- Scientific Biographies

Michael Faraday

Best known for his work on electricity and electrochemistry, Faraday proposed the laws of electrolysis. He also discovered benzene and other hydrocarbons.

As a young man in London, Michael Faraday attended science lectures by the great Sir Humphry Davy. He went on to work for Davy and became an influential scientist in his own right. Faraday was most famous for his contributions to the understanding of electricity and electrochemistry.

Apprenticeship with Humphry Davy

The son of a poor and very religious family, Faraday (1791–1867) received little formal education. He was apprenticed to a bookbindery in London, however, and read many of the books brought there for binding, including the “electricity” section of the Encyclopedia Britannica and Jane Marcet ’s Conversations on Chemistry . He was also among the young Londoners who pursued an interest in science by gathering to hear talks at the City Philosophical Society.

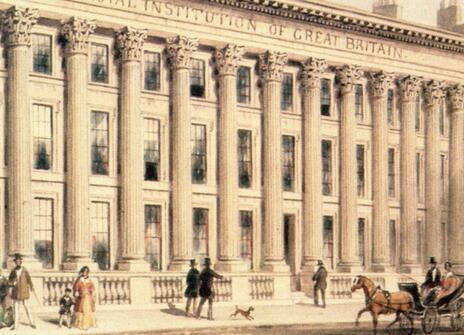

One of the bookbinder’s customers gave Faraday free tickets to lectures given by Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, and after attending, Faraday conceived the goal of working for the great scientist. On the basis of Faraday’s carefully taken notes of Davy’s lectures, he was hired by Davy in 1813. His first assignment was to accompany Sir Humphry and his wife on a tour of the Continent, during which he sometimes had to be a personal servant to Lady Davy.

Discovery of Benzene and Other Experiments

Once back in England, Faraday developed as an analytical and practical chemist. As his chemical capabilities increased, he was given more responsibility. In 1825 he replaced the seriously ailing Davy in his duties directing the laboratory at the Royal Institution.

In 1833 he was appointed to the Fullerian Professorship of Chemistry—a special research chair created for him. Among other achievements Faraday liquefied various gases, including chlorine and carbon dioxide. His investigation of heating and illuminating oils led to his discovery of benzene and other hydrocarbons, and he experimented at length with various steel alloys and optical glasses (for more on benzene, see August Kekulé and Archibald Scott Couper ).

Faraday’s Two Laws of Electrolysis

Faraday is most famous for his contributions to the understanding of electricity and electrochemistry. In this work he was driven by his belief in the uniformity of nature and the interconvertibility of various forces, which he conceived early on as fields of force. In 1821 he succeeded in producing mechanical motion by means of a permanent magnet and an electric current—an ancestor of the electric motor. Ten years later he converted magnetic force into electrical force, thus inventing the world’s first electrical generator.

In the course of proving that electricities produced by various means are identical, Faraday discovered the two laws of electrolysis: the amount of chemical change or decomposition is exactly proportional to the quantity of electricity that passes in solution, and the amounts of different substances deposited or dissolved by the same quantity of electricity are proportional to their chemical equivalent weights. In 1833 he and the classicist William Whewell worked out a new nomenclature for electrochemical phenomena based on Greek words, which is more or less still in use today— ion , electrode , and so on.

Light and Magnetism

Faraday suffered a nervous breakdown in 1839 but eventually returned to his electromagnetic investigations, this time on the relationship between light and magnetism. Although Faraday was unable to express his theories in mathematical terms, his ideas formed the basis for the electromagnetic equations that James Clerk Maxwell developed in the 1850s and 1860s.

In contrast to Davy, Faraday was known throughout his life as a kind and humble person, unconcerned with honors and eager to practice his science to the best of his ability.

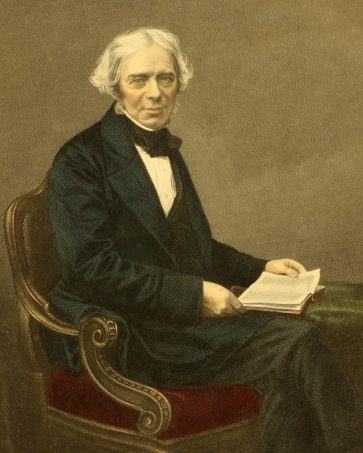

Featured image: Michael Faraday. Engraved by D. J. Pound from a photograph by Mayall. Science History Institute

Browse more biographies

Ralph Landau

Gordon E. Moore

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- American History ›

A Biography of Michael Faraday, Inventor of the Electric Motor

traveler1116 / Getty Images

Michael Faraday (born Sept. 22, 1791) was a British physicist and chemist who is best known for his discoveries of electromagnetic induction and of the laws of electrolysis. His biggest breakthrough in electricity was his invention of the electric motor .

Born in 1791 to a poor family in the Newington, Surrey village of South London, Faraday had a difficult childhood riddled with poverty.

Faraday's mother stayed at home to take care of Michael and his three siblings, and his father was a blacksmith who was often too ill to work steadily, which meant that the children frequently went without food. Despite this, Faraday grew up a curious child, questioning everything and always feeling an urgent need to know more. He learned to read at Sunday school for the Christian sect the family belonged to called the Sandemanians, which greatly influenced the way he approached and interpreted nature.

At the age of 13, he became an errand boy for a bookbinding shop in London, where he would read every book that he bound and decided that one day he would write his own. At this bookbinding shop, Faraday became interested in the concept of energy, specifically force, through an article he read in the third edition of Encyclopædia Britannica. Because of his early reading and experiments with the idea of force, he was able to make important discoveries in electricity later in life and eventually became a chemist and physicist.

However, it wasn't until Faraday attended chemical lectures by Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in London that he was able to finally pursue his studies in chemistry and science. After attending the lectures, Faraday bound the notes he had taken and sent them to Davy to apply for an apprenticeship under him, and a few months later, he began as Davy's lab assistant.

Apprenticeships and Early Studies in Electricity

Davy was one of the leading chemists of the day when Faraday joined him in 1812, having discovered sodium and potassium and studying the decomposition of muriatic (hydrochloric) acid that yielded the discovery of chlorine. Following the atomic theory of Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich, Davy and Faraday began to interpret the molecular structure of such chemicals, which would greatly influence Faraday's ideas about electricity.

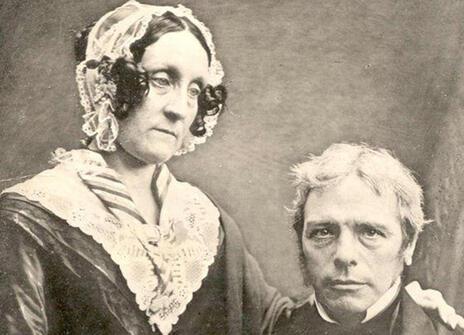

When Faraday's second apprenticeship under Davy ended in late 1820, Faraday knew about as much chemistry as anyone else at the time, and he used this newfound knowledge to continue experiments in the fields of electricity and chemistry. In 1821, he married Sarah Barnard and took up permanent residence at the Royal Institution, where he would conduct research on electricity and magnetism.

Faraday built two devices to produce what he called electromagnetic rotation , a continuous circular motion from the circular magnetic force around a wire. Unlike his contemporaries at the time, Faraday interpreted electricity as more of a vibration than the flow of water through pipes and began to experiment based off of this concept.

One of his first experiments after discovering electromagnetic rotation was attempting to pass a ray of polarized light through an electrochemically decomposing solution to detect the intermolecular strains the current would produce. However, throughout the 1820s, repeated experiments yielded no results. It would be another 10 years before Faraday made a huge breakthrough in chemistry.

Discovering Electromagnetic Induction

In the next decade, Faraday began his great series of experiments in which he discovered electromagnetic induction. These experiments would form the basis of the modern electromagnetic technology that's still used today.

In 1831, using his "induction ring"—the first electronic transformer—Faraday made one of his greatest discoveries: electromagnetic induction, the "induction" or generation of electricity in a wire by means of the electromagnetic effect of a current in another wire.

In the second series of experiments in September 1831 he discovered magneto-electric induction: the production of a steady electric current. To do this, Faraday attached two wires through a sliding contact to a copper disc. By rotating the disc between the poles of a horseshoe magnet, he obtained a continuous direct current, creating the first generator. From his experiments came devices that led to the modern electric motor, generator, and transformer.

Continued Experiments, Death, and Legacy

Faraday continued his electrical experiments throughout much of his later life. In 1832, he proved that the electricity induced from a magnet, voltaic electricity produced by a battery, and static electricity were all the same. He also did significant work in electrochemistry, stating the First and Second Laws of Electrolysis, which laid the foundation for that field and another modern industry.

Faraday passed away in his home in Hampton Court on August 25, 1867, at the age of 75. He was buried at Highgate Cemetery in North London. A memorial plaque was set up in his honor at Westminster Abbey Church, near Isaac Newton's burial spot.

Faraday's influence extended to a great many leading scientists. Albert Einstein was known to have had a portrait of Faraday on his wall in his study, where it hung alongside pictures of legendary physicists Sir Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell.

Among those who praised his achievements were Earnest Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics. Of Faraday he once stated,

"When we consider the magnitude and extent of his discoveries and their influence on the progress of science and of industry, there is no honour too great to pay to the memory of Faraday, one of the greatest scientific discoverers of all time."

- A Timeline for the Invention of the Lightbulb

- The History of Railroad Technology

- The History of the Electric Telegraph and Telegraphy

- History of Electric Christmas Tree Lights

- Historical Significance of the Cotton Gin

- Rudolf Diesel, Inventor of the Diesel Engine

- Significant Eras of the American Industrial Revolution

- History of the Sewing Machine

- The History of Radio Technology

- Overview of the Second Industrial Revolution

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- The History of Airplanes and Flight

- Edison's Invention of the Phonograph

- Henry Ford and the Auto Assembly Line

- Biography of Michael Bloomberg, American Businessman and Politician

- Notable American Inventors of the Industrial Revolution

Michael Faraday (1791-1867)

The discoveries of Michael Faraday, made in the basement of the Ri, shaped the modern world.

Ri positions

- Laboratory Assistant, 1813,1815-1826

- Director of the Laboratory, 1825-1867

- Fullerian Professor of Chemistry, 1833-1867

- Superintendent of the House, 1852-1867 (Acting 1821–1826) (Assistant 1826–1852)

Michael Faraday was born in Newington Butts, Southwark, the son of a Sandemanian blacksmith who had moved from the North West of England.

He served an apprenticeship with George Riebau as a bookbinder from 1805 to 1812. He was Assistant in the Royal Institution’s laboratory for part of 1813 and again from 1815 to 1826 (touring the Continent with Humphry Davy (qv) in the interim). He was appointed Assistant Superintendent of the House of the Royal Institution in 1821, Director of the Laboratory in 1825 and six years later the Fullerian Professorship of Chemistry was created for him. In the mid 1820s he founded both the Friday Evening Discourses and the CHRISTMAS LECTURES and delivered many lectures in both series himself. He was appointed Scientific Adviser to the Admiralty in 1829, was Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich between 1830 and 1851 and Scientific Adviser to Trinity House from 1836 to 1865.

His major discoveries include electro–magnetic rotations (1821), benzene (1825), electro-magnetic induction (1831), the laws of electrolysis and coining words such as electrode, cathode, ion (early 1830s) the magneto-optical effect and diamagnetism (both 1845) and thereafter formulating the field theory of electro-magnetism.

He was twice offered the Presidency of the Royal Society, but declined on both occasions. He publicly stated several times that he would not accept a knighthood, but no evidence has been found that he was ever offered one. He was, however, awarded a Civil List Pension in 1836 and in 1858 the Queen provided him with a Grace and Favour House at Hampton Court where he died.

Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Faraday's papers

The papers include laboratory notebooks, lecture notes and various publications, some administrative papers on the Royal Institution of Great Britain including cash books, correspondence regarding his work for the Admiralty and the Corporation of Trinity House whilst, general communication with people and other organisations. Other items include his book collection, scrapbooks, portfolio of portraits and apparatus.

Catalogue information is currently available on the National Archive's Discovery service and a summary of the collection can be found on the AIM25 website .

Other resources

A complete edition of Faraday's approximately 4900 extant letters is being published under the editorship of Frank James at the Royal Institution.

Find out more about the Correspondence of Michael Faraday

Book an appointment to view the archives

Publications

Faraday published only one book, Chemical Manipulation, Being Instructions to Students in Chemistry (1827). His other publications are collections of papers or lecture notes; his famous Chemical History of a Candle (1861) was edited and published by his friend William Crookes.

The other titles are collections of papers and lecture notes, some published after his death:

- Chemical Manipulation, Being Instructions to Students in Chemistry (1827)

- Experimental Researches in Electricity, Vol I, II & III (1837, 1844, 1855)

- Experimental Researches in Chemistry and Physics (1859)

- W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Various Forces of Matter (1860)

- W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (1861)

- W. Crookes. ed. On the Various Forces in Nature. (1873)

- The liquefaction of gases (1896)

Manuscripts which have been published

- Brian Bowers and Lenore Symons, ‘Curiosity Perfectly Satisfyed’: Faraday’s travels in Europe 1813‐1815, (London, 1991). Based on his papers held at the Institution of Engineering and Technology.

- Frank A.J.L. James, The Correspondence of Michael Faraday, (London, 1991‐2008). The complete correspondence of Michael Faraday consists of six volumes.

- Frank A.J.L. James, Guide to the Microfilm edition of the Manuscripts of Michael Faraday (1791‐1867) from the Collections of the Royal Institution, The Institution of Electrical Engineers, The Guildhall Library [and] The Royal Society, (2nd ed., Wakefield, 2001). The vast majority of Faraday’s manuscripts, apart from letters, published on microfilm and cd.

- Thomas Martin, Faraday’s Diary, 7 volumes and index, (London, 1932–36). A typescript edition of Faraday’s experimental notebooks with diagrams.

Explore Michael Faraday's life and work

History of science

A tour of michael faraday in london.

A walk from the Royal Institution to Somerset House exploring Faraday's life, his intellectual network and his legacy.

Michael Faraday's correspondence

A brief history of Michael Faraday's correspondence, from 1811–1867.

Michael Faraday's magneto-optical apparatus

The electromagnet used by Michael Faraday in a ground-breaking experiment showing that light and glass are affected by magnetism

Sarah Faraday (1800–1879)

Sarah Faraday was the wife of eminent Ri scientist Michael Faraday.

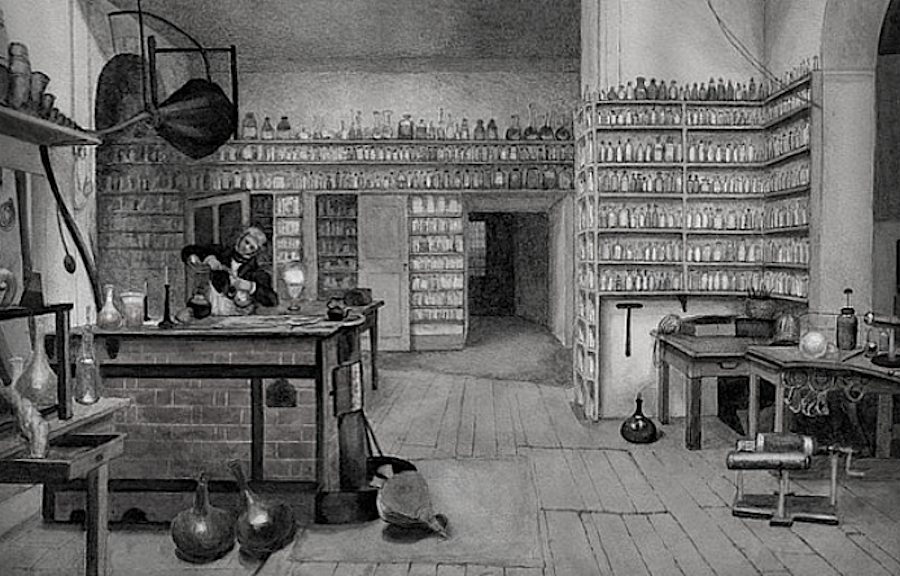

Michael Faraday's Magnetic Laboratory

The actual laboratory where Michael Faraday made his fundamental discoveries of the magneto-optical effect and of diamagnetism

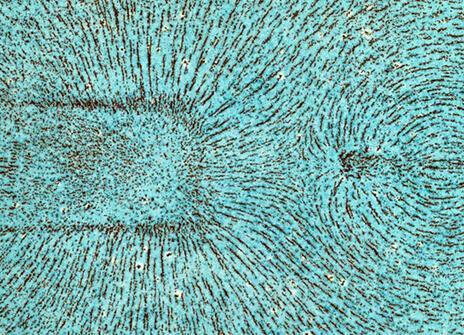

Michael Faraday's iron filings

Faraday created a number of iron filing diagrams in 1851 to demonstrate magnetic lines of force.

- International Advisory Board

- Michael Faraday

- Conferences

- Past Events

- Faraday Papers

- Science & Eternity

- Virtual Learning Environment

- Useful Links

- Churches Home

- About Faraday Churches

- Resources Menu

- Quick Links for Church Leaders

- Artificial Intelligence

Who was Michael Faraday?

The Faraday Institute is named after Michael Faraday because he combined a deep religious faith with an outstanding scientific career, making him one of the best known of all British scientists, or natural philosophers as they were known in his era. At the same time Faraday was a very effective communicator of the latest findings in science in the public domain, an exemplar of how to cross inter-disciplinary boundaries.

Early career

Michael Faraday (1791-1867) discovered many of the fundamental laws of physics and chemistry, despite the fact that he had virtually no formal education. The son of an English blacksmith, he was apprenticed at the age of 14 to a bookseller and bookbinder. He read every book on science in the bookshop and attended lectures given at the Royal Institution by various natural philosophers, including Sir Humphry Davy, the discoverer of several chemical elements. In 1812, he applied to Davy for a job, citing his interest in science and showing Davy the extensive lecture notes he had taken. Davy hired Faraday to assist with his research and lecture demonstrations.

Magnetism and chemistry

Within a few years, Faraday began to do original research on his own, submitting two papers on chemistry to the Royal Society in 1820. In that same year, Oersted discovered that a current in a wire deflects a compass needle. Faraday repeated Oersted’s experiments and found that a magnet also exerts a force on a wire carrying an electric current. Soon afterward, he also showed how to liquefy chlorine, and he isolated benzene, a fundamental component of organic chemistry.

Faraday’s important discoveries brought him considerable fame, much to the discomfort of Davy, who felt he should have shared the credit for some of the advances. Davy preferred to regard Faraday as a technical assistant and even forced him to serve as a valet on an extended tour of European research centres. Despite Davy’s objections, Faraday was elected to the Royal Society in 1824 and was made director of the laboratory at the Royal Institution in 1825.

Electricity

After Faraday discovered, in 1831, that a changing magnetic field can induce a current, he performed a series of experiments that showed clearly that the induced EMF is equal to the rate of change of magnetic flux. Also, generalizing from the patterns formed by iron filings around magnets, he invented the concepts of magnetic and electric field lines. Faraday knew little mathematics and found this concrete approach to electricity and magnetism much more useful than equations giving the forces between charges or currents. He also suggested that the propagation of light through space consisted of vibrations of these lines. His concepts of electric and magnetic fields were put into mathematical form a generation later by Maxwell, who showed that light is, in fact, an oscillatory electromagnetic disturbance.

Faraday made many other notable contributions. He devised the first electrical generator, which consisted of a copper disk rotating between the poles of a magnet. He discovered the correct laws of electrochemistry after proving that earlier theories disagreed with experiments. He studied optical phenomena and found that when light passes through a medium, a magnetic field will rotate the direction of the oscillating electric field. Ignoring scorn from his contemporaries, he attempted unsuccessfully in laboratory experiments to find a link between gravitation and electromagnetism. Such a link was observed 70 years later in a test of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, when light rays passing near the sun were found to be deflected.

During the years 1831-1855 Faraday read before the Royal Society a series of 30 papers that were published in his three-volume ‘Experimental Researches in Electricity’. His bibliography lists nearly 500 printed papers, of which only three were jointly written papers. Today we might call Faraday a physicist, but the term did not come into usage until the late 1860’s, and the description ‘chemist, electrician and natural philosopher’ more clearly describes the immense range of Faraday’s investigations. By 1844 he had been elected to about 70 scientific societies, but Faraday declined nomination as President of the Royal Society. As Cantor remarks ‘…as a Christian Faraday felt that no God-given moment should be wasted. His time had to be strictly controlled. He pursued both his science and his religion with total dedication’.

Work, finish, publish

Faraday’s advice to a younger scientist to ‘Work, finish, publish’, is an aphorism that would serve as a useful reminder on the wall of any modern laboratory. Yet Faraday still found time to take a keen appreciation in the arts, read novels vociferously and spent many hours a week visiting the poor and sick in the context of his job as an elder of his local church in London. In fact he was an enthusiastic collector of engravings, lithographs, and photographs, particularly portraits. He developed lasting friendships with many of the leading artists of London and served as an advisor to the British Museum, National Gallery, and Westminster Abbey on the preservation of sculpture and architecture.

One of Faraday’s jobs in the Royal Institution was to give regular public lectures that would bring the public up-to-date on the latest scientific discoveries. There was an immense public interest in science in early Victorian England. Nervous at the start of his new responsibility, Faraday soon became a confident and gifted lecturer, incorporating experiments into his lectures and quickly establishing a rapport with his largely non-specialist audiences. His obvious enthusiasm for his subject was infectious. ‘All is a sparking stream of eloquence and experimental illustration’ enthused William Crookes after one of Faraday’s lectures. Faraday rarely alluded to religion as such during his public lectures, but the religious message was implicit in the sense of wonder that he set out to evoke in the remarkable properties of God’s world. In a private lecture given before Prince Albert in 1849 Faraday expounded the wonders of magnetism and the influence that it appeared to exert on every particle in the universe: ‘What its great purpose is, seems to be looming in the distance before us….and I cannot doubt that a glorious discovery in natural knowledge, and of the wisdom and power of God in the creation, is awaiting our age’.

Christian convictions

Faraday belonged to a small nonconformist denomination and his Christian convictions shaped his attitude towards his science as much as to other aspects of his life. Faraday firmly believed in God as creator, but was critical of the natural theology that dominated much early Victorian science, and neither did he look to the Bible as a source of scientific information. Like Bacon, Faraday was convinced that the book of God’s world and the book of God’s word had the same author, so that ‘the natural works of God can never by any possibility come into contradiction with the higher things that belong to our future existence…’ The source of knowledge about salvation was derived from the Biblical revelation of God’s working in history through the people of Israel in the Old Covenant, and then by God sending his Son to die on the cross and rise from the dead in order to secure the New Covenant. Such knowledge could not be derived by investigations of the natural world, which were sufficient only to indicate God’s existence and power.

Faraday had a deep sense of the order of God’s creation. The laws of nature ‘were established from the beginning’ and so were ‘as old as creation’. The notes of one of his earliest lectures contain the pithy exhortation ‘Search for laws’. The task of science was to discover those laws by a process of empirical investigation. As Faraday argued in a memorandum (1844) on the nature of matter: ‘God has been pleased to work in his material creation by laws’ and ‘the Creator governs his material works by definite laws resulting from the forces impressed on matter’. The ‘beauty of electricity….[is] that it is under law’. ‘The laws of nature, as we understand them, are the foundations of our knowledge of natural things’, he told the audience at one of his lectures.

The ‘holy grail’ of the relationship between the various powers of creation was a topic to which Faraday frequently referred, though it was a topic still so speculative that Faraday confided many of his most ambitious thoughts only to his diary. On March 19, 1849, his diary records: ‘Gravity. Surely this force must be capable of an experimental relation to Electricity, Magnetism and the other forces, so as to bind it up with them in reciprocal action and equivalent effect. Consider for a moment how to set about touching this matter by facts and trial’. Many experiments followed, but Faraday was unable to detect any influence of falling objects on electric fields, reporting these negative results to the Royal Society in November, 1850. Nevertheless, concluded Faraday, although the results were negative, they ‘do not shake my strong feeling of the existence of a relation between gravity and electricity, though they give no proof that such a relation exists’. God’s world was coherent, ruled by law. In such a world relationships between forces had to exist.

Faraday’s legacy

Faraday was a brilliant iconoclast. Einstein remarked of Faraday that he, of all people, ‘had made the greatest change in our conception of reality’. Yet despite his achievements, Faraday remained a modest and humble person. He declined to be knighted or to receive honorary degrees and only reluctantly accepted a small pension on his retirement in 1858.

“Indeed, all I can say to you at the end of these lectures (for we must come to an end at one time or other) is to express a wish that you may, in your generation, be fit to compare to a candle; that, in all your actions, you may justify the beauty of the taper by making your deeds honourable and effectual in the discharge of your duty to your fellow-men”.

[Michael Faraday, closing his most famous Christmas series, ‘The Chemical History of a Candle’]

D.R. Alexander, ‘Rebuilding the Matrix – Science and Faith in the 21st Century’, Oxford: Lion, 2001, pp. 159-164.

G.Cantor, ‘Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist’, Macmillan, 1991,

C.A.Russell ‘Michael Faraday: Physics and Faith’, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion The Woolf Building Madingley Road Cambridge CB3 0UB United Kingdom

Tel +44 (0)1223 748888

Charity Commission for England and Wales: 1153702 Company Limited by Guarantee with Companies House: 08426223

Enter your details to receive a monthly newsletter from The Faraday Institute.

Join our newsletter

We take your data seriously, please read our privacy policy .

View the newsletter archive

- © 2024 The Faraday Institute. All rights reserved.

Web Design by Chameleon Studios

IMAGES

VIDEO