenia in developing countries like India.[ 123 , 124 ]

The diagnosis and management of dual diagnosis has been reviewed in detail.[ 125 ]

Social factors

Co-dependency has been described in spouses of alcoholics and found to correlate with the Addiction Severity scores of their husbands.[ 126 ] Coping behavior described among wives of alcoholics include avoidance, indulgence and fearful withdrawal.[ 127 ] These authors did not find any differences in personality between wives of alcoholics compared to controls.[ 128 ] Delusional jealousy and fighting behavior of substance abusers/dependents are important determinants of suicidal attempts among their spouses.[ 129 ] Parents of narcotic dependent patients, particularly mothers also show significant distress.[ 130 ]

BIOLOGY OF ADDICTION

An understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence has led to a reformulation of the etiology of this complex disorder.[ 131 ] An understanding of specific neurotransmitter systems has led to the development of specific pharmacotherapies for these disorders.

Cellular and molecular mechanisms

Altered alcohol metabolism due to polymorphisms in the alcohol metabolizing enzymes may influence clinical and behavioral toxicity due to alcohol. Erythrocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase was demonstrated to be suitable as a peripheral trait marker for alcohol dependence.[ 132 ] Single nucleotide polymorphism of the ALDH 2 gene has been studied in six Indian populations and provides the baseline for future studies in alcoholism.[ 133 ] An evaluation of ADH 1B and ALDH 2 gene polymorphism in alcohol dependence showed a high frequency of the ALDH2*2/*2 genotype among alcohol-dependent subjects.[ 134 ] DRD2 polymorphisms have been studied in patients with alcohol dependence, but a study in an Indian population failed to show a positive association. Genetic polymorphisms of the opioid receptor µ1 has been associated with alcohol and heroin addiction in a population from Eastern India.[ 135 ]

Neuro-imaging and electrophysiological studies

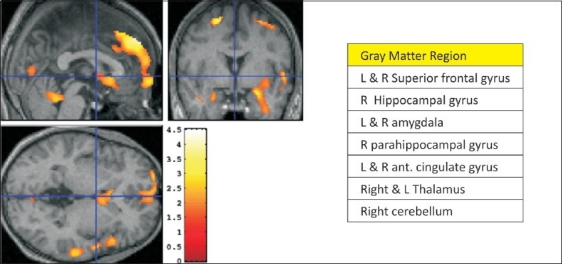

Certain individuals may develop early and severe problems due to alcohol misuse and be poorly responsive to treatment. Such vulnerability has been related to individual differences in brain functioning [ Figure 3 ]. Individuals with a high family history of alcoholism (specifically of the early-onset type, developing before 25 years of age) display a cluster of disinhibited behavioral traits, usually evident in childhood and persisting into adulthood.[ 136 ]

Brain volume differences between children and adolescents at high risk and low risk for alcohol dependence

Early onset drinking may be influenced by delayed brain maturation. Alcohol-naïve male offspring of alcohol-dependent fathers have smaller (or slowly maturing) brain volumes compared to controls in brain areas responsible for attention, motivation, judgment and learning.[ 137 , 138 ] The lag is hypothesized to work through a critical function of brain maturation-perhaps delayed myelination (insulation of brain pathways).

Functionally, this is thought to create a state of central nervous system hyperexcitability or disinhibition.[ 139 ] Individuals at risk have also been shown to have specific electro-physiological characteristics such as reduced amplitude of the P300 component of the event related potential.[ 140 , 141 ] Auditory P300 abnormalities have also been demonstrated among opiate dependent men and their male siblings.[ 142 ]

Such brain disinhibition is manifest by a spectrum of behavioral abnormalities such as inattention (low boredom thresholds), hyperactivity, impulsivity, oppositional behaviors and conduct problems, which are apparent from childhood and persist into adulthood. These brain processes not only promote impulsive risk-taking behaviors like early experimentation with alcohol and other substances but also appear to increase the reinforcement from alcohol while reducing the subjective appreciation of the level of intoxication, thus making it more likely that these individuals are likely not only to start experimenting with alcohol use at an early age but are more likely to have repeated episodes of bingeing.[ 143 ]

INTERVENTIONS, COURSE AND OUTCOME

Although there are a few review articles on pharmacological treatment of alcoholism,[ 144 , 145 ] there is a dearth of randomized studies on relapse prevention treatment in our setting.

Treatment of complications of substance use has been confined to case reports. A case report of thiamine resistant Wernicke Korsakoff Syndrome[ 146 ] successfully treated with a combination of magnesium sulphate and thiamine. Another case of subclinical psychological deterioration[ 147 ] (alcoholic dementia) improved with thiamine and vitamin B supplementation.

Pharmacological intervention

A randomized double blind study compared the effectiveness of detoxification with either lorazepam or chlordiazepoxide among hundred alcohol dependent inpatients with simple withdrawal. Lorazepam was found to be as effective as the more traditional drug chlordiazepoxide in attenuating alcohol withdrawal symptoms as assessed using the revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale.[ 148 ] This has implications for treatment in peripheral settings where liver function tests may not be available. However, benzodiazepines must be used carefully and monitored as dependence is very common.[ 149 ]

In a study closer to the real-world situation from Mumbai, 100 patients with alcohol dependence with stable families were randomized to receive disulfiram or topiramate. At the end of nine months, though patients on topiramate had less craving, a greater proportion of patients on disulfiram were abstinent (90% vs. 56%). Patients in the disulfiram group also had a longer time to their first drink and relapse.[ 150 ] Similar studies by the same authors and with similar methodology had earlier found that disulfiram was superior to acamprosate and Naltrexone. Though the study lacked blinding, it had an impressively low (8%) dropout rate.[ 151 , 152 ] A chart based review has shown there was no significant difference with regard to abstinence among the patients prescribed acamprosate, naltrexone or no drugs. Although patients on acamprosate had significantly better functioning, lack of randomization and variations in base line selection parameters may have influenced these findings.[ 153 ] Short term use of disulfiram among alcohol dependence patients with smoking was not associated with decrease pulmonary function test (FEV 1 ) and airway reactivity.[ 154 ]

Usefulness of clonidine for opioid detoxification has been described by various authors. These studies date back to 1980 when there was no alternative treatment for opioid dependence and clonidine emerged as the treatment of choice for detoxification in view of its anti adrenergic activity.[ 155 – 157 ] Sublingual buprenorphine for detoxification among these patients was reported as early as 1992. At that time the dose used was much lower, i.e. 0.6 -1.2 mg/ day which is in contrast to the current recommended dose of 6-16 mg/day. Comparison of buprenorphine (0.6-1.2 mg/ day) and clonidine (0.3-0.9 mg/day) for detoxification found no difference among treatment non completers. Maximum drop out occurred on the fifth day when withdrawal symptoms were very high.[ 158 ] A 24- week outcome study of buprenorphine maintenance in opiate users showed high retention rates of 81.5%, reduction in Addiction Severity Index scores and injecting drug use. Use of slow release oral morphine for opioid maintenance has also been reported.[ 159 ] Effectiveness of baclofen in reducing withdrawal symptoms among three patients with solvent dependence is reported.[ 160 ]

Psychosocial

Psychoeducational groups have been found to facilitate recovery in alcohol and drug dependence.[ 161 ] Family intervention therapy in addition to pharmacotherapy was shown to reduce the severity of alcohol intake and improve the motivation to stop alcohol in a case-control design study.[ 162 ] Several community based models of care have been developed with encouraging results.[ 163 ]

Course and outcome

An evaluation after five years, of 800 patients with alcohol dependence treated at a de-addiction center, found that 63% had not utilized treatment services beyond one month emphasizing the need to retain patients in follow-up.[ 164 ]

In a follow-up study on patients with alcohol dependence, higher income and longer duration of in-patient treatment were found to positively correlate with improved outcome at three month follow up. Outcome data was available for 52% patients; 81% of those maintained abstinence.[ 165 ] Maximum attrition was between three to six months. In a similar study among in-patients, 46% were abstinent. The drop out rate was 10% at the end of one year.[ 101 ] Studies done in the community setting have shown the effectiveness of continued care in predicting better outcome in alcohol dependence. In one study the patient group from a low socio-economic status who received weekly follow up or home visit at a clinic located within the slum showed improvement at the end of month 3, 6 and 9, and one year, in comparison with a control group that received no active follow-up intervention.[ 166 ] In a one-year prospective study of outcome following de-addiction treatment, poor outcome was associated with higher psychosocial problems, family history of alcoholism and more follow-up with mental health services.[ 167 ]

COMMUNITY INTERVENTIONS AND POLICIES

The camp approach for treatment of alcohol dependence was popularized by the TTK hospital camp approach at Manjakkudi in Tamil Nadu.[ 168 ] Treatment of alcohol and drug abuse in a camp setting as a model of drug de-addiction in the community through a 10 day camp treatment was found to have good retention rates and favorable outcome at six months.

Community perceptions of substance related problems are useful to understand for policy development. In a 1981 study in urban and rural Punjab of 1031 respondents, 45% felt people could not drink without producing bad effects on their health, 26.2% felt they could have one or two drinks per month without affecting their health. About one third felt it was alright to have one or two drinks on an occasion. 16.9% felt it was normal to drink ‘none at all’. Alcoholics were identified by behavior such as being dead drunk, drinking too much, having arguments and fights and creating public nuisance. Current users gave the most permissive responses and non-users the most restrictive responses regarding the norms for drinking.[ 169 ] The influence of cultural norms[ 170 ] has led the tendency to view drugs as ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

Simulations done in India have demonstrated that implementing a nationwide legal drinking age of 21 years in India, can achieve about 50-60 % of the alcohol consumption reducing effects compared to prohibition.[ 171 ] However, recently there are attempts to increase the permissible legal alcohol limit. This kind of contrarian approach does not make for coherent policy.

It has been argued that the 1970s saw an overzealous implementation of a simplistic model of supply and demand.[ 171 ] A presidential address[ 172 ] in 1991 emphasized the need for a multipronged approach to addressing alcohol-related problems. Existing programs have been identified as being patchy, poorly co-ordinated and poorly funded. Primary, secondary and tertiary approaches were discussed. The address highlighted the need for supply and demand side measures to address this significant public health problem. It highlighted the political and financial power of the alcohol industry and the social ambivalence to drinking. More recently, the need to have interventions for harmful and hazardous use, the need to develop evidence based combinations of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions and stepped care solutions have been highlighted.[ 173 ] Standard treatment guidelines for alcohol and other drug use disorders have suggested specific measures at the primary, secondary and tertiary health care level, including at the solo physician level.[ 174 ] An earlier report in 1988 on training general practitioners on management of alcohol related problems[ 175 ] suggests that their involvement in alcohol and health education was modest, involvement in control and regulatory activities minimal, and they perceived no role in the development of a health and alcohol policy.

There have been reviews of the National Master Plan 1994, which envisaged different responsibilities for the Ministries of Health and the Ministry of Welfare (presently Social Justice and Empowerment) and the Drug Dependence Program 1996.[ 176 , 177 ] A proposal for adoption of a specialty section on addiction medicine[ 178 ] includes the development of a dedicated webpage, co-ordinated CMEs, commissioning of position papers, promoting demand reduction strategies and developing a national registry.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

While epidemiological research has now provided us with figures for national-level prevalence, it would be prudent to recognize that there are regional differences in substance use prevalence and patterns. It is also prudent to recognize the dynamic nature of substance use. There is thus a need for periodic national surveys to determine changing prevalence and incidence of substance use. Substance use is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Substance use among women and children is increasingly becoming the focus of attention and merits further research. Pharmaceutical drug abuse and inhalant use are serious concerns. For illicit drug use, rapid assessment surveys have provided insights into patterns and required responses. Drug related emergencies have not been adequately studied in the Indian context.

Biological research has focused on two broad areas, neurobiology of vulnerability and a few studies on molecular genetics. There is a great need for translation research based on the wider body of basic and animal research in the area.

Clinical research has primarily focused on alcohol. An area which has received relatively more attention in substance related comorbidity. There is very little research on development and adaptation of standardized tools for assessment and monitoring, and a few family studies. Ironically, though several evidence based treatments have now become available in the country, there are very few studies examining the utilization and effectiveness of these treatments, given that most treatment is presently unsubsidized and dependent on out of pocket expenditure. Both pharmacological and psychosocial interventions have disappointingly attracted little research. Course and outcome studies emphasize the need for better follow-up in this group.

While a considerable number of publications have lamented the lack of a coherent policy, the need for human resource enhancement and professional training and recommended a stepped-care multipronged approach, much remains to be done on the ground.

Finally, publication interest in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry in the area of substance use will undoubtedly increase, with the journal having become indexed.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

- 1. Gopinath PS. Epidemiology of mental illness in Indian village. Prevalence survey for mental illness and mental deficiency in Sakalawara (MD thesis) 1968 [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Elnagar MN, Maitra P, Rao MN. Mental health in an Indian rural community. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:499–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.546.499. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Dube KC, Handa SK. Drug use in health and mental illness in an Indian population. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:345–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.544.345. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Varghese A, Beig A, Senseman LA, Rao SS, Benjamin A social and psychiatric study of a representative group of families in Vellore town. Indian J Med Res. 1973;61:608–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Thacore VR. Drug-abuse in India with special reference to Lucknow. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:257–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Nandi D.N, Ajmany S, Ganguli H, Benerjee G, Boral G.C, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, et al. Psychiatric disorders in a rural community in West Bengal An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Lal B, Singh G. Drug abuse in Punjab. Br J Addict. 1979;74:441–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1979.tb01370.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Sethi BB, Trivedi JK. Drug abuse in rural population. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;21:211–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Varma VK, Singh A, Singh S, Malhotra AK. Extent and pattern of alcohol use in North India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:331–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ponnudorai R, Jayakar J, Raju B, Pattamuthu R. An epidemiological study of alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:176–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Premranjan KC, Danabalan M, Chandrasekhar R, Srinivasa DK. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in an urban community of Pondicherry. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:99–102. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Jena R, Shukla TR, Pal H. Drug abuse in a rural community in Bihar: Some psychosocial correlates. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:43–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Ghulam R, Rahman I, Naqi S, Gupta SR. An epidemiological study of drug abuse in urban population of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:160–5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Singh RB, Ghosh S, Niaz MA, Rastogi V, Wander GS. Validation of tobacco and alcohol intake questionnaire in relation to food intakes for the five city study and proposed classification for indians. J Physicians India. 1998;46:587–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Hazarika NC, Biswas D, Phukan RK, Hazarika D, Mahanta J. Prevalence and pattern of substance abuse at bandardewa, a border area of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:262–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Sharma S, Singh MM. Prevalence of mental disorders: An epidemiological study In Goa. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:118–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Mohan D, Chopra A, Sethi H. Incidence estimates of substance use disorders in a cohort from Delhi, India. Indian J Med Res. 2002;115:128–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Meena, Khanna P, Vohra AK, Rajput R. Prevalence and pattern of alcohol and substance abuse in urban areas of Rohtak city. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:348–52. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chagas Silva M, Gaunekar G, Patel V, Kukalekar DS, Fernandes J. The prevalence and correlates of hazardous drinking in industrial workers: A community study from Goa India. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:79–83. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Gupta PC, Saxena S, Pednekar M. Alcohol consumption among middle-aged and elderly men: A community study from Western India. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:327–31. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg077. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Benegal V, Gururaj G, Murthy P. Report on a WHO Collaborative Project on Unrecorded Consumption of Alcohol in Karnataka, India. Bangalore, India: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Chaturvedi HK, Phukan RK, Mahanta J. Sociocultural diversity and substance use pattern in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Girish N, Subbukrishna DK. Final report of the pilot study establishing health behaviour surveillance in respect of mental health. Report submitted to Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and WHO India Country Office, New Delhi. 2004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Gururaj G, Girish N, Benegal V, Chandra V, Pandav R. Burden and Socioeconomic impact of alcohol, The Bangalore Study, World Health Organization, South East Asia Regional office, New Delhi. 2006 [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Chavan B, Arun P, Bhargava R, Singh GP. Prevalence of alcohol and drug dependence in rural and slum population of Chandigarh: A community survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:44–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31517. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Reddy MV, Chandrashekhar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. John A, Barman A, Bal D, Chandy G, Samuel J, Thokchom M, et al. Hazardous alcohol use in rural southern India: Nature, prevalence and risk factors. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:123–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Sampath SK, Chand PK, Murthy P. Problem drinking among male inpatients in a rural general hospital. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:93. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Ray R. The Extent, Pattern and Trends Of Drug Abuse In India, National Survey, Ministry Of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government Of India and United Nations Office On Drugs and Crime, Regional Office For South Asia. 2004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. National Family Health Survey India-3. Available from: http://www.nfhsindia.org/nfhs3.html [Accessed on 2009 20 December]

- 31. Kumar MS. Rapid Assessment Survey of Drug Abuse in India. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. New Delhi, India. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/india/ras.html [cited in 2002]

- 32. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Rapid Situation and Response Assessment of drugs and HIV in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Srilanka: A regional report. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/pdf/india/26th_june/RSRA%20Report%20(24-06-08).pdf [Accessed on 2009 20 December]

- 33. United Nations office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2009. Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2009/WDR2009_eng_web.pdf [Accessed on 2009 20 December]

- 34. Benegal V. India: Alcohol and public health. Addiction. 2005;100:1051–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01176.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Nayak RB, Murthy P. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:977–83. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Murthy P, editor. Women and drug use in India. Substance, women and high risk assessment study: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India and United Nations Development Fund for Women. 2008 [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Kumar MS, Sharma M. Women and substance use in India and Bangladesh. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1062–77. doi: 10.1080/10826080801918189. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Ponnudurai R, Somasundaram O, Indira TP, Gunasekar P. Alcohol and drug abuse among internees. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:128–32. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Seshadri S. Substance abuse among medical students and doctors: A call for action. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:57–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Bhan A. Substance abuse among medical professionals: A way of coping with job dissatisfaction and adverse work environments? Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:308–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Sinha DN, Reddy KS, Rahman K, Warren CW, Jones NR, Asma S. Linking Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control: The case for India. Indian J Public Health. 2006;50:76–89. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Dhawan A, Jain R, Kumar N. Proceedings of the workshop on “Assessment of Role of Tobacco as a Gateway Substance and Information available on Evidence relating to tobacco, alcohol and other forms of substance abuse. All India Institute of Medical Sciences and World Health Organization, New Delhi. 2004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Bansal RK, Banerjee S. Substance use by child labourers. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:159–61. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Tripathi BM, Lal R. Substance abuse in children and adolescents. Indian J Pediatrics. 1999;66:569–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02727172. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Praharaj, Kumar S, Verma P, Arora M. Inhalant abuse (typewriter correction fluid) in street children. J Addict Med. 2008;2:175–7. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31817be5bc. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Benegal V, Sathyaprakash M, Nagaraja D. Alcohol misuse in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Report on project commissioned by the Indian Council of Medical Research and funded by Action Aid, India. 2008 [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Gupta R, Narang RL, Gupta KR, Singh S. Drug abuse among rickshaw pullers in industrial town of Ludhiana. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:145–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Dutta S, Kar N, Thirthalli J, Nair S. Prevalence and risk factors of psychiatric disorders in an industrial population in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:103–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33256. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Satija DC, Khatri JS, Satija YK, Nathawat SS. A study of prevalence and patterns of drug abuse in industrial workers. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1997;13:47–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Selvaraj V, Prasad S, Ashok MV, Appayya MP. Women alcoholics: Are they different from men alcoholics? Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:288–93. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Abraham J, Chandrasekaran R, Chitralekha V. A prospective study of treatment outcome in alcohol dependence from a deaddiction centre in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:18–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Babu RS, Sengupta SN. A study of problem drinkers in a general hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:13–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Vohra AK, Yadav BS, Khurana H. A study of psychiatric comorbidity in alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:247–50. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Gupta AK, Jha BK, Devi S. Heroin addiction: Experiences from general psychiatry out patients department. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:81–3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Sharma AK, Sahai M. Pattern of drug use in Indian heroin addicts. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:341–4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Samantary PK, Ray R, Chandiramani K. Predictors of inpatient treatment completion of subjects with heroin dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:282–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Saluja BS, Grover S, Irpati AS, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Drug dependence in adolescents 1978-2003: A clinical-based observation from North India. Indian J Pedatr. 2007;74:455–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0077-z. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Grover S, Irpati AS, Saluja BS, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Substance-dependent women attending a de-addiction center in North India: Socio-demographic and clinical profile. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59:283–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Narang RL, Gupta R, Mishra BP, Mahajan R. Temperamental characteristics and psychopathology among children of alcoholics. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:226–31. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Subodh BN, Murthy P, Chand PK, Arun K, Bala SN, Benegal V, Madhusudhan S. A case of poppy tea dependence in an octogenarian lady. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(2):216–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00134.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Gururaj G. Alcohol and road traffic injuries in South Asia: Challenges for prevention. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:713–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Benegal V, Gururaj G, Murthy P. Project Report on a WHO multicentre collaborative project on establishing and monitoring alcohol’s involvement in casualties: 2000-2001. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/Deaddiction [last cited in 2002]

- 63. Bhalla A, Dutta S, Chakrabarti A. A profile of substance abusers using the emergency services in a tertiary care hospital in Sikkim. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:243–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31556. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Reddy KS, Gupta PC, editors. Report on Tobacco Control in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi: Government of India; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Murthy P. Tilak Venkoba Rao Oration Alcohol dependence: Biological and clinical correlates. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:15–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Subodh BN, Benegal V, Murthy P, Girish NR, Gururaj G. Drug Abuse: News-n-Views. 2008. Alcohol related harm in India - an overview; pp. 3–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Grover S, Basu D. Cannabis and psychopathology: Update 2004. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:299–309. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Solomon SS, Celentano DD, Srikrishnan AK, Vasudevan CK, Anand S, Kumar MS, et al. Mortality among injection drug users in Chennai, India (2005-2008) AIDS. 2009;23:997–1004. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a594e. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Chandra PS, Carey MP, Carey KB, Prasada Rao PS, Jairam KR, Thomas T. HIV risk behaviour among psychiatric inpatients: Results from a hospital-wide screening study in southern India. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:532–8. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869147. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Panda S, Kumar MS, Lokabiraman S, Jayashree K, Satagopan MC, Solomon S, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection in injection drug users and evidence for onward transmission of HIV to their sexual partners in Chennai, India. J Acquir Immune Defic SynDr. 2005;39:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000160713.94203.9b. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Srinivasan K, Augustine MK. A Study of alcohol related physical diseases in general hospital patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:247–52. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Chowdhury AN, Sen P. Initiation of heroin abuse: The role of peers. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:34–5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Mattoo SK, Basu D, Malhotra A, Malhotra R. Relapse precipitants, life events and dysfunction in alcohol and opioid dependent men. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:39–44. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Mattoo SK, Basu D. Clinical course of alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:294–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Manjunatha N, Sahoo S, Sinha BN, Khess CR, Isaac MK. Chronology of alcohol dependence: Implications in prevention. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:233–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.42375. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Dhawan A, Kumar R, Seema Y, Tripathi BM. The Enigma of craving. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:138–43. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Saldanha D, Goel DS. Alcohol and the Soldier. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:351–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Chaudhury S, Das SK, Ukil B. Psychological assessment of alcoholism in males. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:114–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31602. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Saraswat N, Ranjan S, Ram D. Set-shifting and selective attentional impairment in alcoholism and its relation with drinking variables. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:47–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31619. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. SiriGowri DR, Suman LN, Rao SL, Murthy P. A study of executive functions in alcohol dependent individuals: Association of age, education and duration of drinking. Indian J Clin Psychology. 2008;35:14–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Sabhesan S, Natarajan M. Alcohol abuse and recovery after head Injury. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:143–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. Sabhesan S, Arumugham R, Natarajan M. Clinical indices of head injury and memory impairment. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:260–4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 83. Agarwal AK, Sethi BB, Gupta SC. Physical and cognitive effects of chronic bhang (cannabis) intake. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:1–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- 84. Sethi BB, Trivedi JK, Singh H. Long term effects of cannabis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:224–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 85. Rao AV, Chinnian RR, Pradeep D, Rajagopal P. Cannabis (Ganja) and cognition. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:233–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Venkoba Rao A, Ramachandran C, Parvathi Devi S, Hariharasubramanian N, Rawlin Chinnian R, Pradeep D, Rajagopal P, et al. Ganja and muscle. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:223–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Kumar R, Dhawan A. Reasons for transition and reverse transition in patients of heroin dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:19–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Basu D, Nitin G, Narendra S, Mattoo SK, Parmanand K. Endorsement and concordance of ICD-10 versus DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence: Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:378–86. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 89. Ray R, Neeliyara T. Alcoholism-diagnostic criteria and variability. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:247–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Ray R, Chandrasekhar K. Detection of alcoholism among psychiatric inpatients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:389–93. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 91. Manikant S, Tripathi BM, Chavan BS. Utility Of CIWA - a in alcohol withdrawal assessment. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:347–50. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 92. Chaudhury S, Das SK, Mishra BS, Ukil B, Bhardwaj P, Dinker NL. Physiological assessment of male alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:144–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 93. Ray R, Subash MN, Subbakrishna DK, Desai NG, SJ S, Ralte J. Male alcoholism-biochemical diagnosis and effect of abstinence. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:339–43. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 94. Mathrubootham N, Hariharan G, Ramakrishnan AN, Muthukrishanan V. Comparison of questionnaires and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinkers and alcoholics. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:42–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 95. Shankar SK, Ray R, Desai NG, Gentiana M, Shetty KT, Subbakrishna DK. Alcoholic liver disease in a psychiatric hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:35–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 96. Mattoo SK, Basu D, Malhotra A, Malhotra R. Motivation for addiction treatment-Hindi scale: Development and factor structure. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:131–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 97. Neeliyara T, Nagalakshmi SV. Development of motivation scale - clinical validation with alcohol dependents. Indian J Psychiatry. 1994;36:79–84. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 98. Janakiramaiah N, Venkatesha PJ, Raghu TM, Subbakrishna DK, Gangadhar BN, Murthy P. Brief addiction rating scale (Bars) for alchoholics: Description and reliabilty. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:222–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 99. Devadasan K. The effect of smoking on certain clinical diagnostic tests. Indian J Psychiatry. 1976;18:151–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 100. Varma S, Sengupta S. Type A- Type B clustering of alcoholics - A preliminary report from an Indian Hopsital. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:363–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 101. De B, Surendra K, Basu D. Age at onset typology in opioid dependent men: An exploratory study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:150–60. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 102. Gupta N, Basu D. The ongoing quest for sub-typing substance abuse: Current status. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:289–99. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 103. Jhingan HP, Jain R, Desai NG, Vaswani M, Tripathi BM, Pandey RM. Validity of self-report of recent opiate use in treatment setting. Indian J Med Sci. 2002;56:495–500. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 104. Sarkar J, Murthy P, Singh SP. Psychiatric co-morbidity of cannabis abuse. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:182–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 105. Goel D, Netto D. Cannabis: The habit and psychosis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:238–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- 106. Kulhalli V, Isaac M, Murthy P. Cannabis-related psychosis: Presentation and effect of abstinence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:256–61. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37665. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 107. Kisore P, Lal N, Trivedi JK, Dalal PK, Aga VM. A study of comorbidity in psychoactive substance dependence patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1994;36:133–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 108. Singh NH, Sharma SG, Pasweth AM. Psychiatric co-morbidity among alcohol dependants. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:222–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.43058. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 109. Basu D, Raj L, Mattoo SK, Malhotra A, Varma VK. The agoraphobic alcoholic: Report of two cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:185–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 110. Khalid A, Kunwar AR, Rajbhandari KC, Sharma VD, Regmi SK. A study of prevalence and comorbidity of depression in alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:434–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 111. Sringeri SK, Rajkumar RP, Muralidharan K, Chandrashekar CR, Benegal V. The association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and early-onset alcohol dependence: A retrospective study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:262–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44748. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 112. Murthy P, Taly AB, Jayakumar S. Seizures in alcohol dependence. German J Psychiatry. 2007;10:54–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- 113. Parkar SR, Seethalakshmi R, Adarkar S, Kharawala S. Is this ‘complicated’ opioid withdrawal? Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:121–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31604. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 114. Mattoo SK, Singh SM, Bhardwaj R, Kumar S, Basu D, Kulhara P. Prevalence and correlates of epileptic seizure in substance-abusing subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:580–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01980.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 115. Srinivasan TN, Suresh TR, Devar JV, Jayaram V. Alcoholism and psoriasis-an immunological relationship. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:302–4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 116. Arackal BS, Benegal V. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in male subjects with alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:109–12. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33257. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 117. Sampath G, Kumar YV, Channabasavanna SM, Keshavan MS. Alcoholic hallucinosis and paranoid schizophrenia-A comparative (clinical and follow up) study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:338–42. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 118. Satija DC, Sharma DK, Gaur A, Nathawat SS. Prognostic significance of psychopathology in the abstinence from opiate addiction. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:157–62. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 119. Pal H, Rajesh K, Shashi B, Neeraj B. Psychiatric co-morbidity associated with pheniramine abuse and dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:60–2. [ Google Scholar ]

- 120. Goswami S, Singh G, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Courses of substance use and schizophrenia in the dual-diagnosis patients: Is there a relationship? Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:338–46. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 121. Aich TK, Sinha VK, Khess CR, Singh S. Demographic and clinical correlates of substance abuse comorbidity in schizophrenia. 2004;46:135–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 122. Aich TK, Sinha VK, Khess CR, Singh S. Substance abuse co-morbidity in schizophrenia: An inpatient study of course and outcome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:33–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 123. Thirthalli J, Venkatesh BK, Gangadhar BN. Psychoses and illicit drug use: Need for cross-cultural studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01209.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 124. Isaac M, Chand P, Murthy P. Schizophrenia outcome measures in the wider international community. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;191:s71–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.50.s71. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 125. Basu D, Gupta N. Management of dual diagnosis patients: Consensus, controversies and considerations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:34–47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 126. Bhowmick P, Tripathi BM, Jhingan HP, Pandey RM. Social support, coping resources and codependence in spouses of individuals with alcohol and drug dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:219–24. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 127. Rao TSS, Kuruvilla K. A study on the coping behaviours of wives of alcoholics. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:359–65. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 128. Rao TSS, Kuruvilla K. A Study on the personality characteristics of wives of alcoholics. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:180–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 129. Ponnudurai R, Uma TS, Rajarathinam S, Krishnan VS. Determinants of sucidial attempts of wives of substance abusers. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:230–4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 130. Andrade C, Sarmah PL, Channabasavanna SM. Psychological well-being and morbidity in parents of narcotic-dependent males. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:122–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 131. Gupta S, Kulhara P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence: An overview and update. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:85–90. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33253. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 132. Muthy P, Guru SC, Channabasavanna SM, Subbakrishna DK, Shetty KT. Erythocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase - a potential marker for alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:38–42. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 133. Bhaskar LV, Thangaraj K, Osier M, Reddy AG, Rao AP, Singh L, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the ALDH2 gene in six Indian populations. Ann Hum Biol. 2007;34:607–19. doi: 10.1080/03014460701581419. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 134. Vaswani M, Prasad P, Kapur S. Association of ADH1B and ALDH2 gene polymorphisms with alcohol dependence: A pilot study from India. Hum Genomics. 2009;3:213–20. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-3-213. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 135. Deb I, Chakraborty J, Gangopadhyay PK, Choudhury SR, Das S. Single‑nucleotide polymorphism (A118G) in exon 1 of OPRM1 gene causes alteration in downstream signaling by mu-opioid receptor and may contribute to the genetic risk for addiction. J Neurochem. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06472.x. [Epub ahead of print] [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 136. Sringeri SK, Rajkumar RP, Muralidharan K, Chandrashekar CR, Benegal V. The association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and early-onset alcohol dependence: A retrospective study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:262–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44748. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 137. Benegal V, Venkatasubramanian GV, Antony G, Jaykumar PN. Differences in brain morphology between subjects at high and low risk for alcoholism. Addict Biol. 2006;12:122–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00043.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 138. Venkatasubramanian G, Anthony G, Reddy US, Reddy VV, Jayakumar PN, Benegal V. Corpus callosum abnormalities associated with greater externalizing behaviors in subjects at high risk for alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2007;156:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 139. Muralidharan K, Venkatasubramanian G, Pal P, Benegal V. Transcallosal conduction abnormalities in alcohol-naïve male offspring of alcoholics. Addict Med Addict Biol. 2008;13:373–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00093.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 140. Silva MC, Benegal V, Devi M, Mukundan CR. Cognitive deficits in children of alcoholics: At risk before the first sip! Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:182–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37319. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 141. Benegal V, Nayak M, Murthy P, Chandra P, Gururaj G. In: Women and alcohol in India. In Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspectives from Low and Middle Income Countries. Obot IS, Room R, editors. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- 142. Singh SM, Basu D. The P300 event-related potential and its possible role as an endophenotype for studying substance use disorders: A review. Addict Biol. 2009;14:298–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00124.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 143. Jagadeesh AN, Prabhu VR, Chaturvedi S K, Mukundan CR, Benegal V. Differential EEG response to ethanol across subtypes of alcoholics. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:S45. [ Google Scholar ]

- 144. Grover S, Bhateja G, Basu D. Pharmacoprophylaxis of alcohol dependence: Review and update part I: Pharmacology. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:19–25. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31514. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 145. Grover S, Basu D, Bhateja G. Pharmacoprophylaxis of alcohol dependence: Review and update part II: Efficacy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:26–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31515. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 146. Murali T, Rao IV, Keshavan MS, Narayanan HS. Thiamine refractory- wernicke-korsakoffs syndrome-a case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 1983;25:80–1. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 147. Mohan KS, Pradhan N, Channabasavanna SM. A report of subclinical psychological deterioration (A type of alcoholic dementia) Indian J Psychiatry. 1983;25:243–5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 148. Kumar CN, Andrade C, Murthy P. A randomized, double-blind comparison of lorazepam and chlordiazepoxide in patients with uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:467–74. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.467. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 149. Chand PK, Murthy P. Megadose lorazepam dependence. Addiction. 2003;98:1635–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00559.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 150. De Sousa AA, De Sousa J, Kapoor H. An open randomized trial comparing disulfiram and topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:460–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 151. Sousa AD, Sousa AD. A one-year pragmatic trial of naltrexone vs disulfiram in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:528–31. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh104. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 152. Sousa AD, Sousa AD. An open randomized study comparing disulfiram and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:545–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 153. Basu D, Jhirwal OP, Mattoo SK. Clinical characterization of use of acamprosate and naltrexone: Data from an addiction center in India. Am J Addict. 2005;14:381–95. doi: 10.1080/10550490591006933. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 154. Galgali RB, Srinivasan K, Souza GD. Study of spirometry and airway reactivity in patients on disulfiram for treatment of alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:273. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 155. Gangadhar BN, Subramanya H, Venkatesh H, Channabasavanna SM. Clonidine in Opiate detoxification. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:387–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 156. Subramanya, Channabasavanna SM. Clonidine in opiate withdrawal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:375–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 157. Satija DC, Natani GD, Purohit DR, Gaur R, Bhati GS. A double blind compartive study of usefulness of clonidine and symptomatic therapy in opiate detoxification. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:55–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 158. Nigam AK, Ray R, Tripathi BM. Non completers of opiate detoxification programme. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:376–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 159. Rao RV, Dhawan A, Sapra N. Opioid maintenance therapy with slow release oral morphine: Experience from India. J Substance Use. 2005;10:259–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 160. Muralidharan K, Rajkumar RP, Mulla U, Nayak RB, Benegal V. Baclofen in the management of inhalant withdrawal: A case series. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:48–51. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0108. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 161. Chandiramani K, Tripathi BM. Psycho - educational group therapy for alcohol and drug dependence recovery. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:169–72. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 162. Kumar PS, Thomas B. Family intervention therapy in alcohol dependence syndrome: One-year follow-up study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:200–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37322. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 163. Murthy P, editor. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Govt of India, United Nations Drug Control Program, International Labour Organization. European Commission publication; 2002. Principal author and Scientific Editor. Partnerships for Drug Demand Reduction in India. [ Google Scholar ]

- 164. Chandrasekaran R, Sivaprakash B, Chitraleka V. Five years of alcohol de-addiction services in a tertiary care general hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:58–60. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 165. Prasad S, Murthy P, Subbakrishna DK, Gopinath PS. Treatment setting and follow up in alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:387–92. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 166. Murthy P, Chand P, Harish MG, Thennarasu K, Prathima S, Karappuchamy, et al. Outcome of alcohol dependence: The role of continued care. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:148–51. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.51226. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 167. Kar N, Sengupta S, Sharma P, Rao G. Predictors of outcome following alcohol deaddiction treatment: Prospective longitudinal study for one year. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:174–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 168. Ranganathan S. Conversation with Shanthi Ranganathan. Addiction. 2005;100:1578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01197.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 169. Varma VK, Singh A, Malhotra AK, Das K, Singh S. Popular attitudes towards alcohol, use and alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:343–50. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 170. Mohan D, Adityanjee, Saxena S, Sethi HS. Drug and alcohol dependence: The past decade and future, view from a development country. Indian J Psychiatry. 1983;25:269–74. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 171. Mahal A. What works in alcohol policy? Evidence from rural India, Economic and Political weekly. 2000 [ Google Scholar ]

- 172. Ramachandran V. The prevention of alcohol related problems. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:3–10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 173. Benegal V, Chand PK, Obot IS. Packages of care for alcohol use disorders in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000170. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 174. Armed Forces Medical College. Standard treatment guidelines and costing. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/en/Section2/Section428_1503.htm 26 Nov 2007.

- 175. Varma VK, Malhotra AK. Management of alcohol related problems in general practice in north India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:211–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 176. Malhotra A, Mohan A. National policies to meet the challenge of substance abuse: Programmes and implementation. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:370–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 177. Ray R. Substance Abuse and the growth of de-addiction centres: The challenge of our times. In: Agarwal SP, editor. Mental Health: An Indian Perspective 1946-2003. Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. New Delhi: 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- 178. Benegal V, Bajpai A, Basu D, Bohra N, Chatterji S, Galgali RB, et al. Proposal to the Indian Psychiatric Society for adopting a specialty section on addiction medicine (alcohol and other substance abuse) Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:277–82. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37669. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

COMMENTS

The Shodhganga@INFLIBNET Centre provides a platform for research students to deposit their Ph.D. theses and make it available to the entire scholarly community in open access. The repository has the ability to capture, index, store, disseminate and preserve ETDs submitted by the researchers.

This paper examines the nature of job polarisation in India during the period 1983-2012 when Indian manufacturing sector was being automated. The research uses disaggregated data from National Sample Survey Office and examines the impact of supply-side factors such as nature of employment and presence of educated labour force.

Policy Research Working Paper 6714. This paper offers a comprehensive analysis of poverty in India. It shows that no matter which of the two official . poverty lines is used, poverty has declined steadily in all states and for all social and religious groups. Accelerated growth between fiscal years 2004-2005 and 2009-2010

Different States of India: An Empirical Analysis Priyadarshi Dash & Rahul Ranjan RIS-DP # 286 November 2023 Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 110 003 (India) Tel: +91-11-2468 2177/2180; Fax: +91-11-2468 2173/74 Email: [email protected] RIS Discussion Papers intend to disseminate preliminary findings of ...

paper develops argument on the basis of secondary sources as review of existing literature published in journal, books, reports of various, NGOs, Government and international organisations and websites. The paper critically examines women empowerment in India, various models and dimensions.

International Journal of Advanced Research in Commerce, Management &Social Science (IJARCMSS) 129 ISSN :2581-7930, Impact Factor : 6.809, Volume 05, No. 04(II), October-December, 2022,pp 129-134 ... The current paper purpose to interpret the element leading to unemployment and its impact on the Indian ... • India unemployment rate for 2022 ...

Mental asylums were established in India during the colonial era, primarily under British rule. The first mental asylum in India, the Indian Lunatic Asylum, was established in 1745 in Calcutta (now Kolkata). These institutions were initially established to confine and segregate individuals with mental illness from the rest of society.

1 Both China and Vietnam have consistently invested much more on health and education than India. In 1980, India's adult (15+) literacy rate was just 41% compared to 65% in China and 84% in Vietnam; in 2010, India's expenditure on health was 1.2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) compared to 2.7% in China (Dr`eze and Sen ,2013). 2

Brookings India Research Paper No. 072019. The Brookings Institution India Center serves as a platform for cutting-edge, independent, policy-relevant research and analysis on the opportunities and ...

Keywords: Alcohol, drugs, India, research, substance use. INTRODUCTION. ... An area with enormous implications for public health, it has generated a substantial amount of research. In this paper we examine research in India in substance use and related disorders. Substance use includes the use of licit substances such as alcohol, tobacco ...