Experience Machine

What is the experience machine.

The Experience Machine is a thought experiment, which means it’s a kind of philosophical story designed to make us think about big ideas. It helps us to understand what truly makes us happy. Is it only about having all the pleasure we can imagine, or is there something special about the real experiences we have, even if they sometimes come with pain or trouble? The Experience Machine asks if we’d plug into a fake world that makes us feel great all the time, or if we’d rather stay in the real world, with all its ups and downs.

This big question comes from a famous philosopher named Robert Nozick. In 1974, he wrote about the Experience Machine in his book “Anarchy, State, and Utopia.” The Experience Machine he thought up can trick our minds into thinking we’re living any kind of life we want, filled with joy and without any bad parts. But Robert Nozick suspected that people wouldn’t choose to live this fake, perfect life because we care about more than just feeling good all the time. We value who we are, making real connections with others, and actually living through our experiences, even when it’s hard.

Definitions of the Experience Machine

The Experience Machine is like a super advanced video game that can make our brains believe we’re living any life we can dream up. It feels completely real and is programmed to make us feel nothing but happiness. The machine’s world is perfect, but it’s not the world we actually live in—it’s made up and controlled by this machine.

Imagine a virtual reality that’s so perfect you can’t tell it’s fake; that’s the Experience Machine. It creates a pretend life for us that’s so pleasing, we might prefer it to our real lives. But it’s like choosing to live inside a movie instead of the real world with everyone else. We have to decide: Should we pick a life full of pretend yet perfect moments, or should we keep living our true lives, complete with tough times and true achievements?

Key Arguments

- Pleasure versus Reality: The heart of the debate is whether fake, perfect happiness is better than real, sometimes hard experiences. It’s like deciding between only eating your favorite candy for the rest of your life or choosing a meal that might have some veggies you don’t like but is overall healthier for you.

- Understanding True Happiness: The Experience Machine suggests that what keeps us truly happy isn’t just a good feeling, but also knowing that our joys and triumphs are real. It’s like the difference between someone telling you a story that makes you laugh and actually living out a funny moment yourself.

- Limitation to Knowledge : If we were to choose the Experience Machine, we’d only know what the machine shows us. This implies we care a lot about really understanding the world and learning from our own experiences, not just being told what it’s like.

- Concept of Self-Identity: Who we are is shaped by the choices we make and the things we go through. The Experience Machine would take away our chance to build ourselves with the experiences we actually live.

Answer or Resolution

There’s no right or wrong answer when it comes to the Experience Machine question. Robert Nozick thought most of us would say no to the machine’s world of made-up happiness. This suggests that things like truth, growth, and being our genuine selves matter to us a lot, even more than endless pleasure. The ongoing conversation shows how complicated it is to figure out what makes life good and what happiness really means to each of us.

Major Criticism

Some people don’t agree with the arguments against the Experience Machine. They think that Nozick was unfair to pleasure, assuming everyone would pick a hard but real life over a pleasant fake one. After all, who wouldn’t want to feel great all the time and avoid all suffering? The thought that lots of people might pick the fake world of constant joy is a big point of disagreement between thinkers.

Practical Applications

- Virtual Reality (VR): VR might remind us of the Experience Machine because it lets people enter a world that feels real but isn’t. It makes us wonder about how real these computer-generated places are and what that means for us.

- Video Games: When we play video games, we can go on incredible adventures without leaving our homes. But this makes us question if these digital wins are as important as real-life achievements or friendships.

- Online Social Lives: How we act on the internet, especially on social media, can sometimes seem more perfect than our actual lives. This raises questions about whether we’re being true to who we are or just showing off a better but fake version of ourselves.

- Medical and Therapeutic Use: Technologies like VR can help people with pain or with healing from bad memories. Even though it might be helpful, it also asks us if it’s okay to use make-believe experiences to fix very real problems.

The Experience Machine is not just a tricky question but a tool that philosophers use to dig deep into what makes life worth living. For such a machine to appeal to us, it forces us to think about what we value most: a never-ending stream of happiness or the authentic journey of life with all its random, meaningful events. As technology blurs the line between reality and illusion, discussions like these help us navigate the choices we face. The Experience Machine keeps us questioning and talking about how we create meaningful lives, what happiness really is, and how we interact with the world of technology that’s growing around us.

Related Topics

Understanding the Experience Machine can open the door to exploring other big questions and related ideas. Here are a few:

- Hedonism : The philosophy that pleasure is the most important goal in life. It’s related because the Experience Machine shows the limits of hedonism—pleasure alone might not be enough for a fulfilling life.

- Realism vs. Idealism : This is about whether we should focus on the way the world really is (realism) or on how it could be in a perfect scenario (idealism). The Experience Machine pushes us to think about which perspective we lean towards.

- Authenticity: Being true to oneself and genuine in our actions. The Experience Machine challenges us to think about the importance of living an authentic life versus one that is artificially perfect.

- Simulated Reality: Like the plot in movies such as “The Matrix,” this idea questions whether what we experience is real or if we could be living in a simulation. It ties back to the Experience Machine by making us wonder about the nature of our own reality.

- Existentialism : A philosophy centered on individual freedom, choice, and personal responsibility. It’s connected to the Experience Machine because it underlines the significance of personal experiences and choices that define our existence.

Philosophical Disquisitions

Things hid and barr'd from common sense

Monday, January 23, 2017

Understanding the experience machine argument.

The Experience Machine : “Imagine a machine that could give you any experience (or sequence of experiences) you might desire. When connected to this experience machine, you can have the experience of writing a great poem or bring about world peace or loving someone and being loved in return. You can experience the felt pleasures of these things, how they “feel from the inside”. You can program your experiences for…the rest of your life. If your imagination is impoverished, you can use the library of suggestions extracted from biographies and enhanced by novelists and psychologists. You can live your fondest dreams “from the inside”. Would you choose to do this for the rest of your life?…Upon entering you will not remember having done this; so no pleasures will get ruined by realizing they are machine-produced.”

( Nozick 1989, 104 )

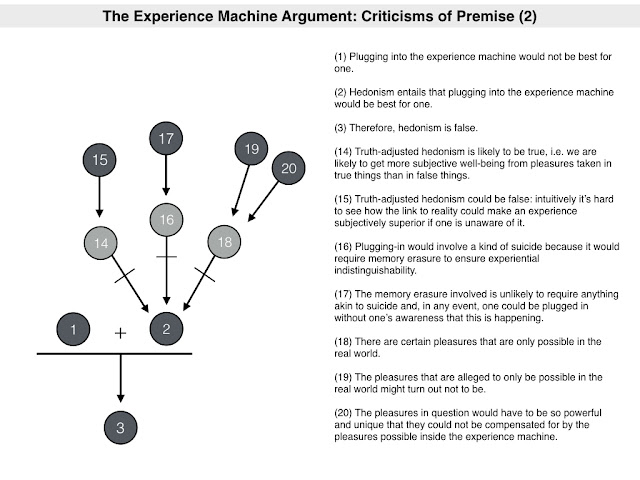

- (1) Plugging into the experience machine would not be best for one.

- (2) Hedonism entails that plugging into the experience machine would be best for one.

- (3) Therefore, hedonism is false.

- (4) The intuition against plugging in is, in fact, consistent with hedonism because it is based on a reasonable fear of catastrophe.

- (5) You can modify the thought experiment to remove sources of reasonable fear or run an alternative version where you ask people to compare to experientially identical lives, one of which is lived in an experience machine and one of which is not. If people still prefer the non-plugged-in life, premise one holds.

- (6) It is very difficult to construct a thought experiment in which people have a fine-grained intuition about hedonism: it is likely that their thinking about the scenario is contaminated by other moral/normative considerations.

- (7) In imagining the case, you can also imagine that other people “can plug in to have the experiences they want, so there’s no need to stay unplugged to serve them.

- (8) Our unwillingness to plug in might be due to an irrational fear, revulsion or bias.

- (9) “Nozick could gladly accept that an important part of the reason we would be unwilling to plug in is that we have an irrational fear, revulsion or bias…His gripe with hedonism stands: it does not seem best for someone to plug in to the machine.” ( Bramble 2016, 139 )

- (10) The Debunking Problem: The fact that our intuitions about the Experience Machine are affected by things like status quo bias gives us reason not to trust those intuitions.

- (11) Proponents of debunking need to explain how our intuitions about well-being got to be affected in this way: how do our conditioned or hardwired preferences get to affect our pre-theoretical feeling that contact with reality is an important part of well-being.

- (12) Proponents of debunking need to be challenged to identify some uncontaminated intuitions. Since, presumably, theories of well-being ultimately rest on some intuitive beliefs about what makes for the good life we need to figure out which ones we can trust.

- (13) Proponents of debunking need to explain how some people can have the intuition that connecting reality is important without the deeper desire or belief that connecting to reality in intrinsically important. (Bramble gives himself as an example of such a person)

- (14) Truth-adjusted hedonism is likely to be true, i.e. we are likely to get more subjective well-being from pleasures taken in true things than in false things.

- (15) Truth-adjusted hedonism could be false: intuitively it is hard to see how the link to reality could make an experience subjectively superior if one is unaware of it.

- (16) Plugging-in would involve a kind of suicide because it would require memory erasure to ensure experiential indistinguishability.

- (17) The memory erasure involved is unlikely to require anything akin to suicide and, in any event, one could be plugged in without one’s awareness that this is happening.

- (18) There are certain pleasures that are only possible in the real world.

- (19) The pleasures that are alleged to only be possible in the real world might turn out not to be.

- (20) The pleasures in question would have to be so powerful and unique that they could not be compensated for by the pleasures possible inside the experience machine.

3 comments:

I don't think hedonism should be the main focus here. It's pretty obvious that people can get fulfillment/happiness in virtual reality. Those who are reluctant to plug in are those with responsibilities and skepticism. What should be anticipated is the futuristic technology that will emerge, whether it be temporary memory erasure/suppression or a simulation that decently simulates real life. Without being able to consider even a fraction of the infinite nuances that will decide how many and what kind of people will plug in, guessing about this future isn't too much fun.. Also, I realize we all have a conscience for what must be "right" or "wrong," but that doesn't quite matter to the other seven billion plus apes. What matters is what many people want, which is awesome games when life isn't awesome. It may be a surprise to some people, but life isn't always awesome.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

I'm not convinced that there would still be some form of suicide, if only that of one's character. To plug in and experience all that you want, memory erased or maintained, removes the value of the real world and in my view the value of the person who dismisses those real experiences for those in the machine, if only because they are those which bring more pleasure.

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

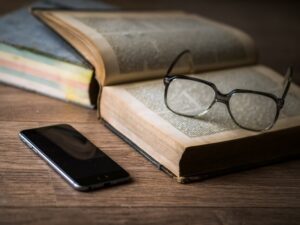

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Nozick’s Experience Machine: Does it Refute Hedonism?

Robert Nozick’s experience machine is commonly invoked to argue that there’s more to life than pleasure. This article outlines the thought experiment, and discusses why hedonists think it’s deeply flawed.

9 -MIN BREAK

W hat does it mean to live a good life? What makes a life intrinsically valuable? If we were to describe someone as ‘happy’, what quality or qualities would their life include?

To answer such questions, a common stance philosophers take is that of hedonism .

Not the kind of folk hedonism whereby someone indulges in endless carnal pleasures, but prudential hedonism , the philosophical position which states that, ultimately, when it comes to personal wellbeing, pleasure is the only intrinsic good, and pain the only bad.

While there are different types of hedonism, hedonists generally assert that, when you get right down to it, everything we recognize as ‘good’ — say, friendship, love, kindness, growth, solving problems, high achievement — is underpinned by feeling good. And everything we recognize as ‘bad’ — say, loneliness, vice, fear, shame, failure — is underpinned by feeling bad.

So, though living a good life can often seem like a very complicated matter, hedonists cut through this complexity to point out that, actually, it’s rather simple: living a good life means feeling good within ourselves . ‘Happiness’ is simply the preponderance of pleasure over pain.

Our approach to living well should thus be built around this insight: the good life involves experiencing more pleasure than pain.

This ‘pleasure principle’ is very influential in philosophy. It underpins, for instance, the philosophy of the ancient Greek thinker Epicurus , who advises us to approach our lives according to a hierarchy of pleasures (with long-term mental tranquility being the highest, and short-term physical pleasures being the lowest).

It forms the basis, too, of 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s ethical theory of utilitarianism, that “ it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.”

While hedonism is a popular and influential philosophical theory, however, it is not without its critics.

Isn’t there more to a good life than simply feeling good?

The philosopher Robert Nozick certainly thinks so, and in his 1974 book Anarchy, State, and Utopia he introduces a famous thought experiment aiming to knock down hedonism (along with other mental state theories of wellbeing) once and for all.

The Experience Machine

“S uppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience that you desired,” Nozick writes in Anarchy, State, and Utopia :

Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain.

The question is:

Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life’s experiences?

What do you think? Would you plug into the machine?

Nozick thinks most of us wouldn’t (and indeed shouldn’t).

And several empirical studies back up Nozick’s intuitions. Weijers (2014) , for instance, found that 84% of the participants asked about Nozick’s machine were averse to plugging in.

But, if the good life is only about having good experiences , as hedonists and proponents of other mental state theories of wellbeing claim, then why don’t we want to plug into a machine that guarantees good experiences?

What’s stopping us from plugging into the experience machine?

O f course, the simple answer — and the one Nozick wants us to have — is that we don’t want to plug into the experience machine because there is more to life than pleasurable experiences .

In other words, hedonism is false, for the good life is not just about feeling good, Nozick observes: we want to actually do something. We don’t just want to be a free-floating bundle of empty pleasures, we want to actually be a certain type of person. Nozick writes:

Someone floating in a tank is an indeterminate blob… Is he courageous, kind, intelligent, witty, loving? It’s not merely that it’s difficult to tell; there’s no way he is. Plugging into the machine is a kind of suicide.

The good life, then, is not just about having certain experiences, Nozick thinks: we want contact with reality . We want our lives to be rooted in the real.

As Nozick summarizes:

We learn that something matters to us in addition to experience by imagining an experience machine and then realizing that we would not use it.

However, while the experience machine is often taken as a knock-down argument against hedonism, some philosophers point out that the thought experiment exploits a number of psychological biases.

Sure, we might not want to plug into the machine — but that doesn’t mean not plugging in is the right answer, nor that hedonism is false; we are simply clouded by bias.

Once we expose that bias, the argument goes, we can see how Nozick’s thought experiment is no threat to hedonism whatsoever.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Consider: technophobia and the status quo bias

O ne immediate thing to point out is that Nozick’s thought experiment isn’t just about pleasurable experiences; it’s about giving ourselves over to a big scary machine that we do not understand.

By rejecting the machine, we are not necessarily rejecting pleasure, we are simply expressing our unease with technology.

Related to this worry is what philosophers call the status quo bias: that we irrationally tend to prefer the way things are.

This bias reveals itself when we reverse Nozick’s thought experiment, notes the philosopher Lorenzo Buscicchi in a 2022 essay :

Imagine that a credible source tells you that you are actually in an experience machine right now. You have no idea what reality would be like. Given the choice between having your memory of this conversation wiped and going to reality, what would be best for you to choose?

Empirical studies show that most people, given these circumstances, would choose to stay in the experience machine. Buscicchi observes:

Comparing this result with how people respond to Nozick’s experience machine thought experiment reveals the following: In Nozick’s experience machine thought experiment people tend to choose a real and familiar life over a more pleasurable life, and in the reversed experience machine thought experiment people tend to choose a familiar life over a real life. Familiarity seems to matter more than reality, undermining the strength of Nozick’s original argument.

According to the status quo bias, then, we reject the experience machine not because we reject pleasure for reality, but because we are uncomfortable with such a radical departure from our familiar lives — including the abandonment of all our existing commitments.

The hedonistic bias

A nother way philosophers defend hedonism from Nozick’s thought experiment is by claiming that, far from counting against hedonism, our aversion to plugging in is in fact motivated by hedonism.

Nozick suggests we have a desire to remain rooted in the real world — but what motivates us to have this desire? Why do we want to remain attached to reality? Might it not be because we think that, by staying attached to the real world, we will ultimately feel better within ourselves..?

The so-called ‘paradox of hedonism’ is instructive here: pleasure is often best pursued indirectly.

We rarely set out to simply grant ourselves pleasure; instead, we go for a walk, we spend time with our loved ones, we read a book, we work on a favored project — and thereby obtain pleasure.

As Epicurus observes , going after every single promise of immediate, short-term pleasure is not a good strategy for maximizing our pleasure overall, and so we often forgo short-term pleasures — and even tolerate pain — in order to secure longer-term pleasures like mental tranquility.

Nozick’s experience machine exploits this gap between short-term pleasure and longer-term pleasures. We are suspicious, perhaps subconsciously, that it offers pleasures only of the instant gratification kind, and thus reject it because we think that by staying attached to reality we have a better chance of attaining longer-term peace of mind — failing to realize that this longer-term peace of mind is itself a form of pleasure .

The philosopher Matthew Silverstein nicely articulates this view in his 2000 paper, In Defense of Happiness (note: he uses ‘pleasure’ and ‘happiness’ interchangeably):

[O]ur experience machine intuitions reflect our desire to remain connected to the real world, to track reality. But… the desire to track reality owes its hold upon us to the role it has played in the creation of happiness…. Our intuitive views about what is prudentially good, the views upon which the experience machine argument relies, owe their existence to happiness. We miss the mark, then, if we take our intuitions about the experience machine as evidence against hedonism…. Even though it leads us away from happiness in the case of the experience machine, our desire to track reality points indirectly to happiness…. The mere existence of our intuitions against the experience machine should not lead us to reject hedonism. Contrary to appearances, those intuitions point — albeit circuitously — to happiness. And as a result, they no longer seem to contradict the claim that happiness is the only thing of intrinsic prudential value.

So, according to this position, we reject the experience machine because we think our lives would feel better outside of it. Far from a rejection of hedonism, then, our response to the experience machine reveals our deep-rooted hedonic motivations.

The experience machine says nothing about the truth or falsity of hedonism

F inally, some philosophers argue that, regardless of whether we choose to plug in or not, our response to the experience machine actually says nothing about the truth or falsity of hedonism whatsoever.

We might not want to plug into the experience machine, but that doesn’t suddenly mean we can conclude that hedonism is false. That’s like arguing that (i) since we wouldn’t plug in, we aren’t hedonists and that (ii) since we aren’t hedonists, hedonism is false.

Harriet Baber expresses this argument well in her 2008 paper, The Experience Machine Deconstructed . She writes:

Regardless of what subjects choose, the Experience Machine cannot either confirm or disconfirm any philosophical theory of wellbeing. It merely tests the empirical hypothesis that informed choosers prefer hedonically optimal states.

In other words: all the experience machine thought experiment tests, Baber says, is whether we ourselves would choose lives of maximal pleasure / happiness.

Our suspicion towards this kind of life says nothing about whether pleasure / happiness is the only intrinsic good; it merely reveals that we are not very good at choosing what is best for ourselves.

Defending the experience machine

I n response to the concerns just raised, some philosophers offer staunch defenses of Nozick’s experience machine, tweaking the conditions of the thought experiment to account for certain biases, and to make it less focused on our own individual preferences.

Eden Lin, for instance, in his 2016 paper How to Use the Experience Machine , suggests that we can refocus the thought experiment to turn up the heat on hedonism as follows.

Suppose A and B have exactly the same lives, and go through exactly the same experiences. The only difference is that A lives in reality, and B is plugged into an experience machine.

Who has the better life?

If hedonism is true, then we must answer that the quality of A and B’s lives, the value of their lives, is exactly the same.

But Lin thinks most of us would say that, in terms of their personal wellbeing, A’s life is better than B’s — because A’s life is actually happening . If we had to pick one, we would prefer to live A’s life than B’s.

While Lin’s new version of the thought experiment protects against the status quo and hedonistic biases, a hedonist might take issue with it in a different way: it exploits the so-called ‘freebie problem’.

If faced with two identical options, but one includes an extra bonus, we are likely to choose the extra bonus even if we’re not convinced it will make any difference; we pick it just in case .

So, in the context of Lin’s thought experiment, we say A has a better life not because we’re convinced, but because we’re hedging our bets that ‘living in reality’ has some kind of intrinsic value that increases A’s overall wellbeing. As Buscicchi puts it,

Most people will choose the life with the free bonus just in case it has intrinsic value, not necessarily because they think it does have intrinsic value.

What do you make of Nozick’s experience machine?

- Do you think the experience machine thought experiment is a successful argument against hedonism?

- Would you plug into a machine that offered to maximize your happiness?

- What do you make of the criticisms of Nozick’s thought experiment? Which do you find most convincing? Which do you find least persuasive?

- Does Eden Lin’s redesign of the thought experiment make it more powerful as an argument against hedonism?

- Where do you stand on hedonism? Does everything important in life ultimately come back to increasing pleasure / decreasing pain? What matters to you in life?

Learn more about Nozick, hedonism, and other philosophical approaches to the good life

I f you’re interested in learning more about Nozick and how other philosophers approach ethics and the good life, you might enjoy the following related reads:

- On Living Meaningfully in a Vast Universe: Robert Nozick

- Epicureanism Defined: Philosophy is a Form of Therapy

- The Greatest Happiness of the Greatest Number: What Bentham Really Meant

- Peter Singer On the Life You Can Save

- Iris Murdoch: ‘Unselfing’ is Crucial for Living a Good Life

- Ethics and Morality: the Best 10 Books to Read

- How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 17,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 17,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free):

About the author.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 17,000+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 17,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.

James Baldwin: Suffering Can Become a Force for Good

4 -MIN BREAK

The Stoics on What to Do When the World Feels Broken

7 -MIN BREAK

John Stuart Mill and Daniel Dennett on How to Critique ‘the Other Side’

5 -MIN BREAK

Laurie Ann Paul on How to Approach Transformative Decisions

9 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

Pleasure or Reality? The Experience Machine Debate

Conclusions often drawn from the famous thought experiment seem problematic..

Posted March 13, 2019

In his famous 1974 book Anarchy, State and Utopia , Robert Nozick presents his famous experience machine thought experiment. In this thought experiment, we are asked to imagine a scenario in which technology is so advanced that we can plug ourselves into a virtual reality machine for a very long time. When plugged in, we will experience life as very pleasant indeed. Before we plug in we can decide for ourselves what types of experiences we will have. Once the electrodes are connected to our head we will not know, of course, that we are plugged into the machine; we will believe that we really are receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature for writing the best novel of the century; that we really are extremely clever and attractive; that we really are painting like Picasso; or that we really are having a passionate love affair. (In fact, for all we know, we may be right now in an experience machine and not "really" reading this post from the screen in front of us.) We need not worry, in this thought experiment, about nutrition , safety or health; they are all taken care of. Nor are there any problems with family members that need care: We have no families, or they are fine, or they too will plug into the experience machine if we do. (I have slightly altered some of the details Nozick presents.)

Now the question arises: If there were such an opportunity for you, the reader, to plug in, would you? For life? For 20 years? For four years? Why would or wouldn't you?

Nozick believes that most people will choose not to plug into the machine. This may sound odd, since in the experience machine they are likely to experience life as far more pleasant than in real life. One way to interpret the refusal to plug into the machine is to suggest that people are not interested only, or mostly, in pleasure; it is not the only, or main, thing that people want in life. This may serve as an argument against what has come to be called hedonic theories of well-being , according to which people's well-being consists only of the balance of pleasure over pain. The refusal to plug into the machine suggests that we do not only want to feel subjective pleasure in our lives; we also want our lives to have some objective value . For example, we do not only want to be pleased by the thought that we wrote a good novel; we want to actually write a good novel. We want the achievement to be real, and we want to really be the ones making it.

The refusal to plug into the experience machine also has implications for discussions on meaning in life. Subjectivist theories of meaning in life hold that our sensation of meaningfulness or other subjective conditions is what makes life meaningful. Objectivist theories of meaning in life hold that attaining objective value in life is what makes life meaningful. Hybridist theories of meaning in life hold that both subjective and objective conditions have to be fulfilled in order that life be meaningful. The anticipated results of the experience machine thought experiment count against purely subjectivist views of meaning in life.

In his paper, "If You Like It, Does It Matter If It's Real?" Felipe de Brigard casts some doubt on both the anticipated results and on the way they are often interpreted. Brigard conducted experiments in which he presented to participants a somewhat different question than the one Nozick discussed: Brigard requested participants in the experiment to imagine that they already are connected to the experience machine, and then asked them whether they would like to disconnect . He presented three variations to the scenario: In the first, no information was given to participants about what they were in real life. In other words, participants were not told how real life would be for them if they unplugged from the machine. In the second variation, participants were told that in real life they were prisoners in a maximum security prison. In the third variation, participants were told that in real life they were multimillionaire artists living in Monaco.

Of those exposed to the first variation, only 54% said that they wanted to unplug. Thus, when told that they already are in the machine and that in order to live in reality they need to change the condition they are in, many did not prefer reality to the machine.

In the second variation, in which those unplugging would find themselves in a maximum security prison, only 13% preferred reality. This suggests that the pleasantness of life does, in fact, make a lot of difference to people thinking about the experience machine.

Somewhat surprisingly, in the third variation, in which moving to reality meant living the life of a multimillionaire artist in Monaco, 50% of the participants said that they would unplug. The difference between the second and third variations still shows that pleasantness of life does play an important role, but one would expect, if it played an important role, that the percentage of participants wishing to unplug would be higher in the third variation than in the first variation.

In his discussion, Brigard emphasizes what has come to be called in psychological research the status quo bias : People often show a preference to retain the conditions in which they find themselves rather than to change them; people like the status quo. For example, in an oft-mentioned experiment, Jack L. Knetsch gave rewards to two groups of undergraduate students. Each student in the first group got a mug bearing the university's logo, while each student in the second group got a chocolate bar. Then, all of the students were offered the option of trading the rewards they received with the students of the other group. But almost 90% of them preferred to keep the reward they had been given.

Brigard suggests that the many people's intuitive preference not to plug into the experience machine, in Nozick's version of the thought experiment, may well not have to do with the importance of retaining contact with reality or with the incorrectness of hedonism (or, it could be added, with the wrongness of subjectivism about meaning in life). It is likely, argues Brigard, that people's preference not to plug into the machine is mainly affected by the status quo bias.

Nozick's experience machine thought experiment, then, may prove less than it is often taken to. And it calls for much more discussion and deliberation. But this also brings up another issue that Brigard emphasizes at the end of his paper: Nozick and many of the philosophers who wrote about his thought experiment did not check empirically whether indeed most people do not wish to plug into the machine. They just predicted that this would be the case, without actually checking it. This is problematic, since the argument and much of the discussion following it relied on claims about how most people would react to this thought experiment without relying on any empirical data about how most people in fact choose. Many of those who wrote about the issue seem to have merely extrapolated from their own preferences to humanity at large. Some others seem to have extrapolated from their own preferences and from those of a few of their close friends to humanity at large. And yet some others also asked their philosophy students about their preferences, not always heeding the reasons the students raised. But these are surely not representative or reliable samples. There seems to be much more empirical and philosophical work to do on the topic before we draw conclusions about hedonism, subjectivism, and the nature of well-being and of meaning in life.

Robert Nozick Anarchy, State and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974), 42–45.

Felipe De Brigard, "If You Like It, Does It Matter If It’s Real?" Philosophical Psychology 23 (2010): 43–57.

Jack L. Knetsch, "The Endowment Effect and Evidence of Nonreversible Indifference Curves," American Economic Review 79 (1989): 1277–1284.

Iddo Landau, Ph.D. , is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Haifa. He has written extensively on the meaning of life and is the author of Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

9 Philosophical Thought Experiments You Should Know About

Thought experiments are imaginative devices that can help us better understand philosophy. They are a useful tool in education and entertainment and can be a great way to apply complex concepts to practical situations. Since philosophy looks at questions about life, you can make a thought experiment for nearly any philosophical idea. Learn about some of the most popular ones commonly used in philosophical discussions.

The Trolly Problem

The trolly problem is an ethical thought experiment. It first appeared in philosopher Philippa Foot's 1967 paper, "Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect." To start off the thought experiment, imagine you have control of a railway switch. There is an out-of-control trolley headed your way. Up ahead, the tracks of the railway branch into two different paths. On the first track, there is a group of five people; on the other track, there is one person. If you stand, watch, and do nothing, the trolley will head down the first track and kill five people. However, your control allows you to switch the path of the trolley. This way, it heads down track two and kills one person instead of five. The dilemma in this situation is whether or not to flip the switch. A utilitarian answer would be to flip the switch and kill one instead of five.

Selective Surgery

Imagine you are a doctor in the future, and an ill patient comes into your practice. The patient's symptoms lead you to the diagnosis that their heart is failing. Without treatment, the patient is going to die. In your office, the patient passes out. Fortunately, the patient can be saved with surgery that will give them a synthetic heart. The patient can live what you consider to be a good life after this surgery. However, as you are preparing the patient for surgery, a small card falls out of their pocket. The card says for religious reasons; the patient does not want any synthetic organs. Now you must make a decision. If you do not install the heart, the patient will die. However, if you install the heart, the patient will survive at the cost of you violating their wish to have no synthetic organs.

At the heart of this thought experiment is a choice between honoring someone's individual rights and honoring an outside moral code . This is a relevant topic today in bioethics. Philosophers who advocate strongly for personal rights would argue that doing the transplant is wrong. While philosopher John Locke wasn't exposed to this thought experiment, he is someone who expressed the importance of individual rights and consent. According to Locke, individual consent is a fundamental part of creating a political society. In his view, doing the transplant on an unconsenting individual would be wrong.

The Bad Father

A thought experiment that tests loyalty against ethical principles is the bad father. In the thought experiment, there is a son who holds honesty as the highest value. However, his father is not an honest man. One day, his son catches him stealing from a local farmer. In this situation, the son must make a choice. He could turn his father in for breaking the law and stealing. Or the son might feel an ethical obligation to keep silent about his father's crime. While you might find this question silly, ask yourself the implications this scenario has on a larger scale. Would it be better for children to stay loyal and protect their parents or better for them to alert the authorities when their parents stray from the law?

This thought experiment is a variation of the thought experiments proposed by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. He wrote a dialogue called Euthyphro, where Euthyphro takes his father, Socrates, to court. Euthypro argues taking his father to court is the right thing to do and the pious thing to do. However, Socrates disagrees with Euthypro about his impiety charges and gets into a debate with Euthypro about philosophical questions of universal justice, goodness, and piety. At the core of the philosophical thought experiment is the question of what happens when there is a conflict between our personal lives and the impersonal tenets we believe justice demands. The thought experiment brings old philosophical questions about justice to life.

Prisoners Dilemma

The prisoner's dilemma is a game that was created as a model of human cooperation. The experiment shows how people choose to cooperate or how they don't. The mathematician Albert Tucker is credited with formalizing the thought experiment. Today, a wide array of disciplines use the thought experiment, including philosophy, psychology, economics, and political theory.

For the experiment, imagine a cop arrests both Chris and Cindy for robbing a bank. They are in separate cells where they cannot communicate. Both want to be free and care more about their personal freedom than the freedom of their accomplice. A clever prosecutor will use their desire for freedom to his or her advantage. The prosecutor will tell each person separately that if they confess and their accomplice remains silent, they will drop all charges against them and their testimony to ensure their accomplice does serious time. If they both confess, the prosecutor will ensure they both get early parole. If they both remain silent, they will have to settle for sentences on firearms possession charges. The dilemma for the prisoners is that if they both confess, the outcome is worse than it would have been if they had both remained silent.

The prisoner's dilemma compares individual and group rationality. It shows there can be conflict between individual and collective interests. Conclusions drawn from the Prisoner's Dilemma have been used in modern-day philosophical discussions about arms races and the use of limited natural resources.

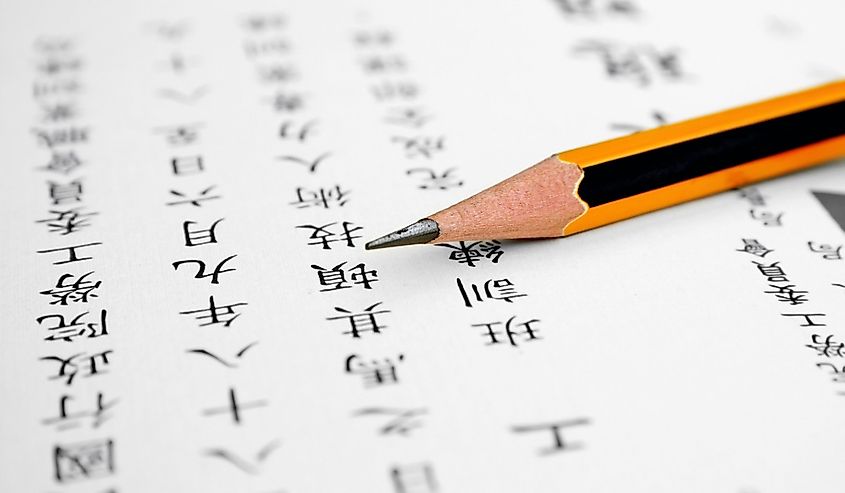

The Chinese Room

A thought experiment about artificial intelligence is the Chinese room, designed by philosopher John Searle. He asks us to imagine a situation where someone who only knows the English language is sitting alone in a room. They have instructions for changing rows of Chinese letters. Anyone outside the room would think the person inside the room understood Chinese since they would see them sorting through Chinese characters. However, this is not the case. The person inside the room just understands the instructions. Searle made this thought experiment to show that artificial intelligence cannot have a human-like mind. His thought experiment stresses that while there is understanding, there is not comprehension.

The Experience Machine

A thought experiment that will make you question the value behind experience, is Robert Nozick's Experience Machine. The experiment is from his book Anarchy State and Utopia . Imagine that there is a machine that will give you any experience you desire. You could enter the machine and have an experience that you were eating the world's best cookie or that you were an astronaut. While you are in the experience machine, you are floating in a tank with electrodes attached to your brain. The question here is if you should plug into this machine to preprogram your life experiences. While in the tank, you wouldn't know that you were in the tank, making the experience even more real. The thought experiment brings questions about the meaning of life. What is the purpose of life if we are plugging into a machine? Will plugging into a machine satisfy all of our desires?

The Ship of Theseus

The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that questions whether an object that has all of its components replaced or rearranged is in fact the original object. This paradox was recorded by Plutarch, Theseus, who asks if a ship that was fully restored and replaced completely, down to every single wooden part, was the same ship. Later, other philosophers expanded on this idea. Thomas Hobbes asked if the original planks of the first ship were entirely replaced and then the original planks were used to build another ship, if the second ship would be the original ship. The thought experiment asks questions about what the essence of an object is. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus attempted to solve this paradox. To do this, Heraclitus thought of a river that has water replenishing it. According to Heraclitus, this is the same river. However, Plutarch disagreed and claimed the nature of a river to scatter and then come together means you never step into the same river twice.

Original Position

Ever thought the system was unfair? The original position is a thought experiment centering around achieving a better form of justice. Developed by John Rawls, the thought experiment asks us to imagine that we are in a situation where we do not know our actual life. This way, we are behind what Rawls calls a veil of ignorance. This veil prevents us from knowing the political or economic system that we live under and the laws that are in place. From this position, we are then asked, with a group of other people behind the veil of ignorance, to look at a list of classic forms of justice. We must draw conclusions from different social and political philosophies. Then, we have to choose a system of justice that we believe would be best for everyone under this veil. This thought experiment calls us to question our beliefs about justice. It forces us to confront the flaws of our political and economic systems.

The Beetle in the Box

The Beetle in The Box thought experiment is also known as the Private Language Argument. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein developed the thought experiment to challenge the way we look at introspection and how it informs the language we use. The thought experiment starts by imagining a group of individuals, each holding a box. The boxes contain what each individual calls their beetle. Nobody can see into anyone else's box. Everyone describes their beetle to each other. However, each person only sees and knows their own beetle. According to Wittgenstein, the descriptions are unimportant. This is because, over time, the individuals would understand the word beetle as the thing in a person's box. While the thought experiment might sound silly, it makes the comparison that human minds are like a beetle. We can never know what is in another individual's mind.

Why Use Thought Experiments?

Thought experiments help us explore philosophical concepts in a more practical way. For example, the trolly problem forces us to confront how we would apply our ethics in a situation. The point of thought experiments isn't to arrive at a specific answer. Instead, thought experiments force us to reason through our ideas and give us insight into solving complex questions. When you come up with an answer to a thought experiment, why you arrived at your answer is just as important as the answer itself.

More in Society

Simone de Beauvoir's Perspective On Existential Feminism

10 Countries Where Women Far Outnumber Men

The 10 Oldest Cricket Grounds In The World

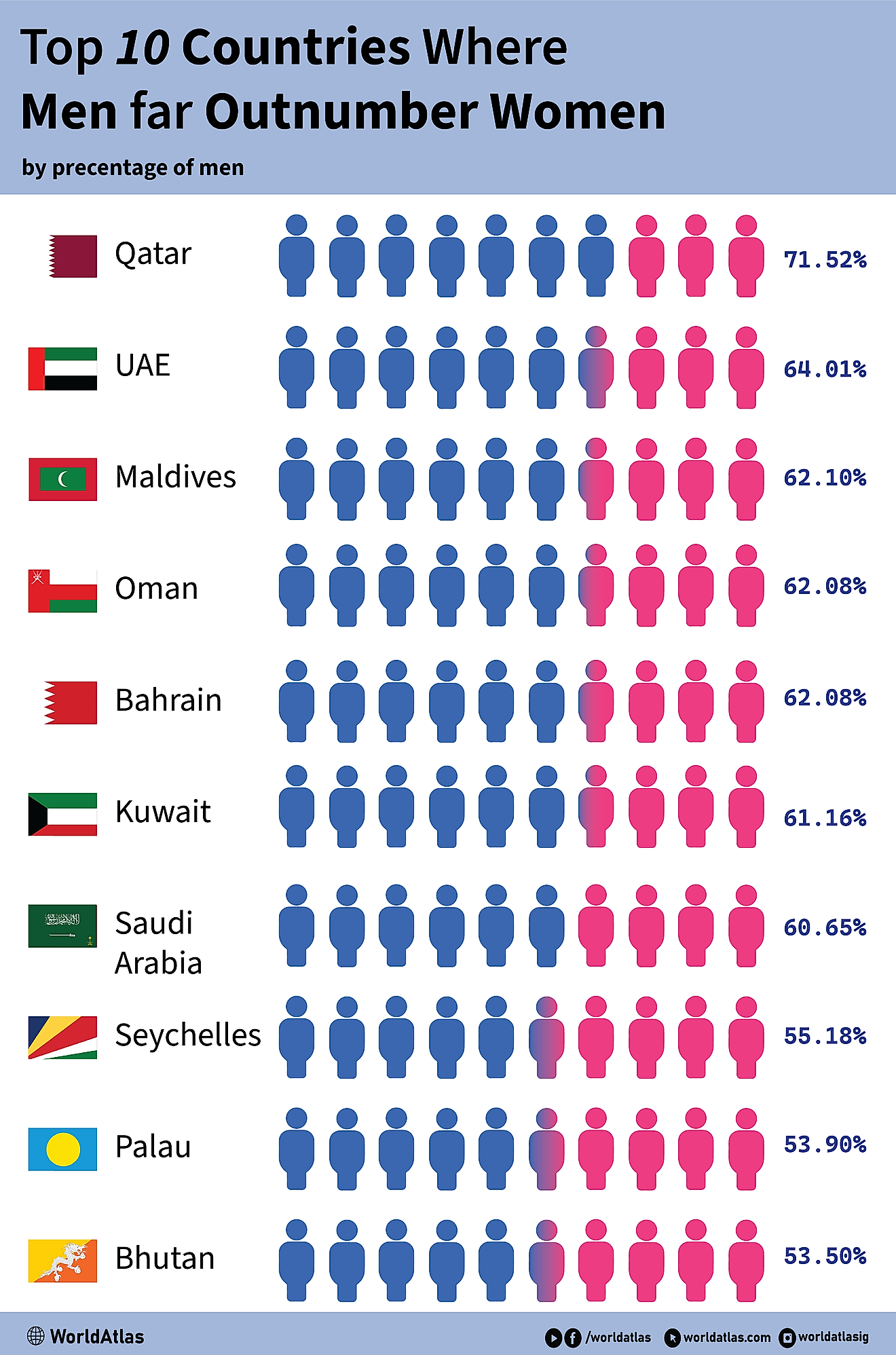

10 Countries Where Men Far Outnumber Women

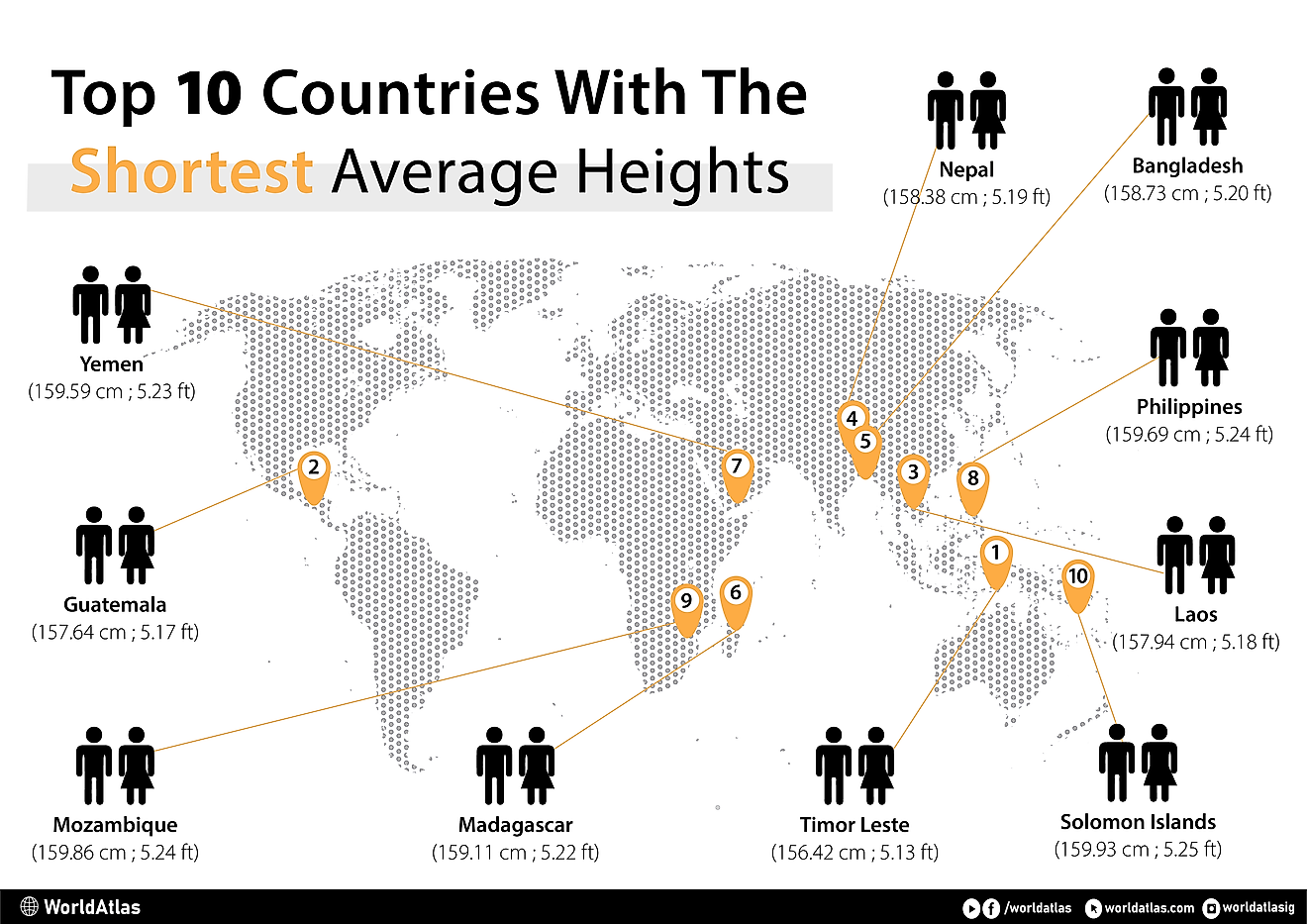

Countries with the Shortest Average Heights

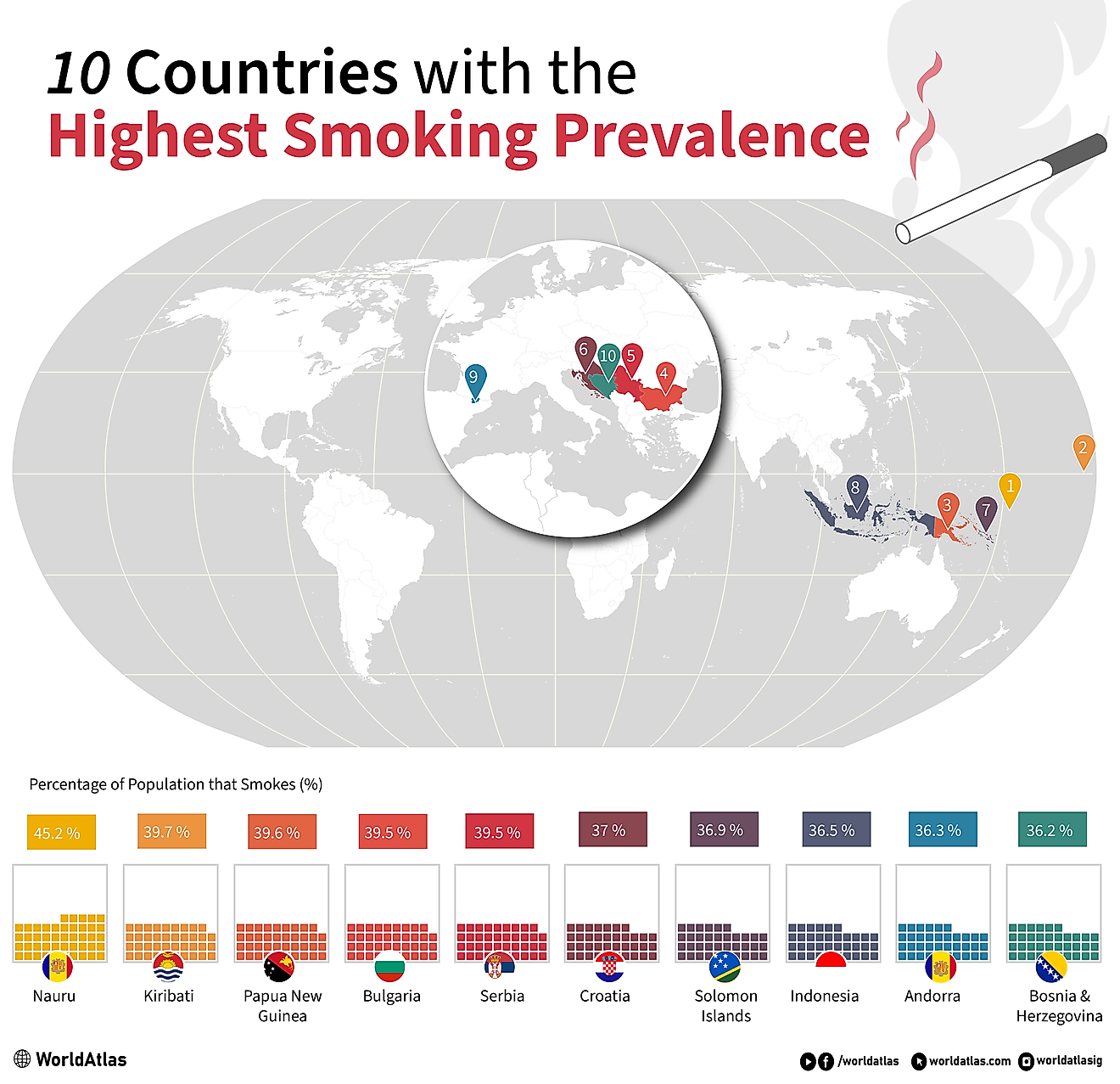

10 Countries Where People Smoke The Most

10 Creepy Urban Legends from Around the World

10 Urban Legends That Are Actually Based On Real Facts

- Course Calendar

University of Notre Dame

The Experience Machine

Pick a category.

- All Categories

- Digital Essay (31)

The Value of Pleasure

Is pleasure the only good thing there is? Some philosophers have thought so. Take anything you enjoy — going on vacation, eating a delicious pizza, reading a book. These are all things that cause pleasure , and that seems to be what makes them enjoyable. Reasoning in this way, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham concluded that pleasure is “the only good” and pain “without exception, the only evil”.

Thought Experiment

The Machine

To test this kind of view, the philosopher Robert Nozick developed the following thought experiment:

Suppose there was an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Super-duper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. While in the tank you won’t know that you’re there; you’ll think that it’s all actually happening.

Would you plug in? As Nozick asks, “What else can matter to us, other than how our lives feel from the inside?”

What Else Could Matter?

- Actual Accomplishment

- Personality & Character

- Deeper Reality

Nozick notes that we seem to value doing certain things, not just having the experience of doing them. “In the case of certain experiences,” he says, “it is only because first we want to do the actions that we want the experiences of doing them or thinking we’ve done them.”

Suppose you solved a puzzle in your dream, then woke up to realize that you hadn’t actually completed it. It seems like some part of your accomplishment would go missing. You didn’t really do what you were proud of having “accomplished” in your dream. You didn’t actually do anything at all!

“We want to be a certain way,” Nozick says, “to be a certain sort of person” with a distinctive personality and moral character — but plugging into the machine seems to preclude this. As Nozick puts it:

“Someone floating in a tank is an indeterminate blob. There is no answer to the question of what a person is like who has been long in the tank. Is he courageous, kind, intelligent, witty, loving? It’s not merely that it’s difficult to tell; there’s no way he is. Plugging into the machine is a kind of suicide.”

If we plug in, we’re limited to a human-created reality. And while this might not be terrible for a few hours (we often waste this much time on our phones, or immersed in a television show), we value living in a world that wasn’t created by beings like ourselves, with limited imaginations, time, and creative energy.

“Plugging into an experience machine limits us to a world no deeper or more important than that which people can construct. There is no actual contact with any deeper reality; but many persons desire to leave themselves open to such contact, and to a plumbing of deeper significance. This clarifies the intensity of the conflict over psychoactive drugs, which some view as mere local experience machines, and others view as avenues to a deeper reality; what some view as equivalent to surrender to the experience machine, others view as following one of the reasons not to surrender!”

What Does the Thought Experiment Show?

In philosophy, we often use thought experiments like Nozick’s example of the Experience Machine to help us reflect on more abstract questions. In this case, considering what you would do if you had the option to plug into the Experience Machine can lead you to more general insights about what matters to you in life, what ingredients are needed in a good life, and more.

Nozick’s take on the thought experiment is that it shows that we care about more than simply having certain kinds of experiences. And he thinks parallel thought experiments can help us learn even more about what we value:

- The Transformation Machine would transform you into any kind of person you’d like to be.

- The Result Machine would produce whatever results the actions you experience yourself doing while in the Experience Machine would have if you had actually done them.

Would you be any more willing to plug into the Experience Machine if you could also use one (or both) of these machines beforehand? (For example, you could use the Transformation Machine to transform yourself into a highly talented doctor, use the Result Machine to produce a cure for the common cold, and then use the Experience Machine to give yourself the experience of discovering the cure through your own research. Would you find as much value in this as you would in actually training to become a doctor and discovering the cure through your own work?)

Reflecting on questions like these, Nozick thinks, reveals that our most central desires — to have certain experiences, to be a certain type of person, to bring about certain outcomes — only have force in the context of the actual lives we are living . As he puts it, “ Perhaps what we desire is to live ourselves, in contact with reality. And this, machines cannot do for us. “

For this class, Scheffler’s concept of being homeless in time is one of the most important parts of this chapter. The notion is similar to temporal mobility in the sense that we cannot control our movement. However, temporal mobility refers to individuals occupying space. It is true that we cannot control our movement at all times, but we do have some influence on our surroundings at certain points in life. For instance, one can control whether they attend class one day or not. In that sense, one expresses ownership over the possibility of occupying a classroom. Now, Scheffler is consider the ownership of time. According to him, it is not possible to express ownership over time, even in an insignificant amount. It is a dimension humans simply cannot express ownership over. Time is a constantly moving force and individuals have no control over its direction or magnitude. In this way, humans have no ability to occupy time itself.

Temporal mobility refers to the notion that humans cannot control our movement through time. While we may be able to influence our movement or actions in particular moments, we have very little influence on the broad scope of our entire life. Regardless of our wishes, time is always moving forward and we must adapt to it. While Scheffler notes that this is often taken for granted, it is a frustrating fact of life. As individuals (supposedly with free will), we expect to have full dominion over our lives; yet, we cannot master time and its influence over us. According to Scheffler, these circumstances emphasize the importance of tradition. A particular practice repeated at regular intervals enables an individual to have ownership over at least some aspects of one’s life.

Normativity refers to an evaluative statement as to whether something is desirable. It is important to distinguish normativity from positivism, which postulates one should only make claims based on empirical evidence. A positive statement makes a claim as to how things are, whereas a normative statement makes a claim to how things should be. A normative statement seeks to attach a belief or expectation to already established facts. To understand this distinction, refer to the following example:

Positive Statement: “Jake’s dog is a German Shepherd.”

Normative Statement: “German Shepherds are the best breed of dogs.”

Scheffler provides a definition of tradition that provides insight into his understanding of the term and its significance in human culture. Read it below as context for the rest of the digital essay. This is what Scheffler means by “tradition”:

Two points of clarification are in order. First, in one broad and standard sense of the term, a tradition is a set of beliefs, customs, teachings, values, practices, and procedures that is transmitted from generation to generation. However, a tradition need not incorporate items of all the kinds just mentioned. In this essay, I am interested in those traditions that are seen by people as providing them with reasons for action, and so I will limit myself to traditions that include norms of practice and behavior.

Second, there is a looser sense of the term in which a tradition need not extend over multiple generations. A family or a group of friends may establish a “tradition,” for example, of celebrating special occasions by going to a certain restaurant, without any thought that subsequent generations will do the same thing. Even a single individual may be described as having established certain traditions, in this extended sense of the term. [B]ut my primary interest is in the more standard cases in which traditions are understood to involve multiple people and to extend over generations.

The transition from personal salvation to universal redemption marks the transition of humanity from pursuing evil to seeking the good. Once an individual realizes that satisfying one’s pleasures and self-interest is not worthy, as it provides no meaning to life, one will instead actively look for goodness as a higher source of meaning. This leads one to pursuing God and developing a close relationship with God, actualized through acts of justice and mercy in pursuit of a better world.

One should note also that this redemption is universal. Heschel draws a distinction between his argument and personal salvation, arguing that simply pursuing the latter is another form of self-interest. Rather, the way to truly prevent suffering is committing oneself to salvation for the entire world, which he terms as universal redemption. It is through this method that humanity can become closer to God and end evil in the world.

Here, Heschel refers to the prophets of the Hebrew Bible who frequently criticized the Israelites for various offenses against God, such as worshipping false gods. An interesting notion that Heschel introduces here and develops in the subsequent paragraphs is a distinction between history and redemption. For him, history refers to human activities, ripe with the injustices and suffering associated with the pursuit of human self-interest. This is separate from the redemption, which refers to a state of affairs beyond history that involves concepts of salvation, the kingship of God, and other faith-based ideas. Heschel uses this distinction to separate the evils of our world from the goodness of God, counteracting the illusion of evil he mentioned earlier in the excerpt.

For Heschel, “alien thoughts” are ideas that enter one’s mind that dissuade one from pursuing righteous actions. He believes that even if an individual pursues good acts and remains faithful to God, foreign concepts will enter one’s thoughts with the mission to drive them away from God and goodness. This exacerbates the tension between God and humanity because it is rooted in human self-interest.

One of Heschel’s concerns is that God’s will and human nature are inherently opposed to one another. He believes that humans are naturally selfish and pursue ends that benefit themselves, even at the expense of others, which inevitably leads to situations where one will sacrifice piety or adherence to God’s will for some other goal. The desire to pursue self-interest introduces deceitful thoughts that drive one away from God and a life of holiness. Heschel also believes that self-interest contributes to suffering in the world. To prevent evil, humans must work towards rejecting their pursuit of self-interest through activities like faith and following God’s will.

Heschel is also concerned with how good and evil can often be confused for one another. What appears as holy and good may actually be evil in disguise around the illusion of self-interest. An example is worshipping a false idol. One may believe that their act is holy and upholds God’s will, but according to Heschel, the act only reinforces the evil and sinful nature of the world.

Here, Cohen is describing humanity grappling with the concept of absolute evil once it has entered reality. He argues that prior to the tremendum, the notion of absolute evil was simply a concept that existed in the mind that was thought to never exist in the real world. This enabled individuals to justify “relative evils” that were comparably smaller to the absolute evil that existed only in human consciousness. However, the Holocaust demonstrated that absolute evil, suffering and horror exercised without rationality or moral consideration, is certainly possible in this world. For Cohen, this means that there are no more excuses for the relative evil because the absolute evil is as real as it.

Cohen uses the term “vector” similar to mathematicians and physicians, in that it refers to something that has both magnitude and direction. When he says reason has a “moral vector,” he is suggesting that rationality is accompanied by moral considerations that drive the process of reasoning. Cohen believes that moral principles and rationality are intertwined, in that morality is rational and rationality is moral. As a result, any rational conclusion must also be morally acceptable. For this reason, Cohen notes that an evil like the Holocaust cannot be rational because it is not moral in any sense. Likewise, it cannot be moral because it is not rational.

What do you think of Cohen’s intertwining of reason and morality? Do you think that rationality has a moral vector? Should reason and morality be inherently connected or separate? Can someone reason something that is not moral?

Tremendum typically means “awefulness, terror, dread” and other similar feelings. Here, it is Cohen’s term for the Holocaust. He uses this term because he believes there is no evil equivalent to the Holocaust, so using the terms typically used to describe mass suffering is not an adequate description. He adopts the word tremendum because he believes it best captures the horrible realities of the Holocaust compared to other available terms, although it still ultimately falls short because humanity simply cannot comprehend the true extent of the events that took place during the Holocaust.

Mipnei Hataeinu is Hebrew for “because of our own sins” and refers to the concept that humanity’s suffering is brought about by its sins. In other words, destruction and pain are punishments for sinful behavior. The interpretation would suggest that humanity deserves this chastising, as indicated by Isaiah 59:12: “For our transgressions against You are many, and our sins have testified against us, for our transgressions are with us, and our iniquities – we know them.” Mipnei Hataeinu reveals that punishment is justified because it is a response to humanity’s sins, similar to how a parent might discipline a child.

However, recall that such an explanation for the Holocaust does not suffice. There is no rational explanation for anything committed by the Jews that would warrant such a devastating slaughter and genocide. For this reason, Berkovits rejects this view and instead relies on the free will argument to explain why God would permit the Holocaust to occur.

Hester Panim is a Hebrew phrase that means “hiding face” and is used commonly in Jewish biblical interpretation. It refers to the concept of God literally hiding Himself from the suffering of humanity. As the Torah (the Hebrew Bible) demonstrates, there are many times that God rescues the Israelites from devastation, whether it is being brought against the Israelites or they committed the evil themselves. Hester Panim is usually interpreted as those times that God does not save the Israelites. It is interpreted as a punishment for not following the covenant or breaking God’s laws. Some scholars take a less vindictive approach, believing that God hiding Himself is an act of love and compassion because He cannot bear to watch His people suffer, similar to how a father does not want to watch his son get hurt.

Berkovits uses an entirely different interpretation of Hester Panim, drawing from the Jewish concept of nahama d’kissufa (Hebrew for “bread of shame”). Nahama d’kissufa refers to the notion that greater satisfaction derives from being deserving of a reward than simply receiving it as a gift. For example, giving yourself a dessert as a reward for doing well on an exam is more meaningful than simply eating the dessert. Berkovits argues that God granted humanity free will to make our achievements more significant and worthwhile. As a result, God must distance himself from humanity to enable humans to exercise that free will to the greatest extent. This inevitably allows evil to occur in the world, as any interference by God to prevent evil would undermine humanity’s free will.

Here, Marx argues that in practicing religion, man becomes alien from his own life. How might other philosophers, such as Aquinas or Nietzsche, agree or disagree with this claim?

Key Terms: Objectification and Alienation: Marx defines a sort of two-pronged process of objectification and alienation. He defines objectification as the process of labor becoming a commodity in itself– and alienation refers to that commodity becoming something that is separate from the laborer.

Key Point: Stoicism is an ancient philosophy known for its emphasis on wisdom, virtue, and harmony with divine reason. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/stoicism/

The Grand Inquisitor was the lead official of the Inquisition, appointed by the Church. During the Inquisition, a time infamous for the torture and execution of heretics, the Inquisitor was a powerful authority figure in society. Note that Dostoevsky does not portray the Inquisitor as evil, but rather as a character whose aims are understandable.

A heretic is a person who has been baptized as a Christian but doubts or denies established religious principles. In the sixteenth century, the time when Christ is reborn on Earth in this story, heretics were executed or even burned at the stake during the Inquisition.

Key Term: remote effects refer to more distant and difficult-to-anticipate consequences that someone’s actions may have, ex. someone’s decision to take public transportation to save on gas costs may unwittingly cost a car salesman their job.

Ernest Partridge was an environmental philosopher who wrote extensively on duty to future generations. You can find more of his work on his website, The Online Gadfly, a title with a clever reference to Socrates. This website, according to his obituary, is also a virtual monument to continue on his legacy and work into the future.

Taylor is a Canadian philosopher and professor emeritus at McGill University known especially for his work related to political and historical philosophy. Taylor has critiqued Liberalism, naturalism, and secularism throughout his long career. He will be 90 in November of 2021.

Here Kavka is accounting for population growth or decline.

Otherwise known as the Lockean Proviso, this idea is that a person has a right to the property that they put work into as long as in claiming this property there is enough of that quality resource left for others. In other words, no one is worse off with that resource claimed.

An English Enlightenment philosopher, John Locke is known for his political philosophy and work on epistemology and metaphysics. Kavka is drawing from his writing in section 4 of the second treatise in Locke’s Two Treatises of Government.

There’s a distinction here…. not nec strongest possible reason, all things being equal, no one is required to have millions of kids.

Remember Kavka’s previous argument about contingency: if it is certain that there will be no future people, then they have no moral weight.

The “contingency” of people is the last concept that Kavka grounds his discussion on. The idea is that we cannot be certain as to whether future people will exist at all; in some respects, we can only assume that they will, but there’s always a chance that they won’t.

The term “temporal location” refers to a thing’s existence in a particular time. This concept is the basis of Kavka’s first point in the following section.

Kavka calls this “the more modest conditional conclusion” because it leaves open the possibility for further discussion. If someone does not accept the initial premise that “we are obligated to make sacrifices for needy strangers” then they do not have to accept the conclusion that they must sacrifice for future generations.

A telling title to his essay, “futurity” refers to all future time and events. Kavka will wrestle with the moral challenges that arise when we consider the obligations futurity imposes on us in the present.

When Ivan says “I hasten to return my ticket,” he is referring to the possibility that he might be rewarded in the afterlife after suffering in this world. Ivan cannot rationalize any argument that might justify unnecessary suffering and refuses to participate in such a system. This is where Ivan rejects the harmony, participating in what his brother deems rebellion.

When Dostoyevsky uses the term harmony, he refers to the belief that one’s suffering in this world is worthwhile because it will be rewarded in the afterlife. Ivan is adamantly against this idea, explaining that future benefit does not justify current suffering. If someone is sent to Heaven after having suffered immensely, it does not erase that the suffering happened in the first place. For Ivan, no future benefit can justify the current injustice of suffering.

Here, Ivan is referencing Jesus giving the Great Commandment. The verses (Matthew 22:35-40) of the passage are below.

And one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question, to test him. “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the law?” And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets.

Even after receiving a wage that is less than the value they have contributed to production, the proletariat must give much of their earnings to other members of the bourgeoisie in order to survive. For Marx, capitalism places the proletariat in constant subjugation to the bourgeoisie.

Marx argues that capitalism provides unjust wages to the proletariat. Think about the process of capitalism: a business owner provides resources, a worker produces a product, the worker receives a wage for that labor, and the business owner sells the product. For the business owner to have a profit, the selling price must be higher than the wage earned by the worker. Marx contends that this process devalues the worker’s wage, and therefore their humanity. This suggests that capitalism, as a system, dehumanizes and oppresses the proletariat. For capitalism to survive, and profit to exist, the proletariat must be devalued.

Just as the proletariat are reliant on labor to survive, they become an object to the system. Similar to the products they produce, the proletariat are bought and sold by the bourgeoisie to benefit the capitalist system.

Here, Marx argues that in capitalism, workers are only valuable to society if they are productive. When he says “labour increases capital”, he means that the proletariat’s work must contribute to the wealth of the bourgeoisie for the proletariat to survive. If a worker is unproductive, they will be deprived of a wage and will lack the resources to live. This is a key part of Marx’s criticism, that survival is dependent on productivity.

This is one of the most famous phrases from The Communist Manifesto . Here, Marx argues that the bourgeoisie, driven by a constant need to expand their markets (and therefore wealth) are forced to fundamentally change society. The simple, laboring feudal lifestyle is replaced with industrial machines creating elaborate products with little effort. Thus, capitalist relations of production tend to spread geographically, as well as into more and more areas of human life.

A key part of Marx’s theory is that common laborers have been reduced to wage earners and that this is bad for human well-being. For Marx, work is an essential part of human identity. It is a way of human flourishing, because your work is an extension of who you are. However, Marx contends that industrialization has led to the commodification of work — a worker is the kind of thing that a price is put on, that bourgeosie trade. Instead of doing your job simply for the sake of it, the proletariat are forced to work only to survive. And even then, the work is more and more disconnected from human life – it is reduced down to simple tasks alongside machines that have further dehumanized the work experience. When Marx says these individuals have become “paid wage labourers”, he is criticizing capitalism’s deteriorating effect on the value of work for individuals.

Aristotle also used knife imagery to talk about the purpose of human beings. For him, a good knife is one that fulfills its purpose (a sharp knife!), and a good human is someone who lives as a rational animal to the best of their ability. As you continue reading through Sartre, see if you can pick up on the difference in Sartre’s use of the knife. How does he relate the knife image to human beings? Why does he think humans are different from knives?

It is precisely the opinions that are most disagreeable to us that we have to do the most to preserve. They are the most in danger of being legally or socially suppressed, and society would be worse off if they were suppressed because our beliefs would become lively and understood.

Because the common consensus is one-sided, we shouldn’t be upset when the minority opinion is biased and one-sided too. What’s more, one-sided people are usually more emphatic and passionate about their belief, so Mill says it’s actually a good thing if the disagreement is expressed in a one-sided way.

Open-mindedness is difficult for people. Usually, we act and think as if what we do is the only way to do things.

Suspending judgment, is refraining from either believing or disbelieving in something. (Suspending judgment on whether God exists is agnosticism.) Mill thinks we sometimes ought to suspend and admit that we don’t have enough information to make a call. Better to admit your ignorance than to hold an opinion without knowing why you hold it.

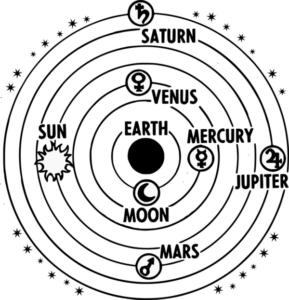

A geocentric model of the solar system has earth at the center; a heliocentric model has the sun at the center. Phlogiston was believed to be a chemical substance playing some of the roles that we now know oxygen plays. Scientists now agree there is no such substance as phlogiston.

To be a ‘rational being’ just means that we humans can reason , we can think critically, imagine possible futures and choose between them, and make arguments. Because we have this unique strength, Mill believes we should use it as much as possible. In the next paragraph, Mill will discuss what it means to use our reason.

Mill is criticizing here people who consider blind faith a virtue, who believe things simply because their god or another authority figure told them they are true, and who cannot give good arguments for why they believe what they believe. This is no way for a rational person to live, he says.

For a defense of blind faith in certain circumstances, see our lesson on Kierkegaard.