50+ Clinical Trials with Compensation Near You

Home / Clinical Trials / 50+ Clinical Trials with Compensation Near You

Clinical trials with compensation are a great opportunity to get involved in important medical research. A clinical trial is held to gather data on the potential of a novel treatment to address a specific illness. A clinical trial often focuses on people with a certain chronic condition or genetic risk factors.

A clinical study with compensation focuses on paying individual for participating in their trials. This helps study teams to more quickly drive interest around a trial, and also helps to ensure that clinical trial participants subsist through the entire trial. Some clinical trials with compensation also recruit healthy volunteers, those with no specific diagnosis or special medical needs. Which volunteers are needed for which study depends on the study’s goals. Nobody qualifies for every study, but through effective upfront communication with the study team most participants can quickly learn whether or not they are a good fit for an observational study or investigational treatment.

Compensation for research studies is a hot topic for both participants and organizers. Not all clinical trials with compensation fit everyone, but the right trial can help participants defray their costs and earn some money – anywhere from just $10 for a single visit to multiple thousands for longer studies.

Each clinical trial responds to diverse needs, so there’s no way of knowing precisely how much any given study will offer in compensation. With that said, there are a few basic facts you should know as you do research and decide whether participating in a trial focused on an investigational drug or treatment plan is the right fit for you.

Find Trials With Compensation

Register for trial updates, clinical trials for healthy volunteers with compensation, how much can volunteers make in clinical trials with compensation.

Compensation for clinical trials varies widely. It can range anywhere from below $100 to thousands of dollars for qualified participants. Compensation generally scales with the length and complexity of the trial, with individuals participating in the entire study maximizing their compensation. The shorter a clinical research study, the lower the amount of compensation offered, just as with research studies in other fields.

Can You Get Expenses Paid for in a Clinical Trial?

When you are cleared to participate in a research study, you will usually have any direct costs related to the study covered by the presiding company or organization. For example, you will not need to pay for a treatment given to you as part of a research study, and it does not matter if you have insurance.

Depending on the structure of the study, you may or may not qualify to have certain indirect expenses paid for. The most common indirect expense is travel. If you need to travel a long way from your home to a laboratory facility, you can often submit receipts for gas or other expenses for reimbursement.

When Do You Receive Clinical Trial Compensation?

Reimbursements are generally processed soon after they are received. On the other hand, if you’ve been offered a flat sum for your participation in the study, you will usually only receive it at a certain point in the study or after specific conditions are met.

These “conditions” usually relate to the length of the study. For example, a study that’s intended to run for a year might compensate volunteers every three months. This recognizes the fact that even some of the volunteers who qualify will not necessarily stay with the study for its entire duration.

Which Clinical Trials Offer the Most Study Compensation?

There’s no way of knowing exactly how much any given trial will provide in compensation until you contact the study sponsor. In order to make sure that you are a good fit for the trial, there will be a thorough screening process that makes sure you are a good fit, pass the exclusion criteria, and will complete the trial. As a general guideline, though, more complex clinical trials provide more compensation.

Many clinical trials have only a few basic requirements. As long as you meet the exclusion criteria, all you need to do is take the medical treatments as directed and occasionally get blood tests or other laboratory tests. But sometimes, researchers will need more information from you or will be in contact more frequently with the study physician or research team.

For instance, you might be asked to maintain a “clinical trial diary” that gives greater insight into how a condition responds at different times after treatment. This is an example of something the study research staff might figure into their calculations when determining compensation.

Is Compensation for Clinical Trial Participation Based on the Study’s Outcome?

In a word, no. A clinical trial will not offer its volunteers more or less money based on whether or not the research was successful, but rather fully participating in studies should aware you with the full compensation package. In fact, it might be months or even years before anyone can say with full certainty whether a study had the results the sponsor hoped for.

While you’re never responsible for the outcome of a study, your level of participation is definitely a factor. If you accidentally fail to follow instructions (on treatment dosage or timing, for example) it potentially invalidates your data, which may preclude compensation.

How Do I Find Out How Much Compensation a Trial Offers?

Most clinical trials with compensation advertise that compensation is available. However, a study sponsor might be legally limited in how much information they can publicize. Once it’s been verified that you match the required volunteer profile, you will receive written documentation of compensation and requirements. In some situations, an annual trial compensation package might be appropriate based on the types of interventions or medical treatments being tested.

Compensation for clinical trials makes it easier and more accessible to be a part of important medical research. Your decision to participate could help people all around the world that you will never meet, and help study drugs and treatment get out to market more quickly.

Are There Clinical Trials That Offer Compensation Near Me?

Most studies, especially ones that focus on healthy volunteers, have various locations and can even be ran in multiple countries. While technology is still being developed to allow participants to remotely participate in clinical trials, generally most study teams and study sponsors still require clinical trial participants to meet in-person based on the study design during the trial to check in on the progress of a treatment. Most major cities in the United States will offer some clinical trials that offer financial compensation and studies with locations near you.

Other Conditions

- Acute Aortic Dissection

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Alzheimer’s

- Auditory Loss and Deafness

- Autoimmune Hepatitis

- Bronchiectasis

- Breast Cancer

- Esophageal Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Ovarian Cancer

- Pancreatic Cancer

- Prostate Cancer

- Skin Cancer

- Compensation

- COPD Treatments

- Coronavirus

- Crohn’s Disease

- Diet And Nutrition

- Endometriosis

- Fibromyalgia

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Mindfulness

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Myasthenia Gravis

- Ophthalmology

- Osteoarthritis

- Parkinson’s Disease

- PBC and PSC

- Plant Based Diet

- Plastic Surgery

- Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Urinary Tract Infections

- Weight Loss

Trials With Compensation

Accepting Healthy Volunteers From Across the US.

Register for Updates

Receive notifications for trials that match your criteria.

Sign up to receive email notifications on clinical trials for individual conditions in your local area.

Tips for Compensating Research Participants

Researchers should consider the risk of coercion when developing a compensation plan to pay participants for human subjects research..

Compensation is a predetermined form of payment provided to research participants for their engagement in a research activity. Compensation can include travel reimbursement (e.g., a preloaded METROcard), electronic gift cards, and cash. A small compensation as an incentive for completion of a study is permitted so long as such incentive is not coercive. Teachers College Institutional Review Board (IRB) does not consider compensation a benefit.

Distribution of compensation may also include other departments (e.g., accounts payable) besides the IRB office. Researchers should consult the appropriate sources to determine the best way to distribute payment to study participants.

This article will cover the following topics related to participant compensation:

- How to disclose your plan to compensate participants for their involvement in a research study.

- The potential for coercion and how to determine a fair compensation amount.

- Guidance specific to certain study populations.

Disclosing a Plan to Compensate Participants

An IRB protocol submission is composed of the IRB Application Template and any documentation relevant to the study, such as consent documents, recruitment materials , or site permission forms (e.g., Informed Consent Form Template , Site Permission Template ). In the IRB application and on consent forms, researchers should detail their plans to compensate participants. The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) recommends researchers include “a detailed account of the terms of payment, including a description of the conditions under which a subject would receive partial or no payment (e.g., what will happen if he or she withdraws part way through the research or the investigator removes a subject from the study for medical or noncompliance reasons),” and that “payment [may] be prorated for the time of participation in the study rather than delayed until study completion because the latter could unduly influence a subject’s decision to exercise his or her right to withdraw at any time” ( HHS.gov, Attachment A ).

A compensation plan should include…

- An explanation of how participants will be compensated.

- (e.g., “Compensation will be prorated for completion of each study activity”).

- The amount and form of compensation.

- (e.g., $25 Amazon gift card, $30 cash, $10 preloaded METROcard, etc.).

- How the researcher will distribute the compensation to participants, including any identifiable information that may be collected during the process.

- (e.g., “Participants will be given the option to enter their email address at the end of the survey if they would like to receive compensation. Upon successful completion of the survey, the researcher will send a $25 Amazon gift card to the participant’s email. Participants’ contact information and survey data will be stored separately and their personally identifiable information will not be published or presented publicly.”)

- Circumstances under which participants may or may not be compensated.

- (e.g., “You may leave the interview at any time. Participants who complete 75% of the survey questions or more will receive a $20 gift card.” Alternatively, “You may leave the study at any time. All eligible participants, regardless of whether they leave the study early, will receive a $10 preloaded METROcard.”) .

- For studies that extend over the course of several sessions or days, consider prorating the compensation.

- (e.g., “You will complete three one-hour interviews over the course of 6 months. After each interview, you will receive a $20 gift card. After completing all three interviews, you will be given an additional $10 gift card. Your total compensation for this study is up to $70.”)

Potential for Coercion

“Influence is contextual, and undue influence is likely to depend on an individual’s situation” (HHS.gov, Attachment A ). Federal guidelines rarely provide precise standards for determining undue influence. As a result, TC IRB reviews each protocol submission on a case-by-case basis. Based on provisions set by the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) , IRBs make reasonable assessments “to minimize the likelihood of undue influence or coercion occurring. For example, IRBs may restrict levels of financial or nonfinancial incentives for participation and should carefully review the information to be disclosed to potential subjects to ensure that the incentives and how they will be provided are clearly described. Known benefits should be stated accurately but not exaggerated, and potential or uncertain benefits should be stated as such, with clear language indicating how much is known about the uncertainty or likelihood of these potential benefits” (HHS.gov, Attachment A ).

When determining whether compensation is coercive or causes undue influence, the IRB will weigh the participant qualifications against the intensity of tasks and time spent on study activities. Participant compensation is typically metered on average wages (salary based on profession) and time spent on tasks. Compensation that is more (or less) than this amount should be justified by the researcher.

The IRB will also consider how the researchers describe the compensation in their recruitment materials. In general, information about compensation should be secondary (in both content and formatting) to information about the study. Recruitment materials that format or highlight compensation as the main feature, or make compensation an inducement to participate in a study, are coercive and will be sent back to the researcher for revisions.

An acceptable recruitment flyer might read, “This study will examine the effects of sleep habits and sleep deprivation on the brain and body. You must be enrolled in a university program to be eligible to participate. This study is conducted by Dr. Anna Freud ( [email protected] ) at the Brain Lab, Teachers College, Columbia University (Protocol ID: 10-001). Participants will receive a physical exam and $100 for their participation.”

An unacceptable, or coercive, recruitment flyer might read, “Chance to get $100 and Free Medical Care just for talking about your Sleep Habits! Email [email protected] to get paid today!!”

Population Specific Guidances

The IRB will also consider whether the compensation is fitting for the population of interest. For example, youth should not be given monetary compensation. However, small gifts such as pens or erasers may be fitting for a short, school-based study.

New York City’s law states that NYC Department of Education teachers cannot receive compensation for participation in research studies . This means that TC researchers cannot give teachers monetary compensation for research conducted during class time or typical work hours. Researchers who would like to offer teachers compensation should conduct the study during the teachers’ personal time. Alternatively, if your research activities must fall during class time, consider providing teachers with non-monetary compensation (such as school supplies) or donations. For all studies, the IRB will make a decision on a case-by-case basis.

For more information on coercion and risk to participants, please review our guide to Understanding Potential Risks for Human Subjects Research . If you have specific questions about compensating participants, please contact the IRB at [email protected].

- NYC DOE IRB Information for Principals

- OHRP's Attachment A

- AMA Journal of Ethics: When Does the Amount We Pay Participants Become "Undue Influence"?

— Kailee Kodama Muscente, M.A.

Tags: Recruitment Consent New to IRB

Published Tuesday, Jul 6, 2021

Institutional Review Board

Address: Russell Hall, Room 13

* Phone: 212-678-4105 * Email: [email protected]

Appointments are available by request . Make sure to have your IRB protocol number (e.g., 19-011) available. If you are unable to access any of the downloadable resources, please contact OASID via email [email protected] .

Division of Research

Compensation for research participants.

- The Research Cycle

- Conduct Research

- Human Subjects Research at Brown

- HRPP/IRB Policies and Guidance

- Recruiting Research Participants

Compensating research participants is a way to thank them for contributing their time and recognize their willingness to take on some of the research-related risks of study activities. As compensation is an expression of gratitude by researchers for their participants, it is not a benefit of participation, and it must be fair and equitable. However, offering compensation is not required or expected.

Review of Compensation Plan

Brown’s Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) team, along with the Institutional Review Board (IRB), reviews and determines whether compensation is reasonable and if it unduly influences participation. All information concerning compensation — including the method, amount and schedule of payment — should be clearly stated when submitting study materials for HRPP/IRB review.

The HRPP team and IRB will take into account information from the community and culture as it evaluates the appropriateness of participant compensation.

Consent Forms for Research Participants

Compensation and Taxes

All payments and gifts to research participants are considered income by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and may be reportable to the IRS as taxable income. You are responsible for informing participants during the consent process that the payment they receive is taxable income and may be reportable to the IRS.

If a participant receives $600 or more from one or across a combination of research studies at Brown University within one calendar year, they will be taxed on this income. You are required to provide to Accounts Payable a participant’s legal name, address, Social Security number and the amount paid for participation. Brown uses this information to issue 1099 statements to study participants.

Accounts Payable Office

Reimbursement vs. Compensation

Reimbursement is not compensation for research participation. You may reimburse research participants (or their caregivers) for out-of-pocket expenses they have as a result of study enrollment, such as transportation, childcare, meals and similar expenses. Reimbursement payments are not reportable to the IRS as taxable income.

Offering reimbursement is not required or expected.

Compensation Methods at Brown

The Brown University’s Controller’s Office is responsible for ensuring the proper stewardship of the University’s financial resources. The HRPP team and IRB rely on the Controller’s Office to determine which forms of compensation comply with federal and state laws and University policy. Only these forms of compensation are available to investigators for human subjects research.

You are strongly encouraged to design your study using one of the compensation methods approved by the Controller’s Office, listed below. If you intend to use a method of compensation that is not approved, you will need to contact Accounts Payable for consultation and approval for its use before including the compensation in your study materials submitted for HRPP/IRB review.

Brown uses ClinCard to manage the reimbursement process for study participants. ClinCard is a participant payment system that makes it easier, faster and more secure to provide compensation to participants and to track payments through an online system. Studies that use the ClinCard as a means to provide monetary compensation to participants must include required language in the consent document and provide participants with IRB-approved FAQs about the system. Study staff may also be required to attend training on the use of the system.

If study participants wish to cash out their ClinCard balance at a bank teller, as a means to get cash without incurring a fee, it is recommended that they take a copy of the ClinCard Bank Instructions with them.

If you are interested in using the ClinCard in your study, please contact the Controller's Office. Additional guidance can be found on the office’s ClinCard page.

- Approved Language for ClinCard Consent

- ClinCard FAQs for Participants

- ClinCard Bank Instructions (PDF)

- Controller’s Office

- ClinCard Guidance

Cash and Gift Cards/Certificates

Cash payments and gift cards (plastic, paper or electronic) are common ways to compensate participants. Please review Brown’s Gift Card Policy for any requirements that may apply to your study.

Even if you will not collect identifying information about your participants, you should establish a way to track the cash payments and/or gift cards given to participants for reporting purposes to the Controller’s Office. For example, consider keeping a spreadsheet that links a unique identifying number from each gift card to an assigned study ID associated with a given participant.

Gift Card Policy

Unacceptable Compensation Methods

The Controller’s Office may determine that a compensation method does not meet Brown’s requirements for a number of reasons (i.e., it does not offer buyer or seller protection or there are no special authorizations, no offers of controls or reconciliation capability that would be acceptable to Brown or no ease of payments for the user). The determination of which compensation options are available for human subjects research is not a decision that is made by or can be overturned by either the HRPP team or the IRB.

If you would like to request that the Controller’s Office consider a method of compensation that is not already approved by Brown for use in human subjects research, please contact Accounts Payable at [email protected] or 401-863-2716.

At this time, the following compensation methods are specifically not allowed for human subjects research studies, as determined by the Controller’s Office:

- PayPal mobile payment service

- Venmo mobile payment service

Additional Guidance

Advertising compensation.

Your advertisement may state that participants will be compensated but should not emphasize the compensation by font (i.e., large or bold type) or design enhancements (i.e., exclamation marks, stars, subject/tag lines in electronic communications).

Prorated Compensation and Bonuses

Compensation for participation in research should not be contingent upon the participant completing the entire study but rather be prorated as the study progresses to insure voluntary participation. However, compensation of a small proportion as an incentive for completion of the study is acceptable providing that such an incentive does not constitute undue influence.

If a bonus is given at the completion of the study it should not be more than half of the total study compensation.

Sponsor Discounts

Compensation for participation in a clinical trial offered by a sponsor may not include a coupon good for a discount on the purchase price of the product once it has been approved for marketing.

- Whitepapers

- Ethics in Clinical Research

- Participant Recruitment

Compensating Participants in Clinical Research: Current Thinking

In clinical research studies, it is not uncommon for monetary compensation to be provided to research participants; as reimbursement for study-related expenses, as compensation for time and effort, and even as incentive payments to encourage enrollment. Sponsors, researchers and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) are often wary about payments in research participation, citing concerns about coercion and undue influence, whether real or perceived, and have avoided payments that are “too high.”

But new research on how people make decisions about research participation, and new approaches to this question, bring a new perspective; are payments to participants actually too low? This paper explores this question, and whether we should, in fact, worry much less about restricting compensation for research participants.

Undue Influence and Coercion

“…the IRB must conclude that participation in any protocol it approves is reasonable (i.e., not unreasonable) for individuals in the target study population. This is not to say that no risk remains or that participation in research would be in the best interest of potential participants. Neither is required in order to avoid undue influence.” 1

At the foundation of the concerns about research participant payment are the issues of undue influence and coercion. These words are not clearly defined in research regulations or guidance, and are often used interchangeably when talking about participant payment, but they actually have very different meanings.

To coerce means to achieve something by using force or threat. Situations of true coercion are rare in clinical study recruitment situations. An example of coercion might be a physician who is seeing a patient at a free clinic who says, “If you don’t agree to be in my research study, you can’t come here for care anymore.” Payment offers, though, are not force, nor are they threats. Therefore, offers of payment for participation in research can never be coercive.

Influence is a different concept. Influence, in itself, is not a bad thing. Everyone makes decisions about what they do based on factors that influence them, and sometimes those factors are financial. While many of us really enjoy our jobs, if our employer told us that we wouldn’t get paid anymore, we’d probably stop showing up for work. The issue, then, is not influence, but undue influence. In legal terms, undue influence means that someone makes someone else behave in a way that is contrary to their interests. In research, we often describe undue influence in study recruitment as someone agreeing to take risks that were not reasonable, because they were influenced by other considerations (in this situation, by the offer of money).

But as discussed in the excellent recent paper, Paying Research Participants: The Outsized Influence of “Undue Influence” by Emily Largent and Holly Fernandez Lynch 1 , the possibility of unreasonable risks requires more consideration as well. In order for an IRB to approve a research study, the Board must ensure that the risks of the research are reasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits, for the target study population. If this is the case, for a research protocol that has been IRB-approved and a potential participant who is in the target study population, how can the offer of payment influence them to take risks that are unreasonable, when the risks have already been determined to be reasonable? With this argument, Largent and Lynch explain that the potential problem of undue influence in IRB-approved research is significantly overestimated, although possible in some very specific situations (for example, when potential participants are likely to deceive the researchers about their eligibility or when they have some unique characteristics outside the IRB’s purview). In an effort to reduce the occurrence of these situations—although they are already rare—we as a research community have erred on the side of caution in preventing payment or encouraging payment to be kept relatively low. However, underpaying for participation results in the possible exploitation of research participants, the overburdening of certain populations who are willing to accept low payments, and the scientific risks of failed studies due to under-enrollment.1 For minimal risk research, any concern at all about compensation is likely unnecessary, as the risks are so low that it would be very unlikely that any participant could be making a decision to take a risk that is unreasonable.

Types of Payments to Participants

Reimbursement of study-related expenses.

Reimbursement of expenses related to participation in research studies, whether provided by the sponsor or by the institution, should never be of ethical concern. While there are rare instances in which ethically-acceptable studies involve requiring participants to pay for study-required procedures or medications—most often in situations where diagnostic testing is being used for both clinical and research purposes—for the most part, research participation should be cost-neutral. Making research cost-neutral helps to ensure the principle of distributive justice, and that the risks and benefits of research participation are fairly distributed. If each research visit involves out-of-pocket expenses for gas, food during a long wait between scheduled blood draws, parking fees, and child care, then only those who can afford those expenses would be able to participate in the research. Coverage of expenses for airfare, overnight hotel stays, and other long-distance travel for research participation used to prompt additional ethical concerns based on the higher amounts of money involved. Comfort for these practices has grown over the last several years, in part based on studies in rare diseases and more specific patient populations, where the research is conducted at centers of excellence but potential subjects may be coming from other states or even other countries.

A number of different models for covering out-of-pocket expenses are acceptable including collection of receipts and reimbursement in cash or check; vouchers for taxis, parking or meals; pre-funded debit cards; or providing a per-diem amount based on average and expected expenses. Comfort has also grown with using third party vendors such as Uber and Lyft to bring participants to study visits, with direct billing to the sponsor.

Compensation for Time and Effort

Studies which include compensation for the time and effort of research participants should make an effort to consider the actual time spent on the study, including study visits, tasks outside study visits (completing surveys or diaries), and even travel time to clinical sites, keeping in mind that participants may be missing work in order to complete the study requirements. Payment amounts should be high enough so that they do not take advantage of populations with lower income; proposed payment amounts are sometimes based on local minimum wages, which provides a handy benchmark, but basing study payment on a low wage does have the effect that anyone who makes more than that wage will be losing money if they miss work for study commitments.

There are a number of models that have been proposed for the compensation of research participants, including a wage-payment model, and payment based on market forces and supply and demand. 2

Incentive Payments

Some study plans include, either explicitly or implicitly, the payment to potential participants in a manner or at a rate that is intended to persuade them to participate in the research study, above what might be considered compensation for time or effort. For example, one study offered to pay the costs of elective plastic surgery for which the patients were already scheduled—several thousand dollars—if the patients agreed to participate in a 24-hour-long post-operative study comparing a new pain medication to the standard medication. Another study offered access to services (consultation with personal coaches) and gifts up to a value of approximately $6000 for participation in a study that required the completion of a survey every three months for a year. While the initial reaction to the amounts of money involved is usually caution, if we go back to the discussion of undue influence earlier in the paper, is there truly a valid concern? In both cases, an IRB had determined that the risks of the research were reasonable in relation to the potential benefits; in the second example, the risks were minimal. If the sponsor is willing to pay a certain amount of money to ensure that they were able to enroll the study with the necessary number of participants and in a reasonable amount of time, these types of payments should be acceptable.

Efforts to protect research participants from undue influence, and researchers and sponsors from perceptions of trying to use undue influence, have long been a major concern for IRBs. However, the true risk of undue influence is significantly lower than has often been assumed, when considering research that has been IRB-approved and for which the risks are considered to be reasonable. Instead, parties involved in research should consider whether payments to research participants are sometimes too low.

- Largent E and Lynch HF. Paying research participants: The outsized influence of “undue influence.” IRB: Ethics & Human Research 2017;39(4):1-9.

- Grady C. Payment of clinical research subjects. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(7):1681-1687. doi:10.1172/JCI25694.

Don't trust your study to just anyone.

WCG's IRB experts are standing by to handle your study with the utmost urgency and care. Contact us today to find out the WCG difference!

Event Details

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Study participants incentives, compensation and reimbursement in resource-constrained settings

Takafira mduluza, nicholas midzi, donold duruza, paul ndebele.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Selected articles from the 3rd Ethics, Human Rights and Medical Law Conference (3rd EHRML)

Sylvester Chima, Takafira Mduluza and Julius Kipkemboi

Publication of this supplement has been funded by the College of Health Sciences and the Research Office at the University of Kwazulu-Natal. Articles originate from the 3rd EHRML conference, which was organized by Informa Life Sciences Exhibitions. The articles have undergone the journal's standard peer review process for supplements. The Supplement Editors declare that they have no competing interests.

7-9 May 2013

3rd Ethics, Human Rights and Medical Law Conference, Africa Health Congress 2013

Johannesburg, South Africa

Collection date 2013.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Introduction

Controversies still exists within the research fraternity on the form and level of incentives, compensation and reimbursement to study participants in resource-constrained settings. While most research activities contribute significantly to advancement of mankind, little has been considered in rewarding directly the research participants from resource-constrained areas.

A study was conducted in Zimbabwe to investigate views and expectations of various stakeholders on study participation incentives, compensation and reimbursement issues. Data was collected using various methods including a survey of about 1,008 parents/guardians of school children participating in various immunological cohort studies and parasitology surveys. Community advisory boards (CABs) at 9 of the sites were also consulted. Further, information was gathered during discussions held at a basic research ethics training workshop. The workshop had 45 participants that including 40 seasoned Zimbabwean researchers and 5 international research collaborators.

About 90% (907) of the study participants and guardians expected compensation of reasonable value, in view of the researchers' value and comparison to other sites regardless of economic status of the community. During discussion with researchers at a basic ethics training workshop, about 80% (32) believed that decisions on level of compensation should be determined by the local research ethics committees. While, the few international research collaborators were of the opinion that compensation should be in accordance with local guidelines, and incentives should be in line with funding. Both the CAB members and study participants expressed that there should be a clear distinction between study incentive and compensation accorded to individual and community expectations on benefits from studies. However, CABs expressed that their suggestions on incentives and compensation are often moderated by the regulatory authorities who cite fear of unknown concerns.

Overall, both personal and community benefits need to be considered colectively in future studies to be conducted in resource-constrained communities. There is projected fear that recruitment in future may be a challenge, now that almost every community, has somehow been reached and participated in some form of studies. A major concern on reimbursement, compensation or incentives should be internationally pegged regardless of different economic status of the individuals or communities where the study is to be conducted.

Keywords: study participants, incentives, compensation, reimbursement, resource-constrained

Biomedical studies are well known to add scientific solutions to problems bedeviling mankind, animals and their environment [ 1 - 3 ]. Through conducting research activities, some benefits are also realized by individuals and communities worldwide. Research programs assist in finding out new ways for treatment, to solve some medical problems and to improve the health standards of living for humans [ 4 ]. However, with the benefits realized at multiple-levels, concern is raised where the subjects of the research activities, who are at the core of the programme, rarely obtain any visible individual benefits [ 5 ].

Research participants indulge in different study protocols for different reasons. Sometimes the main driving force is beyond the participants' control [ 6 ]. While currently, the international research foundations and organizations are struggling to rationalize participation, in an effort to tame the research jungle [ 7 , 8 ]. However, at individual levels there are a couple of questions that go unanswered for the participants who are right at the bottom of the planning and the research protocol hierarchy [ 5 , 6 ]. Some of the pertinent questions by the research participants that go unanswered include the following: i). What is my immediate benefit? ii). Who will benefit from this work being conducted? ii). Why are these people (researchers) using all the resources in my community and yet we have so many other problems? iii). Why my community and not that other community? iv). The researchers are here for only 2 years, then what next? v). These people are well off, better than anyone in our community, so they must be benefiting from the activities?

While researchers are well aware of the main goal(s) including on how to achieve these through data/sample gathering, a lot need to be understood on the study participants and their feelings. Further, it is reasonable not to assume but to become part of the community and feel from within what the participants expect from taking part in studies and providing their biological specimens. Some progress has been achieved along these lines with moderate consideration on certain aspects that affect study participants in the form of repayment or reimbursement, which is replacement of what could have been lost or what could have been gained during the time the participant is involved in the research activities [ 9 - 13 ]. While there are other forms that have been coined into studies that include giving out incentives; that represents something that motivates or encourages participation. Incentives are rarely permitted by study regulators for reason still unclear to many researchers, especially when an incentive is considered as payment or a concession to stimulate greater participation, this is regularly not permitted by most in-country study regulatory agents and in certain instances by research groups [ 5 ]. Where the commonly applied consideration of benefits to study participation by researchers is compensation, representing something that makes up for an undesirable or unwelcome state of affair or this can be something, typically money awarded to someone as a recompense for loss, injury or suffering.

Most research activities involve an intertwined relationship between different players working together to achieve a common goal. In the case of simple investigative research emanating from a researcher, there are several regulatory authorities that may be responsible for giving approval for sample shipping or exchange, drug use and other commonly regulated activities [ 14 ]. Additionally, there could be some local authorities that are responsible for over sight within certain areas and research institutions. Key to the regulatory and monitoring biomedical research involving humans is the ministry of health and other ministries that deal with the public. In certain locations, there is political leadership that has control over access and running any research activities in their communities [ 5 ]. The biomedical researcher/investigator has to prepare documents that go through all the required local regulatory institutions and offices that include the ethics review board. The ethics review committees are believed to be representing the communities where research is to be conducted. The members are believed or expected to have the community at heart and to also have in-depth understanding of both traditional and cultural beliefs. In this hierarchy, the research community/participants are located right at the bottom or the receiving end. The concerns of the community or participants are assumed as represented by the structures within the areas and the regulatory authorities [ 5 , 14 ].

Controverses exists on the forms and levels of incentive, compensation and to lesser extent re-imbursement to study participants in resource-constrained settings. Inequity exists on addressing study participants' involvement in research studies according to economic status of the areas where the studies are conducted. Regulatory authorities need to reach a compromise, rather than dictate the level, type or amount. Currently, there is a huge demand for biomedical research or trial populations, especially in areas still developing and carrying the burden of diseases. Africa has abundant virgin testing grounds for new tools produced by biomedical and genomic revolution, and vaccines for several infections challenges. This is compelled by the great diseases burden with easy to reach sample size. Rarely are requests for conducting studies in the African populations denied due to the scarce and poor health facilities, hence communities and the leaders would be expecting access to some improved health tools and products through hosting of studies. In such areas where capacity is lacking, the biomedical research activities being conducted may seldom be observed and monitored closely by the regulatory authorities and even by CABs who may not understand the scientific implications of such studies. The participant is found to be lowly considered and rarely consulted during the design of the study protocols rather everything is assumed from consultations with ministries and regulatory authorities. Major concern is that the community settlements are often dispersed and individuals find it difficulty to have a common stand. While in recent years it has come to light that some sponsors/funders are ready to accommodate as long as proposed in the line of expenditure by the investigating team towards study participant incentives, reimbursement and even compensation, since the sponsors sometimes have commitment to the community by providing services including alleviating poverty. The whole stages of considering compensation or even rewarding study participants has never been appropriately debated taking into account the concerns of the communities. While application of ethical principles has no mathematical formula, this has to take into account various prevailing factors that include economic, social, cultural religious, civil protection systems and other relevant factors. These factors may lead to procedural differences, but the spirit of the principle remains the same.

Some unscrupulous international and local researchers take advantage of the poor and uncoordinated research systems in resource-constrained areas. Rarely would local authorities keep keen track of the activities, and such a system is bound for abuse. Further, due to rampant poverty coupled with ignorance (in a sense), and sometimes there is prevailing abundant human rights abuses; this entail disregard of community rights and respect [ 15 - 18 ]. Most research activities require monitoring and this decision must be reached at planning level in comparison to studies conducted in other sites in developing countries. The African health challenges expose research participants, and also including researchers and institutions to exploitation, coercion, enticement and inducement [ 5 , 19 - 22 ]. Resource constrained communities are generally deprived of most common attributes of a well-sustained and democratic societies [ 23 , 24 ]. The basic human rights are not observed and the individuals, probably through ignorance or due to none existence, do not have any recourse to law [ 23 ]. This aspect is not available in African communities and sometimes the poor participant living in resource-constrained community can get assistance from NGO who attempt to lobby on their behalf [ 25 , 26 ]. However, critically analyzing the situation reveals a couple of stages where such mishap may be avoided during the planning stages of the proposal. The sponsor/funder, investigator, regulatory authorities assume not aware of this infringement on the participants. Through activities in immunological studies and parasitology surveys conducted in Zimbabwean communities; a study was conducted to investigate views and expectations of various stakeholders on study participation incentives, compensation and reimbursement issues.

Study sites

Eleven communities from districts in Zimbabwe participated in the study as follows: Burma Valley, Charehwa in Mutoko, Magaya and Chigono in Murehwa, Goromonzi, Kariba, Magunje and Karoi in Hurungwe, Shamva and Trelawney [ 27 - 43 ]. These rural districts are situated in areas where communities survive on subsistence farming, growing maize, groundnuts, sunflowers and soya beans. While a few of the communities survive on market gardening and small-scale irrigation activities. Data from 1,008 adult participants enrolled in the 11 intervention communities of biomedical studies were included in this analysis. The observations in school children involved about 1,450 school children (95%CI: 120-173 per school) in 10 rural schools. We excluded individuals who were not willing to respond to the questionnaire at the baseline data collection points. Responding to the questionnaire at baseline indicated willingness to participate even though such individuals may not have participated at other subsequent follow-up time points.

Data collection

Data was collected in various methods including a survey. The survey of parents/guardians of school children participating in various immunological cohort and parasitlogy survey studies. Community advisory boards (CABs) members at 9 sites in the different study communities were also consulted and lastly 45 participants that including 40 Zimbabwean researchers and 5 international research collaborators. Community based field health workers who were part of the community and were also involved in study promotion and implementation activities collected data regarding participation. The field staffs were trained in interviewing and observation techniques, data recording, and participatory community motivation approaches. The field staff recorded willing participation indicators during the days of the follow-up with a structured, observational questionnaire. In addition, field staff recorded self-reported attendance at the end of the study follow-up point through a questionnaire. These were compared to the data recorded by the research teams at the field site and in the laboratory shown by the actual presence of the collected biological sample. In order to arrive at an outcome that describes willingness to participation, we selected six complementary survey indicators that measure multiple dimensions of potential willingness (Table 1 ). Based on this group separation, we used characteristics of participation in the groups to describe them in meaningful, qualitative terms: Group 1 = 'willing participants', Group 2 = 'moderate participants', Group 3 = 'availability of samples as willing to participate' Group 4 encouraged participants, Group 5 = 'organized participants' and Group 6 'participation due to self/community benefits.'

Indicators for study participation as classified according to groups and the rational or interpretation for analyses.

Statistical analysis

To identify patterns of study participation, we explored the quantitative distribution of study participation in terms of the six quantitative indicators (Table 1 ). Six differentiated groups were identified. To confirm the patterns of study participation we further examined the distribution of the willingness from samples obtained at examination day and the availability of samples, including reports from encouragement by the CABs as indicators. Willingness to participate measures in diverse communities and individual level characteristics were deduced between groups with data compared. The identified participation groups were then used in the comparison analyses. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) version 8.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA.

Ethical approval

The biomedical studies obtained ethical approval from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe and also for each area, local leaderships were consulted and permission granted [ 27 - 43 ]. The provincial medical and education directorates provided permission while at the community level; the community leaders and CABs were first consulted for the main biomedical studies and also accepted the study. Informed consent was obtained from community leaders, adult participants, parents or guardians of school children prior to implementation of the main biomedical projects.

The field-based monitoring staff assessed the biomedical research compliance during baseline examination and at each subsequent follow-up time point in different studies conducted over a period of 6 years, from January 2005 to December 2010. The median duration of studies was 2 years, range: 0.5 year - 4 years, in 11 community-based studies, giving a total of 26 time points. At the community level, on average there were 95 participants per site (95% CI: 73 - 117), with participation patterns observed and a questionnaire administered. A total of 9 community advisory boards were interviewed (median 8 members/community, 95% CI: 7-12). Five of the studies involved taking blood samples while the rest involved epidemiological parasitology surveys and treatment programmes.

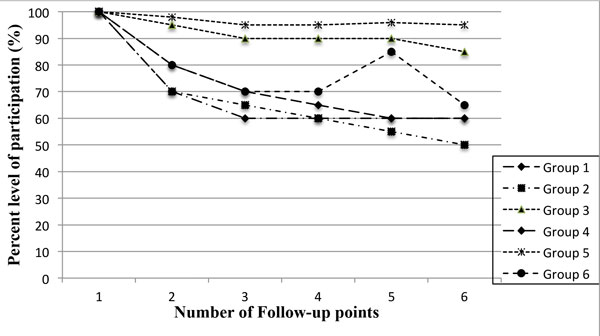

The level of participation varied, depending on the indicator used and the source of information. The encouragement by community-based staff (CABs) led to a moderate increase of 35% from the original 25% in the different communities. Participation compliance as observed by the research staff registered an increase during the follow-up visits where treatment was provided or a token of appreciation was given, with a median proportion of 80% (IQR: 65-95) in communities assessed. After 6 years of intensive research study implementation, the questionnaire administered by the research staff assessing study participation recorded 80% of respondents reported needing personal benefit from participation, and over 80% explicitly hinting on the need for revisions in determining the benefits for study participation. During the last intensive follow-up in each community the study staff deduced a declining willingness to participate, regardless of such benefits like provision of treatment for the examined parasite (Figure 1 ). By the end of the study, it was revealed that compensation and incentives were constantly being indicated as the main stimulation factor for adults' participation.

Showing the trends in levels of participation according to groups used in the analysis at different follow-up time points for the study sites summarized . The time points for each group may differ in year and type of study but the measurement was similar of the research subject willingness to participate.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the analysis, which identified six distinct participant groups based on purely on willingness to participate, and provision of all required samples as indicators. Group 5 (10 schools assessed), differed from the other groups with respect to the participants under observation as a type of a highly organized community with certain rules and regulation. While indicators 1 and 4 were more of community leaders and research staff noting upsurge of participation from records of samples obtained. These observations were noticed to decline with time into the study even though this recorded a high variability in all of the indicators as it was difficulty to base participation on the persuasion by the CABs members. Groups 2, 3 and 6 comprised indicators with the highest visible and tangible outcomes, while Group 2 with an initially high observation that declined over time, and group 4 showed a clear pattern when incentives were made available. Group 6 showed that regardless of the most important benefit to the participants of treatment available at no cost, participation was seen to decline drastically with time into the projected timeframe, an indication of probable participation fatigue. Table 2 , shows the difference between groups in 6 different participation indicators (research staff-reported, community observed) and two other monitoring indicators.

Level of attendance or provision of samples (%) at study sites for school children and adults relative to receiving incentives, compensation, re-imbursement and treatment

Table 2 , summarizes the need for compensation, incentives or re-imbursement through active participation at community level, through passive discussions with researchers and regulatory agents and at different institutions. Since the assessment/observation was standardized at community levels there is no difference between the six groups regarding features such as 'Number of follow-up events per community', 'Average number of participants per event and community', and 'Number of participation during the baseline and subsequently at each follow-up time point'. However, groups differed significantly regarding active participation at the events. School children in organized settings emerging to show high participation at all times at above 80% and 70% participation for parasitology/blood sampling and to receive treatment, respectively. The level of participation at school events was similar across groups, since participation was mandatory for school children in all schools in the study site (Table 2 ).

Participation group indicators correlated with each other and the estimates indicate that 'Total number of compliance by at least one indicator group' was positively associated with availability of samples of each group (Table 1 ). The results showed that availability of personal incentive, compensation or re-imbursement were more likely to enhance participation (OR: 3.38; 95% CI: 1.07-7.70) and to access any form of token given by researchers in community (OR: 2.02; 95% CI: 1.44-3.82). Furthermore, even school children from religious sector that do not take treatment was positively associated with increased participation when there is an incentive or a small token (provision of sweets or school writing notebooks) of appreciation (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.17-3.20); an increase from 70% to 80% to receive treatment and a further increase from 35% to 80% encouraged to know their infection status when an incentives was introduced (Table 2 ).

About 90% (907) of the study participants and guardians expected a reward of reasonable value, in view of the researchers' value and in comparison to what is offered at other sites regardless of economic status of the community. Discussion among researchers at a basic ethics training workshop indicated that 80% (32) believed the decisions on level of incentive should be determined by the local research ethics committees (Table 3 ). While, the few international research collaborators were of the opinion that reward or compensation should be in accordance with local guidelines, and in line with funding as agreed and documented in the protocol during the design and reviews. The study revealed that participants and guardians were not happy about decision on level and type of incentive, reimbursement or compensation being reached on behalf of study participants without considering their expectations. On considering expectations of reward revealed that researchers should consult CAB members since they represent the community. In contrast to the adult participants and guardians of children involved in studies, who were of the opinion that compensation and incentives should be at individual level. Both the CAB members and study participants expressed that there should be a clear distinction between study incentive and compensation according to individual and community benefits from studies. Finally, CAB members expressed that the regulatory authorities that normally cite concerns unknown to them, often moderate their suggestions.

Preference of incentives or compensation given to study participants.

Realization of ethical principles by study participants in communities starts with researchers as they draw out the proposed protocol. These are upheld or authenticated by the ethics committees through reviewers as the study protocol goes through assessment and the approvals process. Further, data safety and monitoring boards (DSMBs) try to observe that ethical guidelines are maintained and there is no prejudice while testing the study hypotheses. While the regulatory authorities (e.g. Medicines Control Authorities, Medical Research Councils, etc.) verify that ethical principles are adhered to and practised during the conduct of the studies. However, governments through the ministry of health and other ministries overseeing research, sometimes take advantage of the research activities to fulfil their own political promises using resources supposed to be research incentives. Very often it is not rare to find some policy makers twisting the regulations to achieve certain goals for the communities. While rarely advocacy groups including NGOs represent the community leaders and the voiceless participants.

Lack of empowerment exposes African research participants and even African researchers and institutions to exploitation, coercion, enticement and inducement that would compromise overall voluntariness, and even upholding fairness is research studies. The sponsor and the investigator must take every effort to ensure that the research is responsive to the health needs and priorities of the population or community in which it is to be carried out. If the capacity is lacking, steps must be taken to strengthen the oversight mechanisms [ 4 ]. Usually, some key players are easily identified with major responsibilities in research, however, the concern in determining the respect for the research participant is often over looked. Most guidelines refer to research participants as mere study components to be protected disregarding the need for rewards and individual benefits. The hierarchy in research authority and all responsible overseers should understand the demands and needs of the communities they protect. Research in resource limited areas need to have prescriptive guidelines that accounts for individual desires for rewards. The research participant is a living individual from whom a researcher obtains data and specimens. The investigation is performed on the research participant that means the individual is central to the activities. Researchers and all responsible authorities have ethical and legal obligations to protect and satisfy human participants universally [ 3 , 13 ].

The fundamental ethical principle of justice requires fairness or entitlement that is giving to each what is due. Human beings are morally equal and should be treated as such regardless of colour, creed, race or religion including economic status. This principle of justice demands fairness in treatment of individuals and communities as such there should be equitable distribution of the burden and benefits of research. Important implications for such issues include rewards to participants during the study and post-study benefits. Generally, the communities in resource-constrained areas still do not enjoy the fruits of study participation at an individual level. The fundamental principle of autonomy requires that the wishes and choices of an individual be respected [ 2 ]. Individuals in research studies must be their own masters and can act or make free choices and take decisions without constraint of another. This is rare where no individual opportunity is given to make an informed decision to ask if not demand for reward, rather level and the regulatory authorities presume the type of reward, and very often the principle of divide and rule is applied. No discussion is permitted even though consent is obtained. Most resource-constrained communities do not exercise their demand rights but are entangled in mob participation that is taken advantage of by the area regulatory authorities under the pretext of representing the participants.

Most communities involved in studies or clinical trials are presumed to understand the essence of research. Even with these assumptions, participants should be given adequate information and explanation hence this implies that they volunteer to be objects of some experiments. Even though being aware that it is not an obligation to participate in the research, most resource constrained communities and individuals flow together without demanding or exercising the right of being free to refuse participation. The success of research is highly dependent on the willingness and cooperation of the participants during the protocol activities, by providing information or specimens. Informed consent plays an important part in this regard [ 1 , 2 , 7 ]. The responsibilities often are weighted on the investigator even though there are considerable responsibilities on the research participant. In most instances, community representatives are a major player in decision making in as far as research participation. Researchers and trial sponsors need to consult communities through transparent and meaningful participatory process that involve participants during the early stages in the design, development, implementation and monitoring of the study activities [ 18 ]. Consultations maybe arranged through local community leaders such as headmen, chiefs, community health workers and local civic leaders. Most communities where research activities have been conducted, certain mechanisms have been established for community engagement by establishing community advisory boards.

Researchers or investigators have mammoth responsibilities that include extreme caution on the vulnerable populations. The Helsinki Declaration mentions the observation of the benefits to the community [ 1 ]. The Investigator must make evaluation on the benefits to the communities and or individual. The sponsor or investigator should make every effort to ensure the work is responsive to the health needs and the priorities of the population or community in which the study is being conducted. After the study or intervention, the knowledge generated should be made available for the benefit of the population or community [ 1 - 4 , 7 ].

One challenge of assessing the effectiveness of biomedical field research implementation is the lack of a reliable, unbiased and accepted indicator to measure participation. Compliance with the biomedical research programme and intervention (e.g. epidemiology project, clinical trials or testing clinical tools) is an important indicator of a successful implementation strategy. To our knowledge, none of the several studies that measured study participation in relation to compensation and giving out incentives as effectiveness to improve participation assessed determinants of compliance directly. To date, the most common end-points used to assess compliance rely on statistics deducted from successful follow-up as the indirect observation of willingness to participate and these indicators are often assessed once, usually at the end of the intervention, and the reliability of these indicators is unknown. Self-reported compliance in the context of an interview is known to produce inflated results due to reporting bias. In this study we use six measures of direct observation and researcher tallying attendance from sample availability to create a score to classify participation according to 'willingness to participate' by being present at examination and interview day, and 'provision of samples' as required on appropriate days. However, this approach to participation and availability of sample classification uses components that can readily indicate magnitude of willingness. Agreeing to be part of the study forces the investigator to subjectively determine the acceptance of the study by the community. There is a need for objective methods to classify participants into distinct willing groups and also to consider views of the CABs and other community leaders.

In this article we present a detailed analysis of research study compliance among participants from resource limited settings who participated in different community based studies in rural Zimbabwe. The assessment detected a highly statistically significant demand for incentive in school children and in adults with an overall compliance of above 80% based on both community- health worker assessment and the research staff. Here, we use research data collected over a number of studies whose participant compliance was monitored by CABs and the study researchers to objectively deduce participation. We then use the classified groups to describe the participation determinants that are associated with the general researcher-participant attitude in resource-constrained setting.

Systematic reviews of biomedical studies and clinical interventions in developing countries reveal that majority of the global inhabitants have somehow been reached by certain forms of research programme that demand their participation. Further, from empirical research data, the world is now becoming a village in as far as being accessed by study programs is concerned. The global research events indicate that it is becoming increasingly difficulty to isolate communities from what was practiced in other areas during conduct of research programs. Even justification for grossly different levels of incentives, compensation or reimbursement can no longer continue, as the world becomes a global village. There is need for collective consideration of both personal and community rewards in future studies to be conducted in resource-constrained communities. Information available indicates a projected fear that recruitment in future may be a challenge, now that almost every community has somehow been reached and participated in some form of research studies. A major concern is that study participation rewards should be internationally pegged regardless of different economic status of the individuals or communities.

The challenge for incentives, compensation or even reimbursement is addressed unequally between regions and development status of the community or country. Resource constrained communities welcome many forms of studies regardless of the exploitation levels, due to poverty. Most of these communities are not empowered to air out their demands. Further, in such communities there is no recourse to challenge irrational health research policies and administrative decisions. If research intellectual and legal rights can be shared equitably between researchers and their institutions - what is preventing individualized benefits to study participants? We characterized six distinct participation groups in studies conducted over 6 years among participants of school- and community-based studies in rural Zimbabwe. Participation characteristics that were most strongly associated with the categorized groups include giving incentives, the level of compensation or reward for time taken to participation. These three forms of study participant benefit were strongly associated with participation. Promotion of efforts to give the study participants something would more easily encourage participation, and presumably reduce recruitment time.

Our findings suggest that the motivation to provide samples and to participate; even for treatment requires some form of rewards. In addition, higher compliance and obtaining samples was associated with the frequency of issuing out some token of appreciation to promote individual attendance at sample collection time point. It is likely that eager participants providing the biological samples are more interested in participating at the related promotional events and with incentives. Applying the theory and belief of due influence if incentives are used, has no place in designing studies in the modern research programme. These coherent findings on the motivating factors for participation underscore the importance of determining form and level of incentive for the participants prior to implementing the project. In combining objective indicators that measured visible signs of willing participation (e.g. provision of biological samples or being present to give the samples especially blood samples for immunological work) with proxies indicative of responsive to CABs encouragement and the presence of the biological samples collected at the required time point increased the quality of measurement and reduced the potential for reporting bias. The CABs evaluation on compliance generated much lower willingness rates than research staff on actual sample availability observation. This underscores the potential for bias in situations where community based staff as members of the CABs evaluate their own work through compliance after mobilization. Our results highlight the importance of choosing independent staff and a valid and responsive indicator to assess willingness and compliance and to draw conclusions about the need or effectiveness of incentives in intervention programme.

Despite an intensive baseline and continuous mobilization campaign carried out by research teams and CABs members, we observed 35% overall compliance without any reward given out at subsequent follow-up time point. However, when incorporating a simple token or reward in the form of dried fish and cooking oil, participation increased to over 70%. While during the follow-up when the rewards were not available, there was a reasonable response to participation on the first day but when participant realized that nothing was being given out, the attendance dropped drastically. Introduction of a small token or reward during follow-up showed an increase to treatment uptake, even when giving out treatment with sweetened orange crush juice to a sector of school children from a religious group that does not accept treatment. Our findings suggest that biomedical research programme would benefit from reassessing the core requirement for compliance. According to information from resourced communities, there are stark differences in marketing messages and approaches to reach the critical fraction of the population to participate in such studies. Our analysis identified some characteristics associated with increased willingness to participate, after receiving a small token or reward, indicating the potential to draw community members to the study. Most of the concerns can be assessed and addressed during the writing up of the protocols and incorporated during marketing and promotion strategies targeting the participants and informing on the personal benefits and rewards from participation. Based on the characteristics that we measured, it was clear to differentiate the willing participant from 'incentive driven participation (Table 2 ). In the study, the population of the participant groups included the most marginalized rural communities by observable characteristics: they were poor, lived further from health services centres, rarely had enough daily resources, the communities have high prevalence of neglected tropical diseases. We give evidence of the need to include individual token of appreciation. But the agents involved in designing and reviewing the protocols rarely would agree to reward participants in whatever form that the communities would appreciate.

In the resource constrained areas context, programme planning may benefit from assessing easy measurable factors like the individual desires and community expectations, a large proportion of population subgroups in these poor communities that can be targeted for biomedical research sites do not have excessive demands for compensation or rewards at individual level. Those insights supported by our data are consistent with recommendations for a successful rollout of clinical trials programme deriving from other previous studies. Central government suggested levels of appreciation for the communities are not in line with what the community and individuals expect and sometimes rarely would the communities receive these contributions from the researchers. Normally, it is not uncommon that resources from research programme get diverted or replaces government responsibilities, hence individual senior government officials mat benefit from such confusion. Individual benefits should be considered separate from government responsibilities where these are required. As a result, regulatory authorities very often propose making use of community rewards from study programme for community developments, thereby portraying differences to studies conducted in resourceful areas. The difference in not permitting the rewards to an individual is beyond any reasonable thinking besides among those who wish to deny these communities their dues from participation in studies.

There are limitations to this study. The participating communities were not homogenous regarding preexisting infrastructures, previous exposure to research campaigns and biomedical programme, as well as political support to participate in the study. Finally, data on the willing to participate and comparable time points where a reward was introduced, may somehow differ because (i) the indicator was implemented by different groups, and (ii) availability of samples and presence to uptake treatment in non-invasive biomedical studies. We believe such measurements somehow enhanced the reliability of willingness to participate due to a direct visible benefit and none invasiveness of the study procedure.

Conclusions

Analyses of implementation effectiveness and the willingness to participate in research programme are rarely published. Our findings suggest that individuals from resource-constrained settings are marginalized in deciding their fate and desires for their participation in research studies. This finding suggests how researchers could identify from the communities where studies are to be conducted, the general wish for rewards of the populations most likely to encourage participation in studies. Introduction of such rewards would be greatly beneficial to clinical, epidemiological and other similar studies by reducing recruitment time frame in reaching desired sample sizes. The key finding here is that communities feel marginalized in decision making. There is no clear conclusion on the view of the stakeholders on participation incentives, compensation and re-imbursement. The subjects need awareness on their rights under the principles of Universal declarations of Bioethics and Human Rights and other international normative instruments on life sciences research ethics.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TM, NM, DD and PN conceived the idea and developed the design for the study. TM wrote the original draft manuscript, and incorporated revisions from each of the co-authors. NM and DD contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript and conducted the statistical analysis. TM and NM coordinated and supervised data acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the communities and the authorities of the Burma Valley District, Charehwa in Mutoko, Murehwa District, Goromonzi District, Kariba, Hurungwe, Shamva and Trelawney Districts. We acknowledge the collaboration with National Institute of Health Research, Ministry of Health & Child Welfare, Zimbabwe in the different research programme cited in this publication as part of their routine research programme on diseases of public health concern.

Funding for the study was part of the awards from Ministry of Health & Child Welfare, University of Zimbabwe Research Board funds, IFS and The Wellcome Trust. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Declarations

Publication of this supplement has been funded by the College of Health Sciences and the Research Office at the University of Kwazulu-Natal.

This article has been published as part of BMC Medical Ethics Volume 14 Supplement 1, 2013: Selected papers from the 3rd Ethics, Human Rights and Medical Law Conference (3rd EHMRL). The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcmedethics/supplements/14/S1 .