- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

Digital Humanities

- Creating Digital Humanities Projects

- Finding Data

Digital Humanities Resources, Methods and Tools

General purpose data analysis tools and resources, digital humanities in practice.

- Managing Data

- UCLA Digital Humanities Support

- Digital Humanities Beyond UCLA

- Introductory Resources

- Text encoding and analysis

- Digital mapping

- Network analysis

- Digital preservation

- Data visualization

- Collaborative research

- Virtual reality and 3D modeling

Here are some general-purpose resources for developing digital humanities projects.

For resources and tools related to specific DH methodologies, please explore the other tabs in this box!

Best Practices for Digital Humanities Projects

- A brief guide from the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska - Lincoln

Development for the Digital Humanities

- A resource for developing and managing digital humanities projects. Includes sections on formulating research questions, defining projects, making a plan for data, and many other crucial features of a DH project.

Digital History

- This book provides a plainspoken and thorough introduction to the web for historians who wish to produce online historical work, or to build upon and improve the projects they have already started in this important new medium.

Digital Research Tools (DiRT)

- Archived version (2019) of the DiRT Directory is a registry of digital research tools for scholarly use.

Introduction to Digital Humanities Course Book

- Adapted from DH 101 UCLA course

Programming Historian

- Peer-reviewed, hands-on workshop/tutorials

Visualizing Objects, Places, and Spaces: A Digital Project Handbook

- A guide to the essential steps needed to plan a digital project. You can learn more about various project types, or look at case studies and assignments to see what others have done. You can also submit your own work for inclusion.

Text encoding and analysie involves using computational tools to analyze large amounts of text, such as books, articles and manuscripts, to uncover patterns and connections that would be difficult to find by reading them manually.

Tools and resources for text encoding and analysis:

- Provides guidelines for structuring texts for digital analysis with project example

- This freely available book provides a practical introduction to natural language processing (NLP) using the Python programming language, and it includes many examples of how NLP can be applied to textual data in the humanities

- A web-based text-analysis tool

- A tool that allows users to develop concordances, find keywords, and develop word lists from plain text files

- Currently (2022), UCLA researchers have access to the free platform. Constellate allows you to build collections of content from multiple platforms (JStor, Portico, Chronicling America) as well as learn, teach, and perform text analysis ( Constellate tutorial list )

- a powerful tool for working with messy data: cleaning it; transforming it from one format into another; and extending it with web services and external data.

- Open source machine-learning toolkit. Topic models are useful for analyzing large collections of unlabeled text. The MALLET topic modeling toolkit contains efficient, sampling-based implementations of Latent Dirichlet Allocation, Pachinko Allocation, and Hierarchical LDA.

- Supports large-scale computational analysis of the works in the HathiTrust Digital Library to facilitate non-profit and educational research. Related: Programming Historian Python text mining tutorial for HathiTrust Research Center’s Extracted Features dataset

Digital mapping and spatial analysis involves creating digital maps and spatial analyses to study the relationships between people, places, and events in the past and present.

Tools and resources for digital mapping and spatial analysis:

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping software.

- Created by a global community of contributors, OpenStreetMap is a free, editable map of the world with an emphasis on local knowledge, existing as open data that can be used for research projects (or any other purpose) with proper credit

Network analysis and visualization involves using computational tools to analyze and visualize relationships between people, ideas, and events, in order to understand how they are connected and how they have changed over time.

Tools and resources for network analysis

- Free open source software for network analysis and visualization

- An open source software platform for visualizing complex networks

Digital preservation and archiving involves creating digital copies of historical and cultural artifacts and making them available online, with the goal of preserving them for future generations.

Tools and resources for digital preservation:

- Omeka is a free, flexible, and open source web-publishing platform for the display of library, museum, archives, and scholarly collections and exhibitions. Its “five-minute setup” makes launching an online exhibition as easy as launching a blog. To create maps and timelines, see Neatline , a suite of add-on tools.

- Collection Builder is an open source tool for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that are driven by metadata and powered by modern static web technology

- Drupal is an open source content management system for supporting resources like blogs and web sites

- A cross-platform XML editor that may be used to create and validate XML documents and associated schema

Data visualization is the process of using graphical representations to show the results of data analysis, such as graphs, charts, and maps, which can help to identify patterns and trends. See the UCLA Data Visualization Research Guide for more information.

Collaborative research and annotation is the practice of multiple researchers working together using digital tools and platforms to annotate, analyze, and interpret data.

Tools and resources for collaborative research and annotation:

- Supports semantic markup/annotation, named-entity recognition, Geo-names

- A semantic web authoring and publishing platform that supports various media annotations and multiple authors

- Annotate the web with anyone, anywhere

Virtual reality (VR) and 3D modeling involves using virtual reality and 3D modeling techniques to create immersive simulations of historical and cultural sites, which can be used for research and education.

Tools and resources for VR and 3D modeling:

- Free open source 3D creation software that provides tools for modeling, animation, and simulation

- 3D modeling software with a simple, user-friendly interface for creating 3D models and scenes

- A professional 3D animation software developed by Autodesk for more technically advanced users which provides a comprehensive set of tools for creating complex 3D models, animations, and simulations

- Introduction

- Other Resources

Here are some commonly used tools for data cleaning, statistical analysis and visualization.

UCLA offers various free and discounted licenses for some software products, so make sure to check the list before paying for a program.

Python is a programming language that enables data analysis.

- Download Python (free)

- Allows you to interactively write and execute Python in your browser with easy storage and sharing through Google Drive. It is a cloud-based version of Jupyter Notebook .

- Plotting and Programming in Python (Software Carpentries)

- The Python Tutorial (Python Documentation)

- Data Visualization with Python (GeeksforGeeks)

- Python Tutorial (W3Schools)

- Scikit-learn: Machine Learning Library

R is a programming language that enables data analysis.

- Download R (free)

- R Resources from UCLA OARC Stats Consulting

- Detailed Introduction to R

- R for Reproducible Scientific Analysis (Software Carpentries)

- R for Data Science

MATLAB is a proprietary programming language and numeric computing environment.

- How to Get Matlab (free for UCLA students, staff and faculty)

- Matlab Statistics & Machine Learning Toolbox

- Matlab Plotting (Tutorialspoint)

- Advanced Graphics and Visualization Techniques with MATLAB

Open Refine is a powerful tool for working with messy data: cleaning it; transforming it from one format into another; and extending it with web services and external data.

- Download OpenRefine (free)

- OpenRefine Introduction

- OpenRefine Documentation and Support

- Lesson on OpenRefine (Library Carpentries)

- Cleaning Data with OpenRefine (The Programming Historian)

- Fetching and Parsing Data from the Web with OpenRefine (The Programming Historian)

- Using OpenRefine to Clean Your Data (Berkeley Advanced Media Institute)

Tableau Software helps people see and understand data. Tableau allows anyone to perform sophisticated education analytics and share their findings with online dashboards.

- Tableau Download (free for full-time UCLA students)

- Tableau Getting Started Overview

- Tableau Help Guide (Princeton)

- Get the Microsoft Office 365 Education Suite (free for UCLA students)

- Data Analysis with Excel

- Excel Data Analysis Overview (Tutorialspoint)

Stata is a proprietary, general-purpose statistical software package for data manipulation, visualization, statistics, and automated reporting. It is used by researchers in many fields, including biomedicine, economics, epidemiology and sociology.

- Order Stata (discounted for students and education)

- STATA Resources from UCLA OARC Stats Consulting

- Stata User Guide

- Stata Coding Guide

- Online Stata Tutorial

- Getting Started in Data Analysis using Stata

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) is a software package used for the analysis of statistical data. Although the name of SPSS reflects its original use in the field of social sciences, its use has since expanded into other data markets.

- How to Get SPSS at UCLA

- SPSS Resources from UCLA OARC Stats Consulting

- SPSS Beginner Tutorial

ArcGIS is geospatial software to view, edit, manage and analyze geographic data. It enables users to visualize spacial data and create maps.

- ArcGIS Product Overview

- UCLA Guide: GIS & Geospatial Technologies

- UCLA Software Central: ArcGIS Overview

Stackoverflow

- A community where people can ask, answer, and search for questions related to programming

Software Carpentries

- Lessons to build software skills, part of the larger community The Carpentries which aims to teach foundational computational and data science skills to researchers

- Cloud-based service website based on Git software that allows develops to store and manage their code, especially helpful for version control during collaboration. The Software Carpentries has a lesson on Git and Github where you can learn more

Open Data Tools

- List of tools and resources to explore, publish, and share public datasets with sections specifically for visualization, data, source code, and information.

Data Science Notebooks

- List of interactive computing platforms for data science, includes comparison table at the bottom of the page

- Open graph visualization platform, well-known as a tool for network visualization

- Digital Humanities Projects

- Digital Humanities Journals

DH Projects at UCLA:

- UCLA Library Digital Collections This link opens in a new window Rare and unique digital materials developed by the UCLA Library to support education, research, service, and creative expression, including the AIDS Poster Collection, the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive and more.

- AEGARON: Ancient Egyptian Architecture Online Provides vetted and standardized architectural drawings of a selection of ancient Egyptian buildings.

- Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

- Digital Karnak Archived version of this resource.

- Hypercities

- UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Other DH Projects:

- Ancient World Mapping Center The Ancient World Mapping center hosts maps, articles, images of artifacts, and bibliographies of the ancient world. Tools used on this project are: XML, TEI, CSS2, JAWS for Windows.

- The Complete Writings and Pictures of Dante Gabriel Rossetti The Rossetti Archive features materials by and about the nineteenth-cenury Victorian painter, designer, writer and translator, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Among the resources on this website are books, manuscripts, correspondence, pictures, and poems. The tools used are: Collex, XML.

- Digital Black History A free, searchable directory for online history projects that can help further Black History research. This ongoing project was created to collect information about these digital Black History projects in order to benefit historians, genealogists, and family historians who are researching the lives of Black individuals and families.

- Documenting the American South This project is a digital puclishing initiative that provides Internet access to texts, images, and audio files related to Southern history, literature, and culture.

- East London Theater Archive The East London Theatre Archive provides online access to resources of music hall and variety theatres in London's East End during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The tools used in this project are: Fedora Commons, Javascript, MySQL, and PHP.

- Eighteenth-Century Book Tracker Links to freely-available digital facsimiles of eighteenth-century texts available at sites like Google Books and the Internet Archive.

- Mark Twain Project The mark Twain Project offers access to a variety of Mark Twain's writings, including texts, exhaustive notes, recently discovered letters, and documents relating to the author. Tools used in this project are: XML, STF, TEI, METS, MADS, MODS, DTD

- The Monastic Wales Project The Monastic Wales project fetures primary sources, secondary literature, maps, bibliographies, and articles on the monastic history of Medieval Wales. The tools used on this project are: MySQL, PHP.

- Valley of the Shadow The Valley of the Shadow provides details about the lives of two communities, one Northern and the other Southern, during the Civil War. Included are original diaries, letters, newspapers, speeches, census and church records. Tools used: Apache Lucene, Apache Solr, Cocoon.

- The Walt Whitman Archive Research and teaching tool for the study of Walt Whitman, containing material from libraries and collections all over the world.

- The William Blake Archive "The Blake Archive was conceived as an international public resource that would provide unified access to major works of visual and literary art that are highly disparate, widely dispersed, and more and more often severely restricted as a result of their value, rarity, and extreme fragility."

- The World of Dante A multi-media research tool intended to facilitate the study of the Divine Comedy through a wide range of offerings, e.g. an encoded Italian text which allows for structured searches and analyses, an English translation, interactive maps, diagrams, music, a database, timeline and gallery of illustrations.

Electronic Journals:

- The Digital Humanities Quarterly (DHQ) Digital humanities is a diverse and still emerging field that encompasses the practice of humanities research in and through information technology, and the exploration of how the humanities may evolve through their engagement with technology, media, and computational methods. DHQ seeks to provide a forum where practitioners, theorists, researchers, and teachers in this field can share their work with each other and with those from related disciplines.

- Digital Humanities Quarterly The mission of the DHQ includes experimenting with publication formats and the rhetoric of digital authoring, collaborating with ADHO's flagship print journal, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, in order to bridge the print-divide, using open standards in delivering journal content, facilitating international participation while developing translation services allowing multilingual review.

- Digital Studies / Le Champ Numerique Published three times a year, this peer-reviewed multilingual and interdisciplinary journal focuses on emerging digital humanities methodology and its application. This journal is also licensed under a creative commons attribution 3.0 license.

- Vectors: Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular This semi-annual journal utilizes emergent and transitionsl media to publish works on social, political and cultural issues.

- First Monday Ths peer-reviewed online journal publishes articles on the subject of the Internet and information technology. With articles on the subjects of digital libraries, digitization, metadata, and the humanities in the digital age, First Monday proves to be a valuable resource in the study of the Digital Humanities.

- Journal of Digital Humanities The Journal of Digital Humanities is a comprehensive, peer-reviewed, open access journal that features the best scholarship, tools, and conversations produced by the digital humanities community in the previous quarter.

- Journal of Cultural Analytics

- Journal of Open Humanities Data Great resource for published data-sets

- Reviews in DH is the pilot of a peer-reviewed journal and project registry that facilitates scholarly evaluation and dissemination of digital humanities work and its outputs

Subject Specific:

- Digital Medievalist This online peer-reviewed journal publishes articles on technological topics that relate to humanities computing and digital media relevant to the study of medieval history.

- 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth 19 is an open-access, scholarly, refereed web journal dedicated to advancing interdisciplinary study in the long nineteenth century. 19 publishes two themed issues annually, each consisting of a collection of peer-reviewed articles showcasing the broadest range of new research in nineteenth-century studies, as well as special forums advancing critical debate in the field.

- Contemporary Aesthetics In recent years aesthetics has grown into a rich and varied discipline. Its scope has widened to embrace ethical, social, religious, environmental, and cultural concerns. As international communication increases through more frequent congresses and electronic communication, varied traditions have joined with its historically interdisciplinary character, making aesthetics a focal center of diverse and multiple interests.

Non-Peer Reviewed:

- Journal of Electronic Publishing Published by the Scholarly Publishing Office of the University of Michigan University Library, this journal focuses on the methods and means of contemporary publishing and digital communication.

- Text Technology: The Journal of Computer Text Processing The online journal of the Society for thei Digital Humanities / Société pour l'étude des médias interactifs dedicated to sypplying articles relating to the use of computers in analysis and creation of texts. Article topics include professional and academic writing and research, analysis of texts, electronic publishing, software and book reviews, and issues relating to the internet.

- Digital Humanities Now Digital Humanities Now showcases the scholarship and news of interest to the digital humanities community through a process of aggregation, discovery, curation, and review .Digital Humanities Now also is an experiment in ways to identify, evaluate, and distribute scholarship on the open web through a weekly publication and the quarterly Journal of Digital Humanities.

- << Previous: Finding Data

- Next: Managing Data >>

- Last Updated: Oct 28, 2024 1:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/digital-humanities

- Digital Humanities

- Getting Started

- Digital Scholarship Services

- Mapping and Timelines

- Storytelling

- Text Analysis

- Visualization

- Static Sites & Minimal Computing

- Communities

Search Words for Researching Digital Humanities

You may also wish to conduct research in databases specific to your discipline.

Try these recommended search terms in general databases:

- Computational Humanities

- Computational Linguistics

- Computational Text Analysis

- Computerization

- Critical Editing

- Digital Collections

- Digital History

- Digital Image Processing

- Digital Library

- Digital Media

- Digital Resources

- Digitization

- E-Humanities

- Electronic Scholarship

- Electronic Text

- Hermeneutic Informatics

- Humanities Computing

- Image-Based Computing

- Literary Data Processing

- Quantitative methods

- Text Encoding

- Textual Analysis

- Textual Informatics

- Virtual Library

Journals & Databases

From Kairos (1996-) and Digital Humanities Quarterly (2007-), to newer launches like Reviews in Digital Humanities (2020-), DH journals facilitate conversations in the field.

The following list includes top journals as well as several field-specific publications:

- 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long 19th Century 19 is an open-access, scholarly, refereed web journal dedicated to advancing interdisciplinary study in the long 19 publishes two themed issues annually, each consisting of a collection of peer-reviewed articles showcasing the broadest range of new research in nineteenth-century studies, as well as special forums advancing critical debate in the field.

- Digital Humanities Quarterly An open-access, peer-reviewed, digital journal covering all aspects of digital media in the humanities. Published by the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO).

- Digital Medievalist This online peer-reviewed journal publishes articles on technological topics that relate to humanities computing and digital media relevant to the study of medieval history.

- Digital Studies Refereed academic journal serving as a formal arena for scholarly activity and as an academic resource for researchers in the digital humanities.

- First Monday This peer-reviewed online journal publishes articles on the subject of the Internet and information technology. With articles on the subjects of digital libraries, digitization, metadata, and the humanities in the digital age, First Monday proves to be a valuable resource in the study of the Digital Humanities.

- Game Studies Game Studies explores the rich cultural genre of games in the effort to give scholars a peer-reviewed forum for their ideas and theories and provide an academic channel for the ongoing discussions on games and gaming.

- Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication A broadly interdisciplinary web-based peer review journal. Its focus is social science research on computer-mediated communication via the internet, the World Wide Web, and wireless technologies. Full Text online 1995-Present.

- Journal of Computer Assisted Learning Covers the whole range of uses of information and communication technology to support learning and knowledge exchange.

- Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy Open access, openly peer reviewed journal to "promote open scholarly discourse around critical and creative uses of digital technology in teaching, learning, and research."

- Kairos Kairos is a refereed open-access online journal exploring the intersections of rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. First published in 1996, Kairos is the longest continuously-publishing online peer-reviewed journals in the field of digital rhetoric.

- Literary & Linguistic Computing Covers all aspects of computing and information technology applied to literature and language research and teaching.

- Reviews in Digital Humanities Edited by Dr. Jennifer Guiliano and Dr. Roopika Risam, this peer-reviewed journal and project registry facilitates scholarly evaluation and dissemination of digital humanities work and its outputs.

Zotero: Open DH Bibliographies

- Doing Digital Humanities

- Digital Humanities Group Listings Open collections of articles on many topics in the DH field.

- << Previous: Research

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Oct 10, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/digital-humanities

Digital Humanities in Practice: From Research Questions to Results

Use data science to enhance your research.

Combine literary research with data science to find answers in unexpected ways. Learn basic coding tools to draw insights from thousands of documents at once.

What You'll Learn

From the printing press to the typewriter, there is a long history of scholars adapting to new technologies. In the last forty or fifty years, the most significant advance has been the digitization of books. We now have whole libraries—centuries of history, literature, and philosophy—available instantaneously. This new access is a wonderful benefit, but it can also be overwhelming. If you have hundreds of thousands of books available to you in an instant, where do you even start? With a bit of elementary code, you can study all of these books at once, and derive new sorts of insights.

Computation is changing the very nature of how we do research in the humanities. Tools from data science can help you to explore the record of human culture in ways that just wouldn’t have been possible before. You’re more likely to reach out to others, to work across disciplines, and to assemble teams. Whether you're a student wanting to expand your skillset, a librarian supporting new modes of research, or a journalist who has just received a massive cache of leaked e-mails, this course will show you how to draw insights from thousands of documents at once. You will learn how, with a few simple lines of code, to make use of the metadata—the information about our objects of study—to zero in on what matters most, and visualize your results so that you can understand them at a glance.

In this course, you’ll work on building parts of a search engine, one tailor-made to the needs of academic research. Along the way, you'll learn the fundamentals of text analysis: a set of techniques for manipulating the written word that stand at the core of the digital humanities.

By the end of the course, you will be able to apply what you learn to what interests you most, be it contemporary speeches, journalism, caselaw, and even art objects. This course will analyze pieces of 18th-century literature, showing you how these methods can be applied to philosophical works, religious texts, political and historical records – material from across the spectrum of humanistic inquiry.

Combine your traditional research skills with data science to find answers you never might have expected.

The course will be delivered via edX and connect learners around the world. By the end of the course, participants will:

- Understand which digital methods are most suitable to meaningfully analyze large databases of text

- Identify the resources needed to complete complex digital projects and learn about their possible limitations

- Download existing datasets and create new ones by scraping websites and using APIs

- Enrich metadata and tag text to optimize the results of your analysis

- Analyze thousands of books with digital methods such as topic modeling, vector models, and concept search

- Test your knowledge by writing and editing code in Python, and use these skills to explore new methods of search

Your Instructors

Stephen Osadetz

Faculty Director of "The Digital Humanities in Practice" and Associate of the Department of English at Harvard University Read full bio.

Cole Crawford

Software Engineer, Humanities Research Computing at Harvard University Read full bio.

Christine Fernsebner Eslao

Metadata Technologies Program Manager for Harvard Library Information & Technical Services at Harvard University Read full bio.

Ways to take this course

When you enroll in this course, you will have the option of pursuing a Verified Certificate or Auditing the Course.

A Verified Certificate costs $219 and provides unlimited access to full course materials, activities, tests, and forums. At the end of the course, learners who earn a passing grade can receive a certificate.

Alternatively, learners can Audit the course for free and have access to select course material, activities, tests, and forums. Please note that this track does not offer a certificate for learners who earn a passing grade.

Related Courses

Data science principles.

Data Science Principles gives you an overview of data science with a code- and math-free introduction to prediction, causality, data wrangling, privacy, and ethics.

Shakespeare's Life and Work

Moving between the world in which Shakespeare lived and the present day, this course will introduce different kinds of literary analysis that you can use when reading Shakespeare.

Religious Literacy: Traditions and Scriptures

Led by Harvard faculty, this course will help you learn to better understand the complex ways that religions function in historic and contemporary contexts.

- Getting Started

- Choosing Digital Methods and Tools

- Learning Digital Methods

- Data and Digital Materials

- DH/DS Communities

- Funding and Grants

Digital Scholarship Publications and Conferences

- DSH: Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (formerly Literary & Linguistic Computing ) is an international, peer-reviewed journal (Oxford University Press, on behalf of EADH and ADHO ) which publishes original contributions on all aspects of digital scholarship in the Humanities including, but not limited to, the field of what is currently called the Digital Humanities. Long and short papers report on theoretical, methodological, experimental, and applied research and include results of research projects, descriptions and evaluations of tools, techniques, and methodologies, and reports on work in progress.

- DHQ (Digital Humanities Quarterly) is an open-access peer-reviewed journal from The Association for Computers and the Humanities . Launched in 2007, DHQ publishes articles, reviews, case studies, and opinion pieces on all aspects of digital humanities, as well as guest-edited thematic and language-specific special issues.

- Digital Studies / Le champ numérique is a refereed academic journal that serves as an Open Access area for formal scholarly activity and as a resource for researchers in the Digital Humanities. DS/CN articles focus on the intersection of technology and humanities research, including on the application of technology to cultural, historical, and social problems, on the societal and institutional context of such applications, and the history and development of the field of Digital Humanities.

– Digital cultural heritage with a special focus on born digital documents / archives – Data visualization, information retrieval, statistical analysis, big data – Natural language processing, named entity recognition, topic modelling, text mining – Digital scholarly editing – Semantic web technology, network theory – 3D modelling, digital visualization – Teaching Digital Humanities

- Cultural Analytics is an open-access journal dedicated to the computational study of culture. Its aim is to promote high quality scholarship that applies computational and quantitative methods to the study of cultural objects (sound, image, text), cultural processes (reading, listening, searching, sorting, hierarchizing) and cultural agents (artists, editors, producers, composers). Articles combine theoretical sophistication, computational expertise, and grounding in a particular field towards the crafting of thought-provoking arguments about how culture works at significantly larger scales than traditional research. Cultural Analytics publishes in three sections: Articles, Data Sets, and Debates.

- Kairos is a refereed open-access online journal exploring the intersections of rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. Since its first issue in January of 1996, the mission of Kairos has been to publish scholarship that examines digital and multimodal composing practices, promoting work that enacts its scholarly argument through rhetorical and innovative uses of new media. Kairos publishes “webtexts,” which are texts authored specifically for web publication.

- Computational Linguistics is the longest-running publication devoted exclusively to the computational and mathematical properties of language and the design and analysis of natural language processing systems. This highly regarded quarterly offers university and industry linguists, computational linguists, artificial intelligence and machine learning investigators, cognitive scientists, speech specialists, and philosophers the latest information about the computational aspects of all the facets of research on language.

- Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative , the official journal of the Text Encoding Initiative Consortium , publishes selected papers from the annual TEI Conference and Members’ Meeting and special issues based on topics or themes of interest to the community or in conjunction with special events or meetings associated with TEI.

- The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy (JITP) promotes open scholarly discourse around critical and creative uses of digital technology in teaching, learning, and research. “Educational institutions have often embraced instrumentalist conceptions and market-driven implementations of technology that overdetermine its uses in academic environments. Such approaches underestimate the need for critical engagement with the integration of technological tools into pedagogical practice. The JITP will endeavor to counter these trends by recentering questions of pedagogy in our discussions of technology in higher education. The journal will also work to change what counts as scholarship—and how it is presented, disseminated, and reviewed—by allowing contributors to develop their ideas, publish their work, and engage their readers using multiple formats.”

- Humanist Studies & the Digital Age is devoted to the study and reformulation of received philological and philosophical ideas of writing and reading in the Digital Era. It is part of the Directory of Open Access Journals.

- The International Journal for Digital Art History seeks to gather current developments in the field of Digital Art History world-wide and to foster discourse on the subject both from Art History and Information Science.

- The Journal of Data Mining & Digital Humanities is concerned with the intersection of computing and the disciplines of the humanities, with tools provided by computing such as data visualization, information retrieval, statistics, text mining by publishing scholarly work beyond the traditional humanities.

Defunct / Inactive

- The Journal of Digital Humanities has been on hiatus since 2014. It was a comprehensive, peer-reviewed, open access journal that features scholarship, tools, and conversations produced, identified, and tracked by members of the digital humanities community through Digital Humanities Now .

- Frontiers in Digital Humanities is now closed for submission. Its goal was to publish rigorously peer-reviewed research from Digital History to Big Data, providing a community platform for the Humanities in the digital age.

- Computers in the Humanities Working Papers were “an interdisciplinary series of refereed publications on computer-assisted research” (1990s-2009).

- Vectors last published in 2013. Operating at the intersection of culture, creativity, and technology, the journal focused on the myriad ways technology shapes, transforms, reconfigures, and/or impedes social relations, both in the past and in the present. Utilizing a peer-reviewed format and under the guidance of an international board, Vectors featured submissions and specially-commissioned works comprised of moving- and still-images; voice, music, and sound; computational and interactive structures; social software; and more – works that need to exist in multimedia.

- Digital Literary Studies last published in 2016. It published scholarly articles on research concerned with computational approaches to literary analysis/criticism, or critical/literary approaches to electronic literature, digital media, and textual resources.

Conferences

- Digital Humanities is the annual ADHO (Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations) conference and the largest event in the field. It is typically held between late June and early August, and rotates each year between North America, Europe, and the rest of the world. DH 2022 will be held in Tokyo, Japan, and DH 2023 will be held in Graz, Austria.

- The Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH) holds a biannual conference in the US.

- IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) typically holds a late fall working meeting and a spring / summer conference each year . The 2020 conference was scheduled to be hosted by Harvard in Boston, but has been postponed. The 2021 conference is free and online and will take place from June 22-24.

- HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory) is an interdisciplinary community of humanists, artists, social scientists, scientists, and technologists changing the way we teach and learn. The annual HASTAC conference is hosted by affiliate locations around the globe. The Spring 2022 HASTAC Conference will be hosted by the Pratt Institute in NYC.

Book Series

- Debates in the Digital Humanities (University of Minnesota Press) is a hybrid print/digital book series that explores debates in the field as they emerge. With biannual volumes that highlight current issues in the field, and special volumes on topics of pressing interest, Debates in the Digital Humanities tracks the field as it continues to grow.

- Digital Culture Books: Digital Humanities (University of Michigan Press) features rigorous research that advances understanding of the nature and implications of the changing relationship between humanities and digital technologies. Books, monographs, and experimental formats that define current practices, emergent trends, and future directions are accepted.

- Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities (Routledge) covers a wide range of disciplines and provides an authoritative reflection of the ‘state of the art’ in the application of computing and technology. The titles in this peer-reviewed series are critical reading not just for experts in digital humanities and technology issues, but for all scholars working in arts and humanities who need to understand the issues around digital research.

- Topics in the Digital Humanities (University of Illinois Press)

- Digital Humanities: Knowledge, Thought and Practice (OpenBook Publishers) presents cutting-edge research that investigate the links between the digital and other disciplines paving the ways for further investigations and applications that take advantage of new digital media to present knowledge in new ways.

Twitter and Blogs

Blogs and Twitter are usually the fastest way to hear the latest DH research, as well as all the news that doesn’t make it into a refereed publication.

Twitter Lists

- In progress: DH Organizations, Centers, and Publications

- In progress: DH People

- Ben Schmidt

- Found History (Tom Scheinfeldt)

- The Scottbott Irregular (Scott Weingart)

- Sample Reality (Mark Sample)

- Miriam Posner

- Frontiers in Computer Science

- Human-Media Interaction

- Research Topics

Artificial Intelligence: The New Frontier in Digital Humanities

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the field of humanities is a landmark event, signaling a transformation in the approaches to studying human culture and history. This paradigm shift is reshaping the traditional ways in which we conduct research, analyze information, and share insights. AI ...

Keywords : digital humanities, AI-driven cultural analytics, AI for heritage conservation, ethics of AI in humanities, AI tools in archival access, LLMs in humanities, virtual and augmented reality in humanities, human behavior analysis, digital health archiving, intellectual property management

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Making and interpreting: digital humanities as embodied action

- Zhiqing Zhang 1 ,

- Wanyi Song 2 &

- Peng Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5087-2112 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 13 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6223 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Complex networks

- Cultural and media studies

Digital technology has created new spaces, new realities and new ways of life, which have changed the way people perceive and recognise the world. In particular, the production, dissemination and reception methods of literature and art have been impacted upon significantly. Acknowledging humanities scholars have been engaged in conducting research while theorising and debating what Digital Humanities (DH) is/is not in the past two decades, this study extends current thought on DH by connecting it with the concept of sociological body, particularly thinking bodily interaction in relation to digital technologies in DH practice. The increasingly deepening integration of body and technology allows DH practice to become an event, in which embodied bodily action is situated in the (digital) environment that impacts on knowledge production. Acknowledging contemporary discourse regarding the two waves of DH, the article pays attention to the presence of the body whereby DH practice is bodily inclusive as mediated by digital technology, in which bodily interaction in producing knowledge via technologies reflects haptic experience and cultural constraints upon the sociological body. At the same time, technologies are not an innocent medium but an active contributor, so much so that we claim knowledge produced with the substantial involvement of digital technology is ‘digitised’ knowledge, as our critical interpretation towards a possible DH 3.0 practice that is subject to the core value of the humanities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Research progress and intellectual structure of design for digital equity (DDE): A bibliometric analysis based on citespace

Embracing the digital landscape: enriching the concept of sense of place in the digital age

Evolution of mediated memory in the digital age: tracing its path from the 1950s to 2010s

Introduction.

Embracing the current academic tide that favours interdisciplinary research as a means to break boundaries and achieve the integration of disciplines, Harpham ( 2006 ), the former director of the National Humanities Center in U.S., notes that questions formerly reserved for the humanities are being approached by scientists in various disciplines, such as cognitive science, cognitive neuroscience, artificial life, and behavioural genetics. Acknowledging digital technologies have energised humanities research, the emerging field of Digital Humanities (DH) is a response to the transformation of humanities in the digital age. It is worthwhile reminding ourselves that the essential problem of humanity in a computerised age remains the same as it has always been; that is, the problem of not solely how to be more productive, more comfortable, more content, but also how to be more sensitive, more proportionate, more alive (Cousins, 1966 ). DH has interdisciplinary and even anti-disciplinary attributes since its inception, Footnote 1 even though the very definition of DH is still being debated. This article draws on the concept of the sociological body in interdisciplinary terms by thinking bodily embodiment and haptic experience in relation to DH practice whereby the increasing integration of body and technology allows DH to be seen as an event; that is to say, as an embodied body in a digitally situated environment forming information and producing knowledge.

Digital Humanities, initially called Humanities Computing, is broadly humanities-based field involving scholars in the research areas of literary studies, history, media studies, musicology, and many other fields which benefitted from bringing computing technologies into the study of humanities materials. DH originated in the pursuit of more accurate objectivity and comprehensiveness in research beyond traditional methods in the humanities, such as McGann’s ( 2013 ) study on library research on how digital technologies can provide easier access to primary materials and increase the speed of searching and comparison. In cultural analytics, research can be conducted through the use of quantitative computational techniques which offer massive amounts of literary or visual data analysis (Manovich and Douglas, 2009 ), allowing for the visualisation of large amounts of data where patterns emerge. Acknowledging humanistic scholarship is either in the traditionalist mode of individual sensibility or in the contemporary mode of social critique, DH articulates a different understanding of the nature of meaning, which is “to speak to the larger patterns and deeper meanings of human experience…[and is] a modern technological incarnation” (Fuller, 2020 , 260, 262). The well-known example is the difference between distant readings versus close readings of texts in literary study (Moretti, 2013 ).

DH scholars are those who either adopt digital technologies in studying questions that are traditional to the humanities, or use values of traditional humanities in questioning digital technologies. Nevertheless, humanities research is increasingly being mediated through digital technology. Acknowledging efforts to theorise DH as a new discipline in which the debate on the boundary of DH is continuing and has not been settled over the past two decades, DH is intimate to humanities research, given the increasing number of research done in/via ‘charticles’, or journalistic articles that combine text, image, video, computational applications and interactivity in the humanities (Stickney, 2008 ). Kirschenbaum ( 2012 ) notes that various DH scholarly approaches reflect their interest in making in DH by, for example, creating digital archives, digital visualisation and possible new digital methods for (re)exploring social and cultural concerns. McGann notes that the main value of DH work resides in the creation, migration, or preservation of cultural materials ( 2008 , 2014 ). Meanwhile, other scholars emphasise interpretive work as a critical reflection, such as the interpretation of DH production in terms of its social and cultural impact. Although the digital approach can lead to a different understanding of large-scale cultural, social and political processes, it is actualised in concrete actions and reactions of operating digital technologies reflected as decision making on, and interpretation of, the inclusion/exclusion of data, for example. Thinking bodily interactions, humanities and digital technology altogether is to focus on the making in practice with the presence of body and haptic knowledge. In other words, technologies are not innocent; the knowledge produced with the substantial involvement of digital technology is ‘digitised’ knowledge, thereafter the bodily digital is formed.

While Manovich questions what culture is after it has been “softwarized” ( 2009 ), this article acknowledges, following Berry, that “understanding digital humanities is in some sense then understanding code, and this can be a resourceful way of understanding cultural production more generally” (2011, 5). In other words, the computer together with software is “the new engine of culture” (Manovich, 2013 , 21) and DH is where it takes effect. The article uses an interdisciplinary approach to think through the everyday use of digital technology in professional practice and research activity as an embodied act, in which one’s bodily action can be the critical interpretation in the process of knowledge making, such as bodily movement in manipulating digital technologies. Bodily making is critical interpretation. The mingling between physical and virtual space is ever strong, enabled and accelerated by the development of technology, such as immersive bodily experience by TeamLab. There is no longer a need to divide actual and virtual spaces, but rather take the body in action that is acting, reacting and crossing spaces constantly while knowledge is produced, in which ‘digitised’ embodiment and the bodily digital are formed. Rethinking DH via the concepts of situatedness and embodied bodily actions is to think DH practice as dynamic event, being in the world and beyond a discipline.

This article argues that DH practice is an embodied act in experiencing the impact of digital technology upon bodies, whereby new bodily knowledge, inclusive of the haptic and the visual, emerges in the process of action and reaction in collaboration with digital tools across actual and virtual space. The article, via analytical discussion, conceptualises and sees digital technology as not an innocent tool or neutral medium, but rather a series of concrete actions and reactions of bodily interactions with actuality and virtuality, where the knowledge co-produced is ‘digitised’ knowledge. The article, therefore, begins with a literature review that revisits the core value of traditional humanities, followed by stating the changes brought about by virtual reality, and then presents various concerns and some conceptual analysis of distinct and diverse aspects of scholarly works in the two waves of DH. The research method descripts the ensuing analytical discussion built on from previous works in terms of the concepts of situatedness and embodiment as a theoretical lens. The findings are elaborated on and theorised in the penultimate section conceptualising the bodily inclusive in DH practice by thinking bodily interaction, humanities, and digital technology altogether to produce ‘digitised’ knowledge via two case analyses.

Literature review

Criticalness–core value of humanities.

Criticalness, along with debate, pluralism and inquiry for instance, is the essence of the humanities, and the role of humanities scholars is crucial in the production and interpretation of cultural materials. There is a need to identify the values in DH which Spiro proposes are openness, collaboration, experimentation, collegiality and connectedness, and diversity and experimentation (2012a; 2012b). How the values of DH can be harnessed to enhance the humanities can be thought through in various ways; however, what is relevant to this article is in terms of bodily actions. Despite decades-long debate on DH’s role, value and relation to the humanities, much humanities research relies too much on digital technologies while critical awareness has weakened. For example, text can be quantified by forming conceptual indicators, yet the meaning temporarily fixed by researchers has limited explanatory power, thus highlighting the lack of criticism. Footnote 2 The humanistic pursuit of knowledge, which concerns subjective consciousness and is related to the viewer’s sensibility, cannot be processed by numbers themselves. In other words, in the current context of academic research ‘to have numbers’, scholars are concerned that art and literature works, for example, may only have data value after electronic transformation (Zhang and Zhang, 2021).

Becoming virtual

American scholar Lippmann proposed a concept in 1922 called “pseudo-environment” in his far-reaching book Public Opinion . Lippmann believes that newspapers, magazines and other media reconstruct a reality, which he calls a pseudo-environment. This pseudo-environment is an information environment, not an objective response to the real environment, but a new world created by the media, which shapes the audience’s picture of the real world in their minds (Lippmann, 1922 ). The original meaning of pseudo in English contains the meaning of ‘false’. Lippmann believes that the reality created by the media is not the reality that is faithfully reflected, but the reality constructed by the media organisation and the media organisation system; as long as the audience believes it, they exist in it. With the change of the media environment, the pseudo-environment, constructed by centralised media, such as newspapers and magazines, is a thing of the past. Instead, it has been replaced by the virtual environment based on the Internet. The virtual space is visual, distributed, and interactive involving user participation. While the pseudo-environment includes the participation of media organisations and ‘false’ elements in it, there is no such question of authenticity in the virtual space; or in other words, the liquid and User-Generated Content (UGC)-based new reality redefine the question of what is true and what is false.

The pseudo-environment has been replaced by virtual reality. For example, American science fiction writer Neal Stephenson published a novel Snow Crash in 1992 in which he created a space that did not exist—Metaverse. The Internet era is a digital era, and the virtual era is a dynamic and image era composed of Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR). The visual space created by virtual reality does not exist in one’s imagination, nor is it completely real, but offers a kind of new bodily experience and existence independent of matter and consciousness. Therefore, the advent of this virtual era ensured and advanced by digital technologies has affected not only people’s lifestyles, such as shopping and travelling, but the way people perceive and recognise the world through bodily experience.

Digital humanities

Digital Humanities (DH) research stems from the pursuit of objectivity and comprehensiveness in the research of the humanities (Piper, 2016 ). Based on a large amount of data, it attempts to conduct quantitative analysis on the subjectivity of the humanities and obtain some factual conclusions on this basis. Digital technologies have furthered this type of research and redefined DH as a response to the transformation of the humanities in the digital age. It is generally believed that DH is a field of academic activities where computer or digital technology intersects with the humanities. The pioneer of digital humanities recognised by academic circles is Roberto Busa, an Italian Jesuit priest. According to Jones ( 2016 ), Busa in collaboration with IBM in 1949 made an index consisting of more than 10 million words from the Latin works of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). This epoch-making achievement combined text and calculation for the first time, which greatly promoted the application of computers in the field of linguistics. In the 1960s, statistics began to join in, the most representative of which was the new research field of ‘authorship research’, which classified author texts by counting the frequency of word occurrence or the number of word occurrences, because each author is usually considered to have unique—yet very subtle—stylistic differences in the use of common words. A typical example of this is the study of the authorship of The Federalist Papers (1787–1788). Footnote 3 The first academic journal in DH, entitled Computers and the Humanities , was launched in 1966.

William Pannapacker declared the arrival of digital humanities at the annual meeting of Modern Languages Association (MLA) conference in 2009, which is the largest and most important association in the field of humanities in the United States. Many discussions have revolved around DH ever since, focussing on three core features. Firstly, DH digitises vast experiential materials and establishes (or utilises existing) databases to lay the foundation for analysis; secondly, it introduces statistical methods, conducts data mining, compares the significant characteristics of quantitative indicators, or discovers certain patterns, trends and regular phenomena; and thirdly, there is diversification and dynamic presentation of the research results.

The first wave

There are two widely known waves in DH. The first wave took place in the late 1990s focussing on digitisation projects. Moretti ( 2000 ) believes that to study world literature, neither ‘close reading’ nor comparative methods should be used, but a new ‘distant reading’ mode should be used, that is, using databases and quantitative methods, to explain the category factors and formal elements in the overall or broader text system. For example, by using a case study on published novels, Moretti exemplifies that the excessive number of novels cannot be understood by traditional methods in the humanities, but rather it is “a collective system, that should be grasped as such, as a whole” (2005/2007, 3–4). The impact of the first wave included data mining or large corpus processing and distant reading, which brought new insights and techniques into the humanities, as distinct from traditional methods such as close reading and textual analysis. The first wave was later summarised by Schnapp and Presner as “quantitative, mobilizing the search and retrieval powers of the database, automating corpus linguistics, stacking hypercards into critical arrays” (2009, 2). Previous discussions regarding the first wave resulted in many binary points of views, such as close reading versus distance reading, ‘panoramic’ collective view enabled by digital technology and big data versus individual intimate experience in traditional humanities, actual versus virtual, etc. Discussion regarding the binarism of digital technologies in humanities research seems to be diminishing with the arrival of the second wave of DH.

The second wave

The second wave called Digital Humanities 2.0 arrived in the late 2000s with more complexity and wider application in practice and theory; it “is deeply generative, creating the environments and tools for producing, curating, and interacting with knowledge that is ‘born digital’ and lives in various digital contexts…[and] introduces entirely new disciplinary paradigms, convergent fields, hybrid methodologies…” (Presner, 2010 , 68). Hayles notes that DH had emerged from “the low-prestige status of a support service into a genuinely intellectual endeavour with its own professional practices, rigorous standards, and exciting theoretical explorations” (2011, 46). Many scholars had recognised by then that DH is a new way of working with representation and mediation, such as Schreibman et al. ( 2008 ), Schnapp and Presner ( 2009 ), Berry ( 2011 ) and Hayles ( 2011 ); in Presner’s words, it is a new “Normal Humanities” (2010, 11). DH in general is a new scholarly method with its “focus on the identification of novel patterns in the data as against the principle of narrative and understanding” (Berry, 2011 , 13).

Schnapp and Presner note that the second wave is “ qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive, generative in character” (2009, 2, original emphasis). These characteristics of the second wave “harnesses digital toolkits in the service of the Humanities’ core methodological strengths: attention to complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation” (Schnapp and Presner, 2009 , 2). There are increasing number of scholarly practices across the humanities as shown in the examples below that reflect the characteristic applications, as well as the significance and impact of digital technology, in the second wave of DH. Before reviewing the three selected approaches in recent works of DH 2.0 that form the path to discussion on the importance of embodiment and haptic experience in this context, it is important to reiterate that this article acknowledges and extends upon the characteristics of DH 2.0 to propose a prospective on bodily action. The experiential, emotive and generative characteristics of DH 2.0 are every concrete bodily action actualised in the process of DH practice, while moving in and out of actual and virtual spaces, seeing the collective data through individual eyes, and conducting close reading on data from distance reading, etc. are rethought in terms of bodily action and lived experience. DH practice is bodily inclusive in which there is only bodily action to count on, a digital event as culturally embodied and spatially situated.

Recent research in DH 2.0 has addressed complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation, while many fields across the humanities have incorporated approaches and arguments from DH for their own core concerns. Of particular interest to this article, there are three selected approaches concerning cultural issues, minimising digital technologies in practice, and practicing in a situated space/place, which support the proposal for the bodily inclusive in DH practice that co-produces ‘digitised’ knowledge and becomes the bodily digital.

Firstly, concerns in traditional humanities involve digital technologies, such as the commitment of some DH scholars to antiracism and feminism discussions as well as Black studies. For example, Prince et al. ( 2022 ) call for a more equitable field based on the current challenging and difficult situation confronting DH Black scholars. Adams ( 2022 ) examines how Black fans use social media platforms to engage fandoms of contemporary Black popular cultural productions. Similar approaches in DH has been flourishing in cultural studies, gender studies, and minority/marginalised group studies in relation to topics such as colonialism (Alpert-Abrams and McCarl, 2021 ), feminist, queer and LGBTQ+ issues (Ketchum, 2020 ), exclusion of women and scholars of colour (Nowviskie, 2015 ), and how DH is reinforcing a gender gap in the field and a gendering of DH work itself (Wernimont, 2013 ; Olofsson, 2015 ; Mandell, 2016 ). The voices and opinions in the above groups across various studies are critical to understanding the social and cultural atmosphere and political climate, thereby forging a more inclusive path towards understanding society. The digital technologies engaged in the above research are seen as part of the social and cultural environment in facilitating the making of their qualitative comments as well as interpretations of their core concerns in the cultural domain.

Secondly, there is an enquiry about the necessity of using digital technologies, termed the concept of digital minimalism, or minimal computing according to Risam ( 2018 ). Gil ( 2015 ) questions “what do we need?” in an effort to reflect upon and recalibrate the increasing use of digital technologies. Wythoff ( 2022 ) notes that minimal computing focusses on “cultural practices rather than tools or platforms” and “prioritizes a humanist approach to technology”. Risam describes minimal computing as “a range of cultural practices that privilege making do with available materials to engage in creative problem-solving and innovation” (2018, 43). In actual practice, the concept is manifested as minimal design, maximum justice and minimal technical language (Sayer, 2016 ) to privilege wider access and openness to community. For example, Risam and Edwards ( 2017 ) practice minimal computing by embracing small data sets, local archives, and freely available platforms for creating small-scale digital humanities projects. Privileging making and shifting focus back on cultural practice in traditional thought, digital minimalism accommodates the impact of digital technologies and ensures wider access by reducing the use of high-tech and instead regarding digital technologies as merely tools and platforms. This approach is conscious of the body-tool relation and critiques the idea of ‘the more, or stronger, the better’. Despite partially disagreeing with digital minimalism’s strategy that seemingly has a sense of ‘withdrawal’ from, and reluctance towards, ever-growing digital technologies, we appreciate their thinking on making , which connects with bodily inclusive action in our argument. We thereby propose that the bodily inclusive in DH practices become digital events to embrace the ever-increasing use of digital technologies in everyday life. The full discussion on bodily embodiment in relation to digital technology is in the penultimate section of this article. Before that, we will outline the next approach concerning the DH lab/centre as a situated place/space that indirectly points to bodily actions taking place within, which is of interest to the article in terms of the emotive and generative sense of knowledge production/transfer in DH 2.0.

Thirdly, discussion on space and place is called situated research practice in DH (Oiva and Pawlicka-Deger, 2020 ), whereby research activities are typically undertaken in DH centres and laboratories in terms of ‘situatedness’. Many scholars argue that the DH lab/centre is more than a physical place. For example, based on a review of the ‘laboratory turn’ in the humanities, Pawlicka-Deger ( 2020 ) notes that the space and place of lab/centre has been conceptualised in relation to ways of thinking, communicating and working entailing new social practices and new research modes. There are five models of DH labs Footnote 4 that can be categorised and analysed to reflect the lab/centre as concept, initiative, and programme.

While the DH lab/centre is conceptually regarded as a problem-based project rather than a physical workspace, the emphasis is on collaboration, experimentation, and hands-on practices in the laboratorial space. That is to say, for example, “the manner in which the knowledge-transfer activities in DH communities are facilitated affects the knowledge they produce” (Oiva, 2020 ). Exploring the situatedness of DH lab/centre, Malazita et al. ( 2020 ) claim that “laboratory structures and cultures produce specific kinds of knowledge practitioners…[who] in turn produce and police the boundaries of legitimate and recognizable knowledge work…[a]ll of these productions are, in part, results of particular institutional and disciplinary positions”. Moreover, “knowledge is inseparable from the communities that create it, its context, structure, and the means with which it is produced and shared” (Oiva, 2020 ). Acknowledging the main idea of Oiva and Malazita et al. that it is important to understand the practices, structures, and the community underlying knowledge construction, we nonetheless argue there is also the presence of the body, which is culturally embodied and historically inherited, in the situated laboratorial space. Lived and immanent bodily interactions take place in the situated DH labs/centres and communities simultaneously while transferring/producing knowledge.

Bodily interaction actively constructs the DH lab/centre as a cultural space via the professional practice undertaken within as a dynamic process, an event of happening. Borrowing the concept of epistemic culture (Knorr Cetina, 1999 ), Malazita et al. ( 2020 ) point out that in terms of “the material and epistemic production of DH labs, their spaces, cultures, practices, and products…humanities scholars…must be produced as epistemic subjects through the interactions of their education, the objects, the field, and the documentary and critical writings about the objects”. To extend on this, movement in terms of the sociological body can add an extra lens to think through the situatedness of DH practice in a more complex and medium-specific way. The narrative of bodily movement is about historical context and analytical depth that is always engaged in critiques and interpretations.

Research method

The article proposes an alternative approach for DH practice as process-inclusive in the sense that bodily interaction, when operating or accommodating digital technologies while moving in and out of virtual and actual space for example, is itself critical and humane at a bodily level. The article builds on previous studies on embodiment (Liu, 2018 , 2022 ), actual and virtual space (Liu, 2020 ; Liu and Lan, 2020 , 2021 ) and bodily movement (Liu and Lan, 2021 ; Lan and Liu, 2023 ) to rethink bodily inclusive DH practice. After reviewing the discussion of DH 1.0 emphasising on the development of technology and analysis on cultural content, as well as of DH 2.0 with attention to complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation. Our proposal on the bodily approach in the process of knowledge making in understanding DH practice is particularly timely as the boundary, in terms of bodily experience, between actual and virtual space is increasingly blurred. In other words, the article predicts in the forthcoming Digital Humanities 3.0 wherein bodily accommodated digital technologies actively contribute to knowledge production in understanding the world.

The body, or the sociological body, has been extensively studied in a multitude of ways in sociological thinking and research by scholars such as Synnott ( 1993 ), Featherstone et al. ( 1991 ), Strathern ( 1996 ), Csordas ( 1994 ), Turner ( 1996 ), and Williams and Bendelow ( 1998 ); their intellectual contributions are discussed elsewhere and will not be repeated here. Since the body has been reconciled as “simultaneously a social and biological entity which is in a constant state of becoming” (Shilling, 1993 , 27), the body in this article is understood as a historically inherited and culturally embodied being (Liu, 2018 ) that is acted upon by institutions (Foucault, 1991 ). Bodily actions from everyday life—derived from the sociological concept of body techniques, or in Mauss’s term “the habitus” (1979, 101), which are “forms of embodied pre-reflective understanding, knowledge or reason…[that] distinguish and differentiate social groups” (Crossley, 2005 , 7–8) and have their own cultural interests and political motivations—are extended into the world of the virtual. Body technique is a “learned and incorporated skill” (Ravn, 2017 , 59), whereby the body first “act[s] to the skill qua thematized goal” and then acts “from” the skill (Leder, 1990 , 32) toward further goals. The body itself is in action to practice in DH research. The body in action, by exemplifying the disciplinary mechanisms or control in everyday society for example, is manipulating of, or being compromised by, digital technology; thereby, the bodily experience is impacted upon in ways of seeking, obtaining, selecting, analysing and interpreting data. Being subjective and critical in traditional humanities can be always present in DH, but co-produced with digital technologies.

Kinesics is the term coined in the study of bodily movements according to Birdwhistell ( 1952 ; 1970 ), which investigates and interprets nonverbal behavior (Ekman and Friesen, 1969 ), Footnote 5 such as facial expression (Raman and Singh, 2006 ), Footnote 6 gestures (Andersen, 1999 ), Footnote 7 posture (Pearse and Pearse, 2005 ; Patel, 2014 ), and bodily movements. Acknowledging studies conducted over the past decades with various emphasis and empirical parameters, bodily movement are taken as symbolic or metaphorical in social and cultural interaction. For example, body gestures (Kendon, 1981 ) and hand gestures (McNeill, 1992 ) are systemic and socially learned, Footnote 8 which touching behaviors and movements can express the internal state of a person of being arousal or anxiety (Andersen, 1999 ). The haptic experience of touching is tactile contact with oneself, objects, and others.

This article proposes a focus on the concrete actions of the body in practice mobilising/compromising digital technologies as an essential part of the research activity where new bodily experience emerges. The shift in focus to the bodily inclusive is timely in rethinking the current position of DH as being neither discipline nor interdiscipline. Instead, advanced digital technology, such as the forthcoming Web 3.0, is able to significantly narrow the boundary between virtual and actual bodily experience, whereby bodily inclusive DH practice can be seen as an event, a production itself; therefore, the embodied bodily movement is a critical response to research activities regardless of the research outcome. Humanities is the pursuit in which new knowledge is produced, and the anticipated Digital Humanities 3.0 is the process of experiencing in which new (digital) bodily experience is realised, thereby affecting the understanding of the world. In a parallel discussion, Fish ( 2012 ) notes, “Each reorganization (sometimes called a ‘deformation’) creates a new text that can be reorganized in turn and each new text raises new questions that can be pursued to the point where still newer questions emerge”, which implies that research is embedded in the ongoing process of (re)making and experimenting.

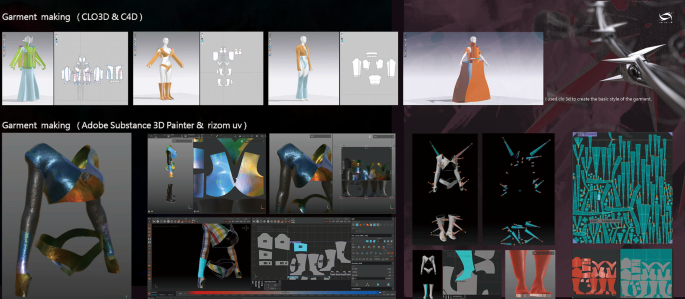

Therefore, moving away from debates concerning technology, method or criticalness etc., while embracing qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive and generative characteristics, thinking bodily action, humanities and digital technology altogether is to propose the situatedness of the bodily encounter in the process of making in the digital age. In this paradigm, the certainty of knowledge that researchers arrive at is not due to what things have been done but how things have been done upon every single bodily movement, wherein bodily experience is essential in knowledge making in the digital environment. Digital technology is more than a neutral medium, rather it has grown to actively contribute towards co-forming the realisation of the world. Two cases are examined to reflect DH practice as embodied action. The first is the practice of a fashion designer whose traditional garment making skills intertwine with digital technology resulting in new bodily experience and haptic knowledge in mixed realities. Footnote 9 The second reviews a research practice on an online community using data analysis in which the bodily inclusive proposes an alternative approach.

Digital Humanities 3.0 as embodied act: making, interpreting and criticalness

Kirschenbaum notes that DH is more akin to a common methodological outlook (2012), which perhaps downgrades the significance of DH and its potential to be a new space in comprehending and forming the world. Some scholars question whether the centre and the boundaries of DH remain amorphous (McCarty, 2016 ); Svensson ( 2016 ), for example, describes DH as being in a liminal state, that it is neither discipline nor interdiscipline. DH seems to have huge potentiality; however, at the same time, its promised future is continually delayed in which its highly anticipated impact has not yet been fully realised (Alvarado, 2012 ).